|

| Photo by Stephen E. Morton |

A special treat today. Kevin Egan is the author of eight novels and more than 40 short stories. His three legal thrillers, each set in the New York County Courthouse, were inspired by his 30 years as a staff attorney in that iconic building. Kirkus Reviews listed his Midnight as a Best Book of 2013.He has appeared in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, Mystery Tribune, Mystery Magazine, and Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine.And now he's appearing for you. - Robert Lopresti

NOVEL TO SHORT STORY TO NOVEL (AGAIN)

by Kevin Egan

In

the early 2000s, I experienced a writing crisis. I had published four

novels, including a three-book golf mystery series, but my dream of

writing "bigger" novels had vanished in a welter of half-baked ideas. My

agent, more than once, suggested that I look to my day job as a source

of ideas. At the time, I was a law clerk to a judge in the New York

County Supreme Court. Wouldn't some of the cases I observed lend

themselves to a novel? I didn't think so. This was a civil courthouse,

not a criminal courthouse, and the trials I observed, though they may

have been interesting in the legal sense, were hardly dramatic in the

novelistic sense.

I decided to take a different tack -- writing a courthouse novel that would take place not in a courtroom but in a judge's chambers. A standard chambers in the New York County Courthouse is a self-contained three-room suite that evolves its own culture, dynamic, and morality. Three people populate this unique world: the judge, the law clerk, and secretary. As my real-life judge described at the time, judge and staff essentially "live in each other's pockets" for 40 hours a week. And three people, as the saying goes, are a crowd, which in chambers can manifest itself as an ever-changing kaleidoscope of allegiances and alliances.

With this setting firmly in mind, I came up with ... another half-baked idea. My plot involved: a judge who has just presided over a bench trial targeting a powerful union boss; a hapless law clerk secretly in love with the secretary; and a secretary who recently ended her own secret affair with the judge.

The story opens on the Third Monday in July (the working title) when the staff arrive to find a thug sitting behind the judge's desk. He informs them that the judge tragically died over the weekend, that the union boss has secreted the body in a friendly funeral home, and that the law clerk and secretary are to collaborate on writing a post-trial ruling that awards a multi-million dollar judgment to the union boss.

I banged out almost 400 pages of this mess, and my agent actually tried to sell it. (She later confessed that she never expected it to sell; she merely hoped that some editor somewhere would volunteer to collaborate on a re-write.) After seeing the comments she received (several of which incorporated the phrase "willing suspension of disbelief"), I returned to the comfort of launching yet another golf mystery series.

A few years later, I saw a

manuscript call for a MWA anthology. The theme for the anthology was

institutional law enforcement -- the police, the FBI, the courts. Hmm, I

thought. I work in the courts, maybe I should submit a story to the

anthology.

Ideas come slowly to me. Rarely have I experienced the "flash of creative genius" touted in my Patents & Copyrights course in law school. The only idea that kept popping into my head was that ridiculous Third Monday in July plot, which at the very least I would need to miniaturize into a 20 page story.

That necessity sparked new and critical ideas on how to construct the story.

First, I decided that the judge's staff needed to be actors, not pawns or victims. They needed to have a definite plan and a definite stake in the outcome. But what?

Second, I needed to have a clock running. The novel's time-line meandered through most of the month of July, which strained the reader's suspension of disbelief as well as my own imagination. But how fast?

|

I found the answers to both questions in the New York Judiciary Law. By law, a judge is entitled to two personal assistants -- a law clerk and a secretary. By law, these assistants are personal appointments who serve at the pleasure of the judge and therefore can conceivably keep their jobs for the entire length of the judge's 14-year term. Also, by law, if the judge dies during that term, the assistants keep their jobs until the governor appoints a successor. As a practical matter, and partly for political reasons, the governor usually delays appointing the successor of a deceased judge until the end of that year. Therefore (because I'd seen it often enough), the staff of a deceased judge usually can bank on keeping their jobs until the end of the calendar year in which their judge has died.

Consequently, if you work for a judge, the worst day of the year for the judge to die would be New Year's Eve. The best day? Obviously New Year's Day itself.

Thus, the short story "Midnight" was born. A judge dies in chambers on the morning of December 31. The law clerk and the secretary, both desperately seeking to keep their jobs, hit upon a plan to "float" the body to make it appear that the judge died after midnight. The odds are in their favor: the courthouse is virtually empty on the day before the holiday, the judge is elderly and not in good health, and the judge is one of the few judges who owns a car and actually drove it to the courthouse that day. Plus, the judge's only family is a brother who lives in Florida.

The law clerk and the secretary spirit the body out of the courthouse after dark, drive to the judge's apartment, and tuck the body into bed. They wait in the apartment until well after midnight, then go to their homes. They arrive back at the courthouse on January 2, planning to report the judge as missing when he doesn't show up in chambers by the end of the morning. But then, of course, the unexpected happens.

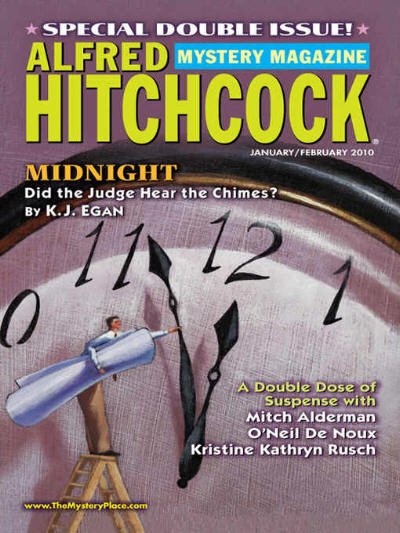

I missed the deadline for submitting the story to the MWA anthology. Instead, I submitted it to Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. I was thrilled when Linda Landrigan accepted the story and even more thrilled to see it featured on the cover of the January-February 2010 issue of the magazine. But beyond the thrill of the story appearing in one of the finest and most respected mystery publications, I knew that the act of miniaturizing that original embarrassment of a novel created the blueprint for writing a new one.

Two years later, I finished

writing Midnight the novel. The short story, expanded from 20 pages to

just over 100 pages, became the first day of a four day timeline that

runs from December 31 to January 3. Structurally, each day presents a

new problem for the desperate duo to solve, and each day they seem to

overcome that problem only to discover that they have unwittingly

created a more complicated obstacle until ultimately ... well, you need

to read the book.