People have commented about what kind of entertainment is appropriate - if appropriate is even the word - for this odd time. Do we embrace it, Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year, or Camus, or turn to escapism? Conventional wisdom has it that screwball was so popular during the Depression because it didn't reflect actual living conditions. On the other hand, during the polio epidemic, there was a brief vogue for the iron lung as a story element. Noir mirrors a specific postwar unease, which overlaps Cold War nuclear anxiety. Kiss Me Deadly or Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Godzilla is the atomic metaphor writ large and reptilian.

I seem to be in retreat, myself, falling back on comfort food. Instead of post-apocalyptic, I set sail instead with Dorothy Sayers and her Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries.

Now, right up front, let's admit some of these are pretty lightweight. Whose Body?, the debut, is contrived and gimmicky. Clouds of Witness is stronger, mostly because the stakes are higher. Unnatural Death seems labored, to me, and basically unconvincing - although it introduces the estimable Miss Climpson. I don't think Sayers (and Wimsey) really hit their stride until The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, and I think also this is because Bellona is to some degree about the effects of the Great War on Wimsey and his generation.

Sayers wrote novels of manners; contrivance is less important than character. Wimsey is himself nowhere near the foppish dilettante he affects to present - this is a Scarlet Pimpernel device. (You can easily imagine Leslie Howard in the part, deceptively languid.) Wimsey was a major in the Rifles, and was invalided out. There's a scary moment in Whose Body? when he imagines hearing German sappers digging below, and Bunter has to talk him down and put him to bed. The relationship between Wimsey and Bunter is the spine of the stories.

The other thing we have to acknowledge, which for some readers could be a deal-breaker, is that the language of the period singes the present-day ear. You remember that the books started in the 1920's, so astonishingly, they're almost a hundred years old. This isn't to apologize for Sayers' vocabulary, or rather, the accuracy with which she reports the vocabulary of the British class structure. She doesn't necessarily share their prejudices, but you doubt she's inoculated against them. Then again, Wimsey seems to be playing a part, 'Lord Peter' a kind of self-parody, so how much of this is affectation? It's hard to distinguish between the narrative conventions and Sayers' personal feelings. She herself was apparently quite astonished when somebody suggested anti-Semitic tropes in her work.

The three strongest books are the late-runners, Murder Must Advertise, The Nine Tailors, and Gaudy Night. Murder Must Advertise because it's so effectively mannered - as a novel of manners ought - and because Sayers makes fun of her own successful career as an advertising copywriter. The Nine Tailors because the mystery is so elegant, the bell-ringing so exact, and the surrounding fen country so beautifully evoked. Gaudy Night is an outlier, granted, because it's of course Harriet's book, not Peter's, but the atmospherics are extraordinary, overheated and claustrophobic.

I also recommend The Documents in the Case, which is a standalone, without Wimsey, but the forensics reveal at the end is worth it all by itself.

The other thing about the language in the books, though, is how much it represents a world of the past. Not the late Victorian era of Holmes, but a time we think we can almost reach, from our own experience. Not that many degrees of separation. The period between the wars could be our parents, or theirs. You remember hearing an expression, as a kid, that made no sense whatsoever, because the context belonged to a previous generation. "Clean your plate," my grandmother might say, "think of those starving children in Belgium." Her reference is the First World War.

My personal favorite in the novels is widdershins, which means counter-clockwise, but Wimsey uses it in a particular way, "We do no harm in going widdershins, it's not a church." This puzzled me, until I unearthed a more sinister definition, invoking malign spirits. Originally, however, it seems simply to describe a cowlick or a case of bad hair. And there's the charm.

Showing posts with label Lord Peter Wimsey. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Lord Peter Wimsey. Show all posts

08 July 2020

09 January 2016

Of Lords and Eggs

by Unknown

Mystery short stories offer

us many pleasures, including the opportunity to enjoy,

briefly, the company of protagonists who might drive us crazy if we

tried to stick with them through an entire novel. I was reminded of this

truth recently when I reread a Dorothy L. Sayers story featuring

Montague Egg, a traveling salesman who deals in wines and spirits. Most

Sayers mysteries, of course, center on another protagonist, Lord Peter

Wimsey. As almost all mystery readers know, Lord Peter is highly

intelligent, unusually observant, and adept at figuring out how

scattered scraps of information come together to point to a conclusion.

Montague Egg fits that description, too. Both characters are engaging

and articulate, both have exemplary manners, and both sprinkle their

statements with lively quotations. More important, both Lord Peter and

Montague Egg abide by codes of honor, and both are devoted to the cause

of justice, to identifying the guilty and exonerating the innocent. And

Sayers evidently found both protagonists charming: She kept returning to

them for years, writing twenty-one short stories about Lord Peter,

eleven about Montague Egg.

But while Sayers also wrote eleven novels about Lord Peter,

she didn't write a single one about Montague Egg. I don't know if she

ever explained why she wrote only short stories about him--I checked two

biographies and didn't find anything, but there might be an explanation

somewhere. In any case, it's tempting to speculate about what her

reasons might have been.She

might have thought Egg lacks the depth of character needed in the

protagonist of a novel. That's true enough, but she could always have

developed his character further, given him more backstory. She did that

with Lord Peter, who's a far more complex, tormented soul in Gaudy Night and Busman's Honeymoon than he is in Whose Body?

Or perhaps she thought all the little quirks that make Montague Egg

such an amusing, distinctive short story protagonist would make him hard

to take if his adventures were stretched out into a novel. Yes, Lord

Peter has his little quirks, too, but I think his are qualitatively

different. For example, while Lord peter tends to quote works of English

literature in delightfully surprising contexts, Montague Egg sticks to

quoting maxims from the fictional Salesman's Handbook, such as

"Whether you're wrong or whether you're right, it's always better to be

polite." Three or four of these common-sense rhymes add humor to a quick

short story. Dozens of them might leave readers wincing long before a

novel ends.

I did plenty of wincing when I decided, not long ago, to read Anita Loos' Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

(not a mystery, but protagonist Lorelei Lee does go on trial for

shooting Mr. Jennings, so I figure I can sneak it in as an example). For

the first thirty pages or so, I relished it, laughing out loud at

Lorelei's uninhibited voice, at the absurd situations, at the appalling

but flat-out funny inversions of anything resembling real values. Before

long, however, I was flipping to the back of this short book to see how

many more pages I had to read before I could declare myself done.

Lorelei's voice, which had been so entertaining at first, had started to

get on my nerves, and her delusions and her shallowness were becoming

hard to take. I couldn't understand why this book had been so wildly

popular until I found out it had originally been a series of short

stories in Harper's Bazaar. Well, sure. A small dose of Lorelei

once in a while can be enjoyable, but spending hours with her is like

getting stuck talking to the most self-centered, superficial guest at a

party. If you ever decide to read Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, I recommend reading it one chapter at a time, and taking at least a week off in between.

There could be all sorts of reasons that a protagonist might be right for short stories but wrong for novels. I wrote a series of stories (for Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine) about dim-witted Lieutenant Walt Johnson and overly modest Sergeant Gordon Bolt. Everyone--including Bolt--sees Walt as a genius who cracks case after difficult case. In fact, Walt consistently misunderstands all the evidence, and it's Bolt who solves the cases by reading deep meanings into Walt's clueless remarks. A number of readers urged me to write a novel about this detective team. (And yes, you're right--most of these readers are members of my immediate family. They still count as readers.)

Despite my fondness for Walt and Bolt, though, I never even considered writing a novel about them. I think they're two of the most likable, amusing characters I've ever created. But Walt is too dense, too anxious, and too cowardly to sustain a novel. How long can readers be expected to put up with a detective who's always confused but never scrapes up the courage to admit it, no matter how guilty he feels about taking credit for Bolt's deductions? And while I find Bolt's self-effacing admiration for Walt sweet and endearing, I think readers would get fed up with his blindness before reaching the end of Chapter Two.

I think these two are amusing short-story characters precisely because they're locked into patterns of foolish behavior. As Henri Bergson says in Laughter, repetition is often a fundamental element in comedy. But this sort of comedy would, I think, get frustrating in a novel. Readers expect the protagonists in novels to learn, to change, to grow. Walt and Bolt can't learn, change, or grow without betraying the premise for the series. So I confined them to twelve short stories, spread out between 1988 and 2014. In the story that completed the dozen, I brought the series to an end, doing my best to orchestrate a finale that would leave both characters and readers happy--a promotion to an administrative job for Walt, so he can stop pretending he's capable of detecting anything, and a long-awaited wedding and an adventure-filled retirement for Bolt. I truly love these characters. But I'd never trust them with a novel.

Other short-story protagonists, though, do have what it takes to be protagonists in novels, too. Lord Peter Wimsey is one example--in fact, most readers would probably agree that, delightful as most of the stories about him are, the novels are even better. Sherlock Holmes is another example--four novels, fifty-six short stories, and I think it's fair to say he shines in both genres. I considered one of my own short-story protagonists so promising that I decided to build a novel around her. Before I could do that, though, I had to make some major changes in her character.

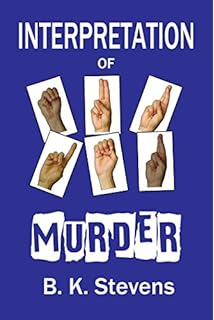

American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi first appeared in a December, 2010 Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine story, now republished as a Kindle story called "Silent Witness." Positive responses to the story--including a Derringer from the Short Mystery Fiction Society--encouraged me to think I might be able to do more with the character. It also helped that one of my daughters is an ASL interpreter who can scrutinize drafts and provide insights into deaf culture and the ethical dilemmas interpreters face. And I like Jane. She's smart, she's observant, she has acute insights into human nature, and she has a strong sense of right and wrong. In "Silent Witness," when she interprets at the trial of a deaf man accused of murdering his employer, she wants the truth to come out. She definitely doesn't want to see an innocent man go to prison.

But

the Jane Ciardi of "Silent Witness" is mostly passive. She's sharp

enough to figure out the truth and to realize what she should do, but

she lacks the courage to follow through. Her final action in the story

is to fail to act, to sit when she should stand, to convince herself

justice will probably be done even if she remains silent. I think all

that makes Jane an interesting, believable protagonist in a short story

that raises questions it doesn't quite answer.

But

the Jane Ciardi of "Silent Witness" is mostly passive. She's sharp

enough to figure out the truth and to realize what she should do, but

she lacks the courage to follow through. Her final action in the story

is to fail to act, to sit when she should stand, to convince herself

justice will probably be done even if she remains silent. I think all

that makes Jane an interesting, believable protagonist in a short story

that raises questions it doesn't quite answer.

I don't think it's enough to make her a fully satisfying protagonist in a novel--at least, not in a traditional mystery novel. In what's often called a literary novel, the Jane of "Silent Witness" might do fine--another protagonist paralyzed by doubt, agonizing endlessly about right and wrong but never taking decisive action. The protagonists of traditional mysteries should be made of sterner stuff. So in Interpretation of Murder, I made Jane regret and learn from the mistakes she'd made in "Silent Witness." We find out she did her best to correct them, even though it hurt her professionally. And when she's drawn into another murder case, she works actively to uncover the truth, she comes up with inventive ways of gathering evidence, and she speaks out about what she's discovered even when situations get dangerous. I can't be objective about Jane--others will have to decide if these changes were enough to make her an effective protagonist for Interpretation of Murder. But I'm pretty sure mystery readers would find the Jane of "Silent Witness" a disappointing companion if they had to read an entire novel about her.

Have you encountered mystery characters who are effective protagonists in short stories but not in novels--or, perhaps, in novels but not in short stories? If you're a writer, have you decided some of your protagonists work well in one genre but not in the other? If you've used the same protagonist in both stories and novels, have you had to make adjustments? I'd love to hear your comments.

There could be all sorts of reasons that a protagonist might be right for short stories but wrong for novels. I wrote a series of stories (for Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine) about dim-witted Lieutenant Walt Johnson and overly modest Sergeant Gordon Bolt. Everyone--including Bolt--sees Walt as a genius who cracks case after difficult case. In fact, Walt consistently misunderstands all the evidence, and it's Bolt who solves the cases by reading deep meanings into Walt's clueless remarks. A number of readers urged me to write a novel about this detective team. (And yes, you're right--most of these readers are members of my immediate family. They still count as readers.)

Despite my fondness for Walt and Bolt, though, I never even considered writing a novel about them. I think they're two of the most likable, amusing characters I've ever created. But Walt is too dense, too anxious, and too cowardly to sustain a novel. How long can readers be expected to put up with a detective who's always confused but never scrapes up the courage to admit it, no matter how guilty he feels about taking credit for Bolt's deductions? And while I find Bolt's self-effacing admiration for Walt sweet and endearing, I think readers would get fed up with his blindness before reaching the end of Chapter Two.

I think these two are amusing short-story characters precisely because they're locked into patterns of foolish behavior. As Henri Bergson says in Laughter, repetition is often a fundamental element in comedy. But this sort of comedy would, I think, get frustrating in a novel. Readers expect the protagonists in novels to learn, to change, to grow. Walt and Bolt can't learn, change, or grow without betraying the premise for the series. So I confined them to twelve short stories, spread out between 1988 and 2014. In the story that completed the dozen, I brought the series to an end, doing my best to orchestrate a finale that would leave both characters and readers happy--a promotion to an administrative job for Walt, so he can stop pretending he's capable of detecting anything, and a long-awaited wedding and an adventure-filled retirement for Bolt. I truly love these characters. But I'd never trust them with a novel.

Other short-story protagonists, though, do have what it takes to be protagonists in novels, too. Lord Peter Wimsey is one example--in fact, most readers would probably agree that, delightful as most of the stories about him are, the novels are even better. Sherlock Holmes is another example--four novels, fifty-six short stories, and I think it's fair to say he shines in both genres. I considered one of my own short-story protagonists so promising that I decided to build a novel around her. Before I could do that, though, I had to make some major changes in her character.

American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi first appeared in a December, 2010 Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine story, now republished as a Kindle story called "Silent Witness." Positive responses to the story--including a Derringer from the Short Mystery Fiction Society--encouraged me to think I might be able to do more with the character. It also helped that one of my daughters is an ASL interpreter who can scrutinize drafts and provide insights into deaf culture and the ethical dilemmas interpreters face. And I like Jane. She's smart, she's observant, she has acute insights into human nature, and she has a strong sense of right and wrong. In "Silent Witness," when she interprets at the trial of a deaf man accused of murdering his employer, she wants the truth to come out. She definitely doesn't want to see an innocent man go to prison.

I don't think it's enough to make her a fully satisfying protagonist in a novel--at least, not in a traditional mystery novel. In what's often called a literary novel, the Jane of "Silent Witness" might do fine--another protagonist paralyzed by doubt, agonizing endlessly about right and wrong but never taking decisive action. The protagonists of traditional mysteries should be made of sterner stuff. So in Interpretation of Murder, I made Jane regret and learn from the mistakes she'd made in "Silent Witness." We find out she did her best to correct them, even though it hurt her professionally. And when she's drawn into another murder case, she works actively to uncover the truth, she comes up with inventive ways of gathering evidence, and she speaks out about what she's discovered even when situations get dangerous. I can't be objective about Jane--others will have to decide if these changes were enough to make her an effective protagonist for Interpretation of Murder. But I'm pretty sure mystery readers would find the Jane of "Silent Witness" a disappointing companion if they had to read an entire novel about her.

Have you encountered mystery characters who are effective protagonists in short stories but not in novels--or, perhaps, in novels but not in short stories? If you're a writer, have you decided some of your protagonists work well in one genre but not in the other? If you've used the same protagonist in both stories and novels, have you had to make adjustments? I'd love to hear your comments.

18 July 2013

The Road to Damascus - or Somewhere...

by Eve Fisher

Brian Thornton blogged a couple of weeks ago about the importance of both a strong plot and well-written

characters. Now I like certain characters straight up and traditional - Sherlock

Holmes, Miss Marple, Nero Wolfe, etc. You learn more about them -

Holmes' brother, Nero's daughter, Miss Marple's flirtation so deftly

nipped in the bud by her mother - but the characters are there, fixed,

sure and solid. The down side is that they are done growing. Luckily, I

never tire of them as they are.

But I also honor the authors who manage to transform their characters over time - who change and grow into something different than the person we first met. They mature. Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane both changed over the course of the 8 novels and 2 short stories Miss Sayers wrote. The posh, flighty eccentric with a taste for flagrantly expensive, professionally beautiful women and old books became a man who wrestled - through his avocation - with his own PTSD and fell passionately in love with an intelligent woman whose main beauty was her voice. And Harriet discovered self-esteem and freedom from her fear of a cage - both in marriage and in prison.

And then there are those who pull a 180, changing to their exact opposite to the point that it's unbelievable. Except in real life, it happens all the time.

There are the obvious religious transformations, i.e., the roads to Damascus - Paul, Buddha, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Ignatius of Loyola, Abba Moses (old black guy, used to be a professional thief/murderer, became a hermit monk in the Wadi Natrun back 150 CE), etc.

Franz Liszt (1811-1886), the famous composer and pianist, and a formidable womanizer, lost his son and one of his daughters (by the Countess d'Agoult) in 1859 and 1862, respectively. (NOTE: His surviving daughter, Cosima, a musician in her own right, would marry first Hans von Bulow- does anyone know if he's an ancestor of Claus? - and then Richard Wagner.) He became a Franciscan, received the tonsure, took the four minor orders porter, lector, exorcist, acolyte, and from then on was known as Abbe Liszt. His whole life style calmed down considerably, and he spent much of his time, outside of playing, in solitude and prayer.

Liane de Pougy (1869-1950) - infamous courtesan of La Belle Epoque, she ran through men at a merry clip, accumulating massive wealth and dominating the gossip columns along with her co-courtesans, La Belle Otero, et al. She married the Romanian Prince Georges Ghika in 1910 and settled down. But her son by a much earlier marriage(?) was killed in WWI, and she became a Dominican tertiary, devoting herself to the Asylum of Saint Agnes, which took care of children with birth defects. A recent French biography of her has the subtitle "Courtesan, princess, saint..." The last might be extravagant - I haven't read the biography - but her life definitely took a different turn.

Liane de Pougy (1869-1950) - infamous courtesan of La Belle Epoque, she ran through men at a merry clip, accumulating massive wealth and dominating the gossip columns along with her co-courtesans, La Belle Otero, et al. She married the Romanian Prince Georges Ghika in 1910 and settled down. But her son by a much earlier marriage(?) was killed in WWI, and she became a Dominican tertiary, devoting herself to the Asylum of Saint Agnes, which took care of children with birth defects. A recent French biography of her has the subtitle "Courtesan, princess, saint..." The last might be extravagant - I haven't read the biography - but her life definitely took a different turn.

Speaking of courtesans and such, there are many throughout history who decided that repentance became them. Among my favorites are the rivals Louise de La Valliere and Francoise-Athenais, Marquise de Montespan:

Louise was the first "maitresse en titre" of Louis XIV, bearing him four children, which was part of the problem. Childbirth changed her fragile beauty and she was succeeded by her supposed best friend, Athenais, who held on to Louis' attention through seven pregnancies and innumerable side affairs (Louis never met a woman he didn't want to have, and, as king, he had most of them). She was finally ousted from the royal bed by the combination of a huge scandal involving multiple poisonings - next time's blog alert! - and her own governess for HER royal bastards, Madame de Maintenon, who was trying to use God to embarrass the king into morality. Louise retired to a strict Caremlite convent early in the game. (My favorite part is that the abbess of this extremely strict convent agreed that Louise had already done much of her penance in court). Interestingly, and entirely out of character, in old age, the almost heathen Athenais also turned to strict penance. Louis and Maintenon were morganatically married, and Louis remained reasonably faithful (by now he was forty-five which, at the time, was definitely middle-aged) and, as always, convinced that he was God's favorite son. (Louis would NOT be on the list of people who change over time.)

There are also those who, apparently, get a burr in their butt, such as the Wanli Emperor (1563-1620).

The Wanli Emperor came to the Dragon throne

near the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). He was 9 years old, but

had an excellent chief minister who trained him well before dying when

Wanli was 19. The next 20 years were a golden age for China - Wanli was a vigorous, active, hands-on emperor who

stopped attempted invasions by the Mongols, an attempt by Japan (under

Hideyoshi) to take Korea, and a major internal rebellion. China

prospered. And then - one day he stopped doing anything. No meetings, no

memorials, no signing things, nothing. Government came to an absolute

standstill until the day he died. Why? We don't know. There are two

possibilities given by most historians:

The Wanli Emperor came to the Dragon throne

near the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). He was 9 years old, but

had an excellent chief minister who trained him well before dying when

Wanli was 19. The next 20 years were a golden age for China - Wanli was a vigorous, active, hands-on emperor who

stopped attempted invasions by the Mongols, an attempt by Japan (under

Hideyoshi) to take Korea, and a major internal rebellion. China

prospered. And then - one day he stopped doing anything. No meetings, no

memorials, no signing things, nothing. Government came to an absolute

standstill until the day he died. Why? We don't know. There are two

possibilities given by most historians:

(1) he decided to spend the rest of his reign building up his wealth and his tomb, thus he had no time for work.

(2) he was angry because he wanted one of his sons by his concubine, Lady Zheng, to be the next crown prince, and strict court etiquette demanded that the office be passed to his son by his Empress (the future Taiching Emperor), thus bringing government to a halt was his revenge.

Personally, I don't know that either of these pass muster. I mean, for a while, but for 20 years? What would explain something like that? Depression? Addiction? A combination of both? In any case, with government at a standstill, China floundered, and the last few emperors couldn't get it back. The Wanli Emperor's dereliction of duty was one of the major reasons why the Ming Dynasty fell 24 years later to the Manchus.

And there are those who appear to really grow and CHANGE:

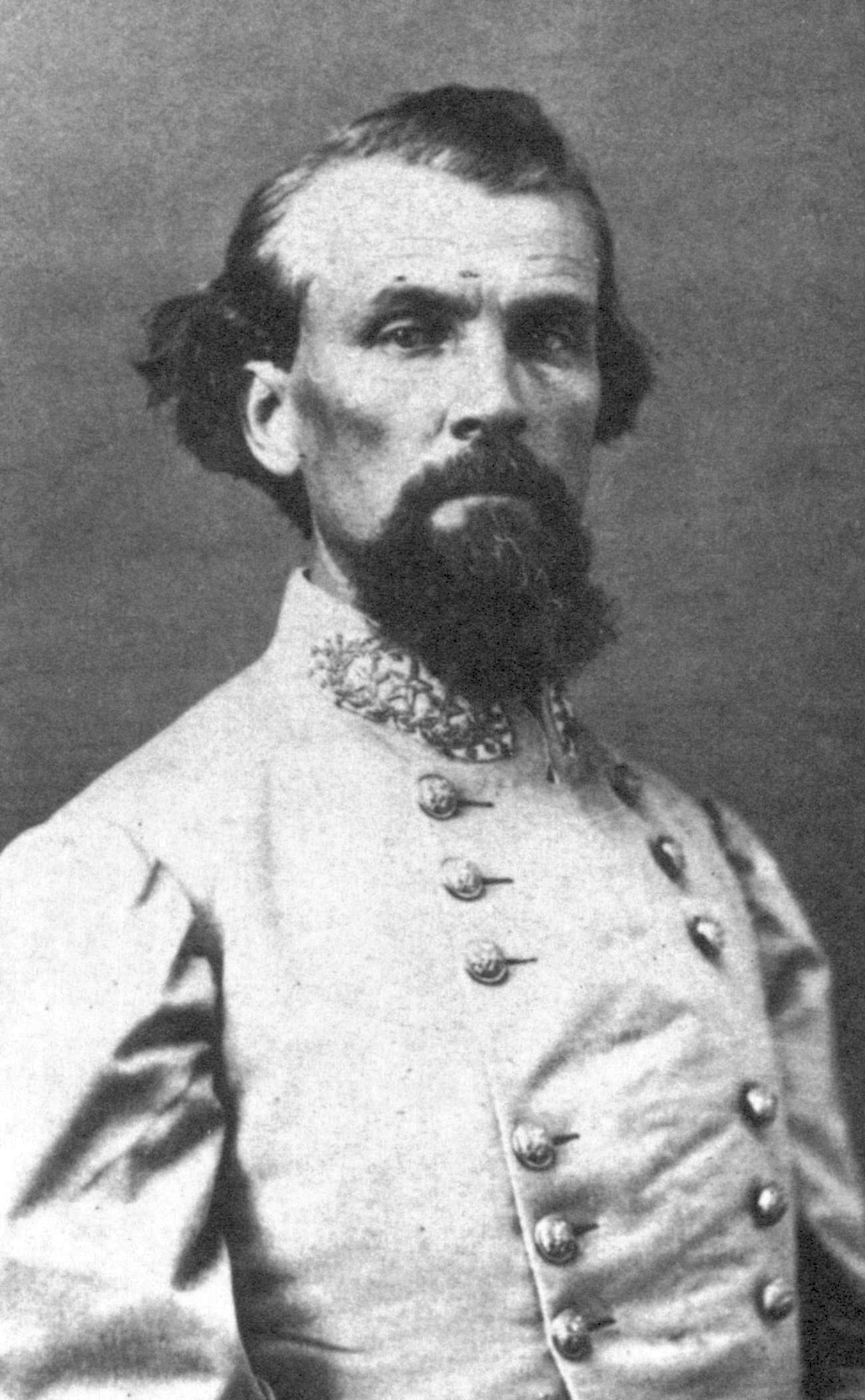

Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877) enlisted in the Civil War as a private and rose through the ranks to become a field commander. And he was brilliant. My favorite story is from the Battle of Parker's Cross Roads, 12/31/1862, when he was surprised by a Union brigade attacking his rear. Trapped between two Union forces, he told his troops "Charge 'em both ways!" - and they did, and he won. It seems like every Civil War historian is fascinated by this military genius who never attended West Point or took any military classes. But what makes Forrest fascinating to me is that he was an antebellum slave trader and millionaire, who in the 1860's was one of the founders (perhaps the first Grand Wizard) of the KKK. But barely ten years later he repudiated the Klan, and went around giving speeches advocating reconciliation between the races to both white and black organizations. In one of them, before a black organization, he said, "Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand." Yes, it sounds a little condescending to modern ears - but this is the sound of a man who had changed profoundly...

But I also honor the authors who manage to transform their characters over time - who change and grow into something different than the person we first met. They mature. Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane both changed over the course of the 8 novels and 2 short stories Miss Sayers wrote. The posh, flighty eccentric with a taste for flagrantly expensive, professionally beautiful women and old books became a man who wrestled - through his avocation - with his own PTSD and fell passionately in love with an intelligent woman whose main beauty was her voice. And Harriet discovered self-esteem and freedom from her fear of a cage - both in marriage and in prison.

And then there are those who pull a 180, changing to their exact opposite to the point that it's unbelievable. Except in real life, it happens all the time.

There are the obvious religious transformations, i.e., the roads to Damascus - Paul, Buddha, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Ignatius of Loyola, Abba Moses (old black guy, used to be a professional thief/murderer, became a hermit monk in the Wadi Natrun back 150 CE), etc.

There are those who were knocked sideways by sorrow:

|

| Young Liszt, Brooding and Burning |

|

| Liszt, Older and Mourning |

Franz Liszt (1811-1886), the famous composer and pianist, and a formidable womanizer, lost his son and one of his daughters (by the Countess d'Agoult) in 1859 and 1862, respectively. (NOTE: His surviving daughter, Cosima, a musician in her own right, would marry first Hans von Bulow- does anyone know if he's an ancestor of Claus? - and then Richard Wagner.) He became a Franciscan, received the tonsure, took the four minor orders porter, lector, exorcist, acolyte, and from then on was known as Abbe Liszt. His whole life style calmed down considerably, and he spent much of his time, outside of playing, in solitude and prayer.

Liane de Pougy (1869-1950) - infamous courtesan of La Belle Epoque, she ran through men at a merry clip, accumulating massive wealth and dominating the gossip columns along with her co-courtesans, La Belle Otero, et al. She married the Romanian Prince Georges Ghika in 1910 and settled down. But her son by a much earlier marriage(?) was killed in WWI, and she became a Dominican tertiary, devoting herself to the Asylum of Saint Agnes, which took care of children with birth defects. A recent French biography of her has the subtitle "Courtesan, princess, saint..." The last might be extravagant - I haven't read the biography - but her life definitely took a different turn.

Liane de Pougy (1869-1950) - infamous courtesan of La Belle Epoque, she ran through men at a merry clip, accumulating massive wealth and dominating the gossip columns along with her co-courtesans, La Belle Otero, et al. She married the Romanian Prince Georges Ghika in 1910 and settled down. But her son by a much earlier marriage(?) was killed in WWI, and she became a Dominican tertiary, devoting herself to the Asylum of Saint Agnes, which took care of children with birth defects. A recent French biography of her has the subtitle "Courtesan, princess, saint..." The last might be extravagant - I haven't read the biography - but her life definitely took a different turn.Speaking of courtesans and such, there are many throughout history who decided that repentance became them. Among my favorites are the rivals Louise de La Valliere and Francoise-Athenais, Marquise de Montespan:

|

| Louise de la Valliere and children on left; Athenais de Montespan on right |

Louise was the first "maitresse en titre" of Louis XIV, bearing him four children, which was part of the problem. Childbirth changed her fragile beauty and she was succeeded by her supposed best friend, Athenais, who held on to Louis' attention through seven pregnancies and innumerable side affairs (Louis never met a woman he didn't want to have, and, as king, he had most of them). She was finally ousted from the royal bed by the combination of a huge scandal involving multiple poisonings - next time's blog alert! - and her own governess for HER royal bastards, Madame de Maintenon, who was trying to use God to embarrass the king into morality. Louise retired to a strict Caremlite convent early in the game. (My favorite part is that the abbess of this extremely strict convent agreed that Louise had already done much of her penance in court). Interestingly, and entirely out of character, in old age, the almost heathen Athenais also turned to strict penance. Louis and Maintenon were morganatically married, and Louis remained reasonably faithful (by now he was forty-five which, at the time, was definitely middle-aged) and, as always, convinced that he was God's favorite son. (Louis would NOT be on the list of people who change over time.)

There are also those who, apparently, get a burr in their butt, such as the Wanli Emperor (1563-1620).

The Wanli Emperor came to the Dragon throne

near the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). He was 9 years old, but

had an excellent chief minister who trained him well before dying when

Wanli was 19. The next 20 years were a golden age for China - Wanli was a vigorous, active, hands-on emperor who

stopped attempted invasions by the Mongols, an attempt by Japan (under

Hideyoshi) to take Korea, and a major internal rebellion. China

prospered. And then - one day he stopped doing anything. No meetings, no

memorials, no signing things, nothing. Government came to an absolute

standstill until the day he died. Why? We don't know. There are two

possibilities given by most historians:

The Wanli Emperor came to the Dragon throne

near the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). He was 9 years old, but

had an excellent chief minister who trained him well before dying when

Wanli was 19. The next 20 years were a golden age for China - Wanli was a vigorous, active, hands-on emperor who

stopped attempted invasions by the Mongols, an attempt by Japan (under

Hideyoshi) to take Korea, and a major internal rebellion. China

prospered. And then - one day he stopped doing anything. No meetings, no

memorials, no signing things, nothing. Government came to an absolute

standstill until the day he died. Why? We don't know. There are two

possibilities given by most historians:(1) he decided to spend the rest of his reign building up his wealth and his tomb, thus he had no time for work.

(2) he was angry because he wanted one of his sons by his concubine, Lady Zheng, to be the next crown prince, and strict court etiquette demanded that the office be passed to his son by his Empress (the future Taiching Emperor), thus bringing government to a halt was his revenge.

Personally, I don't know that either of these pass muster. I mean, for a while, but for 20 years? What would explain something like that? Depression? Addiction? A combination of both? In any case, with government at a standstill, China floundered, and the last few emperors couldn't get it back. The Wanli Emperor's dereliction of duty was one of the major reasons why the Ming Dynasty fell 24 years later to the Manchus.

And there are those who appear to really grow and CHANGE:

Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877) enlisted in the Civil War as a private and rose through the ranks to become a field commander. And he was brilliant. My favorite story is from the Battle of Parker's Cross Roads, 12/31/1862, when he was surprised by a Union brigade attacking his rear. Trapped between two Union forces, he told his troops "Charge 'em both ways!" - and they did, and he won. It seems like every Civil War historian is fascinated by this military genius who never attended West Point or took any military classes. But what makes Forrest fascinating to me is that he was an antebellum slave trader and millionaire, who in the 1860's was one of the founders (perhaps the first Grand Wizard) of the KKK. But barely ten years later he repudiated the Klan, and went around giving speeches advocating reconciliation between the races to both white and black organizations. In one of them, before a black organization, he said, "Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand." Yes, it sounds a little condescending to modern ears - but this is the sound of a man who had changed profoundly...

Labels:

characters,

Dorothy Sayers,

Eve Fisher,

Lord Peter Wimsey,

Miss Marple,

Nero Wolfe,

Sherlock Holmes

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)