by Paul D. Marks

Today I’m giving over my post to the 2017

Macavity Award Short Story Nominees. There’s six of us and I’m both lucky and honored to be among such truly distinguished company. It’s mind blowing. Really!

The envelope please. And the nominees are (in alphabetical order as they will be throughout this piece):

Lawrence Block,

Craig Faustus Buck,

Greg Herren,

Paul D. Marks,

Joyce Carol Oates and

Art Taylor. Wow!

I want to thank Janet Rudolph who puts it all together. And I want to thank everyone who voted for us in the first round. If you’re eligible to vote there’s still a few days left – ballots are due September 1st, and I hope you’ll take the time to check out the links below and read all the stories.

But even if you’re not eligible to vote, I hope you’ll take the time to read the stories. I think you’ll enjoy them and maybe get turned onto some new writers. Our

Bios are at the end of this post.

So without further ado, here’s our question and responses:

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

“What inspired your Macavity-nominated story? Where did the idea and characters come from?”

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Lawrence Block: “Autumn at the Automat,” (In Sunlight or in Shadow, Pegasus Books). Story link: http://amzn.to/2vsnyBP

When I got the idea for an anthology of stories based on Edward Hopper paintings, the first thing I did was draw up a list of writers to invite. I explained the book’s premise and invited each to select a painting.

The response surprised me. Almost everyone on my wish list accepted, picked a painting, and went to work. Now it fell to me to go and do likewise, and I began viewing the paintings and waiting for inspiration to strike. I considered several works—everything Hopper painted somehow manages to suggest there’s a story waiting to be told—and when I looked a second time at “Automat,” the germ of the story came to me.

But there was a problem. “Automat” was off the table. Kristine Kathryn Rusch had already laid claim to it.

I tried to find a way out, but all I could think of was the story that had come to me, as it evolved in my mind. So I emailed Kris, explained where I was, and asked her how strongly committed she was to that particular painting. Had she begun work on a story?

She could not have been more gracious, replying at once that she’d picked “Automat” because she’d had to pick something, that she hadn’t yet come up with a plot and characters, and could as easily transfer her affections to something else. I thanked her, and that same day I sat down and started writing. If I remember correctly, an increasingly tenuous proposition with the passing years, I wrote the story in a single session at the computer. It was already there in my mind, waiting for my fingers to catch up with it.

Kris promptly selected another painting, “Hotel Room 1931,” and knocked my socks off with her story, Still Life 1931, which she elected to publish under her occasional pen name, Kris Nelscott.

So that’s the story.

***

Craig Faustus Buck: “Blank Shot,” (Black Coffee, Darkhouse Books). Story link: http://tinyurl.com/BlankShot-Buck

“Blank Shot” was the result of two writing issues coming together in the right place at the right time. I'd been asked by someone to blog about openings, so I'd been thinking about my favorite way to start a story, which is with a bang. So I wrote an example: "His face hit the pavement hard."

I wrote my blog and found myself wondering what happened next to the hapless fellow in my example. At the same time, I'd been reading a Cold War thriller about Berlin in the time of the Wall, and I wondered what Berlin had been like before the Wall went up, but after it had been divided after WWII. I did a bit of research and became fascinated with this period of a divided city that had open commerce and transportation between the sides, yet still maintained a heavily guarded border without barriers between them.

I decided to take my opening line, put it in 1960 Berlin, and see what happened. The result was a hoot to write and full of surprises for me as my characters developed. The ending really came as a shock. Of course, I had to do a lot of back-filling and tap dancing to motivate it and make it work, but that was the fun part.

Once again, writing by the seat of my pants, instead of outlining, turned the work of writing into play. I truly believe that when authors allow their characters to do the driving, the journey is more enjoyable for both writer and reader, and the destination is more likely to delight.

***

Greg Herren: “Survivor’s Guilt,” (Blood on the Bayou: Bouchercon Anthology 2016, Down & Out Books). Story link: https://gregwritesblog.com/2017/07/21/cant-stop-the-world/

My story was inspired, in part, by the stories I heard from people who did not evacuate from New Orleans before the levees failed; what it was like to be up on the roof, running out of water, and drinking alcohol because that was all that was left while waiting to be rescued. A married couple—friends of friends— got divorced because the wife had wanted to evacuate and the husband didn’t; they were on their roof for four days. That dynamic—the blame and guilt—fascinated me, as did the mental anguish. That kind of trauma changes people.

As I listened to the husband tell his story, through my horror at what they endured, I thought: what if they had argued and he’d accidentally killed her?

After all, the victim’s body wouldn’t have been found for months, and by then, the water and decay would have certainly done a number on the corpse; and the bodies weren’t autopsied. It seemed almost like it would be the perfect crime. The body might not ever be identified, and the husband could just disappear, as so many did in the vast diaspora that followed.

As for the characters in my story, I had started with the story and worked backward. I made them blue collar, because of most of the people who lived in the lower 9th were, and began piecing together who they were, and what their marriage had been like. It all just kind of fell into place as I wrote the story.

***

Paul D. Marks: “Ghosts of Bunker Hill,” (Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, Dec. 2016). Story link: http://www.elleryqueenmysterymagazine.com/assets/3/6/EQMD16_Marks_BunkerHill.pdf

My story “Ghosts of Bunker Hill” is partly inspired by the Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles. Bunker Hill was L.A.’s first wealthy residential neighborhood, right near downtown. It was filled with fantastic Victorian mansions, as well as offices, storefronts, hotels, etc. After World War I the swells moved west and the neighborhood got run down and became housing for poor people. It wasn’t

shiny enough for the Powers That Be, who wanted to build up and refurbish downtown. Out with the old, the poor, the lonely, in with the new, the young, the hip. So in the late 60s they tore it down and redeveloped it. Luckily, some of those Victorians were moved to other parts of L.A. If you’re into film noir you’ve seen the original Bunker Hill. And when I was younger I explored it with friends, even “borrowing” a souvenir or two. And that place has always stayed with me.

In the story, P.I. Howard Hamm is investigating his best friend’s murder and, while the murder takes place today in one of those “moved” Victorians, “ghosts” of the past influence the present.

As it says in “Bunker Hill Blues,” the sequel to “Ghosts of Bunker Hill,” which is in the current September/October 2017 issue of Ellery Queen, but which also applies to the first Bunker Hill story:

“Howard might not have believed in ghosts, but they were everywhere if you knew where to look for them: There are more things in heaven and earth, and all that jazz. Not creatures in white sheets like Casper, not malevolent apparitions like in Poltergeist. But ghosts of the past, ghosts of who we were and who we thought we wanted to be. Ghosts of our lost dreams. In some ways those ghosts are always gaining on us, aren’t they?”

***

Joyce Carol Oates: “The Crawl Space,” (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Sep.–Oct. 2016). Story link: http://www.elleryqueenmysterymagazine.com/assets/3/6/EQM916_Oates_CrawlSpace.pdf

(Note: I couldn’t reach Joyce Carol Oates, but Janet Hutchings, editor of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, provided me with the following and with Ms. Oates’ bio at the end of this piece.)

|

| Photo by Larry D. Moore © 2014 |

“The Crawl Space” by Joyce Carol Oates was written in response to an invitation from Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine to contribute to its special 75th-anniversary issue, September/October 2016. The author explained the seed for the story when she spoke at the EQMM 75th Anniversary Symposium at Columbia University in September 2016:

“‘The Crawl Space’ . . . gives me a shiver because it’s set in my former house…. There was a crawl space in that house. If you know what a crawl space is, it’s some strange part of a cellar—it’s not completely filled in. Sometimes there is a cellar and the crawl space goes out from it, but this particular house didn’t have a cellar. It only had a crawl space. There were things stored there, and I think repairmen would have to crawl in there and do things—and I think they never came out again....If you have an imagination, you can just imagine how horrible it would be to be in a crawl space. So the story’s about that dark fantasy that comes true for someone.”

Ms. Oates added, that despite being set in her former home, the story is “NOT autobiographical”!

***

Art Taylor: “Parallel Play,” (Chesapeake Crimes: Storm Warning, Wildside Press). Story link: http://www.arttaylorwriter.com/books/6715-2/

My story “Parallel Play” centers on new parenthood, both the stress and anxieties surrounding it and then the idea of parental protectiveness—the thought that most parents will do whatever it takes to protect their children. The opening to the story is set at a kids play space which I call Teeter Toddlers, and the idea of the story actually first came to me when I was taking my own son, Dashiell, to his weekly Gymboree classes. I was the only father who regularly attended, and while the moms there were certainly welcoming to me, they did seem to form quicker friendships, share more quickly, with one another than with me—some small gender divide, I guess, and probably not surprising, but I did start wondering about various dynamics and situations, letting my mind wander (as we crime writers do) into darker twists and turns. Another inspiration was the prompt from the anthology

Chesapeake Crimes: Storm Warning, which required weather to play an important role. The Gymboree had big plate glass windows surrounding the play space, and I remember one day watching a thunderstorm roll into view. That image plus one more element—a forgotten umbrella—and the rest of the story was suddenly in motion. I hope that readers will appreciate where it all goes.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

BIOS:

Lawrence Block has been writing award-winning mystery and suspense fiction for half a century. His series characters include Matthew Scudder, Bernie Rhodenbarr, Chip Harrison, Evan Tanner, Martin Ehrengraf, and a chap called Keller. His non-series characters include, well, hundreds of other folk. Liam Neeson starred in the film version of his novel, A Walk Among the Tombstones. Several of his other books have also been filmed, although not terribly well. In December Pegasus Books will publish Alive in Shape and Color, a sequel to his Hopper anthology In Sunlight or in Shadow. LB is a modest and humble fellow, although you would never guess as much from this biographical note.

http://lawrenceblock.com/

Author-screenwriter

Craig Faustus Buck's short crime fiction has won a Macavity Award and has been nominated for a second, plus two Anthonys, two Derringers and a Silver Falchion. His novel, Go Down Hard (Brash Books), a noir romp, was First Runner Up for the Claymore Award. The sequel, Go Down Screaming, is coming out whenever he writes his way out of the second act.

CraigFaustusBuck.com

Greg Herren is the award-winning author of over thirty novels, and an award-winning editor, with twenty anthologies to his credit. He has published numerous short stories, in markets as varied as Men magazine to the critically acclaimed New Orleans Noir to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, and his story "Keeper of the Flame" is scheduled for an upcoming issue of Mystery Week. He has written two detective series set in New Orleans. His most recent novel, Garden District Gothic, was released in September 2016. He lives in New Orleans with his partner of twenty-two years, and is currently finishing another novel.

http://gregherren.com/

Paul D. Marks is the author of the Shamus Award-Winning mystery-thriller White Heat. Publishers Weekly calls White Heat a “taut crime yarn.” His story Ghosts of Bunker Hill was voted #1 in the Ellery Queen Readers Poll and is nominated for a Macavity Award. Howling at the Moon was short-listed for both the Anthony and Macavity Awards. Midwest Review calls his novella Vortex “…a nonstop staccato action noir.” His short stories can be found in Ellery Queen and Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine/s, as well as various periodicals and anthologies, including St. Louis Noir. He is also the co-editor of the Coast to Coast series of mystery anthologies for Down & Out Books.

www.PaulDMarks.com

Joyce Carol Oates is a winner of the National Book Award, two O. Henry Awards, and a National Medal of the Humanities (among many other honors). One of America’s most celebrated literary writers, she is the author of more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories, most under her own name but a number employing her crime-writing pseudonyms Rosamond Smith and Lauren Kelly. Her honors in the field of crime fiction include two International Thriller Awards for best short story.

https://celestialtimepiece.com/

Art Taylor is the author of On the Road with Del & Louise: A Novel in Stories, winner of the Agatha Award for Best First Novel. He has won three additional Agatha Awards, an Anthony Award, a Macavity Award, and three consecutive Derringer Awards for his short fiction, and his work has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories. He is an associate professor of English at George Mason University.

http://www.arttaylorwriter.com/

###

And now for the usual BSP.

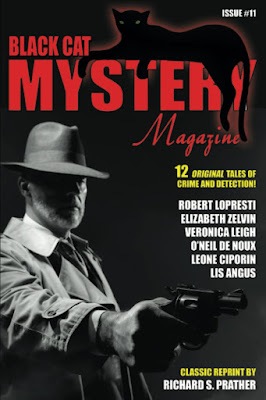

I’m happy to say that my short story “Bunker Hill Blues” is in the current Sept./Oct. issue of Ellery Queen that hit newsstands Tuesday of this week. It’s the sequel to the 2016 Ellery Queen Readers Poll winner and current Macavity Award nominee “Ghosts of Bunker Hill”. And I’m surprised and thrilled to say that I made the cover of the issue – my first time as a 'cover boy'! Hope you’ll want to check it out. Available at all the usual places.

My story “Blood Moon” appears in “Day of the Dark, Stories of the Eclipse” from Wildside Press, edited by Kaye George. Stories about the eclipse – just in time for the real eclipse on August 21st. Twenty-four stories in all. Available on

Amazon.