Of Novels and Noir

I’m a member (if you can call being a part of such a loose-knit group a

member) of the Hardboiled Discussion Group at the Poisoned Pen bookstore here in Scottsdale. I’m sure you understand how such a thing works: everybody in the group reads a certain novel each month, then we meet at the store, after hours, to discuss it. In this case, a fellow named Patrick Millikin, who’s worked there for over a decade (and also edited the anthology

Phoenix Noir), chairs the group and helps us decide which novels we’ll read for the month

I don’t always manage to get to the meetings, but I usually manage to read the book for the month. So, over the past few months I’ve read several noir mysteries. Of those, the two that stand out as the most wonderfully contrasting works are James M. Cain’s

Mildred Pierce and Sara Gran’s

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead. One a grimly realist work, the other a flight of fancy that still manages to be rather grim yet holds an artistic aspect I don't recall encountering before in literature.

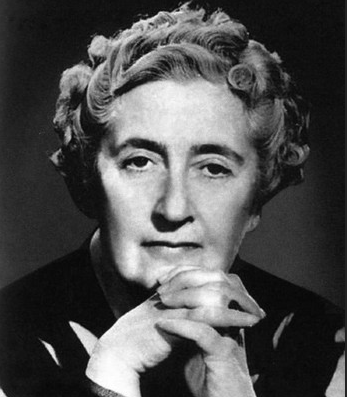

|

| James M. Cain |

Mildred Pierce is probably the more widely known of the two, of course, James M. Cain being the writer of classics such as:

The Postman Always Rings Twice and

Double Indemnity.

Mildred Pierce has been around for decades, but I only met her this past summer—thanks to the group’s introduction.

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead, on the other hand, is a fairly recent novel – second or third in a contemporary series, which I understand is planned for five installments.

I said the two works contrast wonderfully, and they do. Which is . . .

Almost the Point of this Post:

Among the books I've read by Cain,

Mildred Pierce probably stands as one of the best examples of Cain holding himself in check, keeping a tight reign on his natural tendency to let everything devolve into a murderous blood bath. As such, I found it based in greater realism—the realism of its time, at least.

Claire DeWitt, however, includes magical thinking, a holistic approach to detection and hints of Voodoo -- all connected inextricably to the painful realism of post-Katrina New Orleans: a remarkably gripping combination.

The two novels easily compare, in my mind, because neither was what I expected, and both consistently diverged from paths I thought the novels were about to take.

In the case of

Mildred Pierce, one of the first such occurrences took place soon after Mrs. Pierce’s husband left her with two daughters, and she was not easily able to find employment. “Okay,” I thought. “This is going to be a noir mystery or suspense plot, so -- This is going to be the story of an abandoned woman who winds up becoming a prostitute, then works her way to 'madam' of her own establishment. In the end, she’ll be laid low by the realization that her favorite daughter has become a sex worker in either her own establishment, or that of a rival.” I was, of course, wrong. How wrong? Well, if you haven’t read the novel, I encourage you to read it and find out.

There really isn't much of a "mystery" in

Mildred Pierce, though there are plenty of quasi-legal shenanigans. But, there is a mystery in

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead. In fact, I finally decided that there are at least

two mysteries.

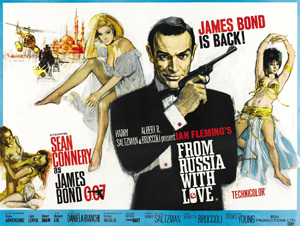

|

| Sara Gran, author of the Clair DeWitt series |

Claire DeWitt (the novel's protagonist) has studied to become a detective by reading

Detection, a book written by supposedly great French detective (or "mad man", depending on who's doing the describing) Jacques Silette. She then, as we learn in the book, apprenticed under a woman who had known Silette and had -- in her own turn -- apprenticed (as well as evidently doing other things) under him.

One of the tenants evidently set forth by Silette is: "The client already knows the solution to the mystery. But he doesn't want to know. He doesn't hire a detective to solve his mystery. He hires a detective to prove that his mystery can't be solved."

When I hit this paragraph, at the top of page three, I got the idea it meant:

A person close to a murder victim won't like learning why he was murdered, because it may reveal unsavory things about the victim's life. And, those unsavory things may be what he was murdered for. And, to an extent, I was right. The mystery at the core of the novel isn't hard to figure out; I had it pegged pretty early on -- as did many of the other group members. But, the core mystery isn't necessarily what you want to read the book for.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill out of context: "This book is a mystery wrapped in an enigma." The core mystery is wrapped in a kaleidoscope of clues, odd extraneous-seeming events and depictions, and pseudo-clues -- and the reason behind them is what makes the read worthwhile (IMHO).

Elements of the Enigma

At first read, ridiculous absurdities seemed to clutter the pages, squeezing the story out of my mind. Among them:

- A small boy has a .44 Magnum concealed in his pants at one point.

- An off-duty police officer works as security while carrying only "a .22 caliber revolver."

- Complaining about having to give constant updates about the case status, the first-person narrator writes: "Scientists don't give updates. As far as I know no one asks a painter for an update, or a chef."

- At one point, Claire DeWitt recalls a past occasion, in which the police were unable to... (Well, I'd better leave that one for you to see for yourself. Let me assure you, however, that the resulting solution contains a massive absurdity.)

Now I've handled a .44 Magnum, and I can assure you that I -- a grown man -- couldn't possibly conceal such a side arm in my pants. Not unless I wanted to walk around and have everyone ask me, "Is that a .44 Magnum in your pants, or are you just happy to see me today?"

When I asked some of my cop buddies if they'd carry a .22 revolver on off-duty security work, they looked at me like I had three heads and scoffed at the idea. One actually said, "That'd be absurd."

For those who think scientists don't give updates, let me assure you that my relatives who conduct scientific work in universities have to give constant updates. Otherwise the money funding their work dries up very quickly. As for painters: Seems like folks ask my house painter friend "How long until you're done?" to the point that he sometimes feels all he's doing is answering that question instead of painting. My wife continuously asks my son -- the artist type of painter -- for updates on his latest work in progress, just as she keeps asking me, "How long until you make enough money off your writing so that I can quit my job?" As for asking a chef for updates.... Well, ask a chef and I think you'll find he feels constantly harassed while cooking.

These glaring absurdities at first caused me problems.

Does the author not realize how wrong she's got it? I wondered.

At the same time, Claire's rather holistic approach to detection made me recall another book I'd read, long ago: Douglas Adams'

Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency. The Douglas Adams book, however, was a comedy.

Claire DeWitt may be many things, but I don't think I'd call it a comedy.

On the other hand, I thought,

maybe it is, but I'm just not getting it. If this was the case, then Sara Gran wasn't letting us in on the joke, the way Douglas Adams had. And, one reason I felt this way, was because too many of the occurrences were too similar to certain mistakes I'd seen ignorant writers make in the past.

Is Sara Gran ignorant? I wondered.

Or, is she doing this on purpose, for some reason?

I arrived at my book club still wondering. About half the group that night, really didn't get the book (myself included), but the other half loved it. At one point a woman said, "It's interesting that, though many of us say we didn't like it, we can't stop talking about it." And, indeed, we not only had a much-larger-than-normal group, that night, but stuck around discussing the work for nearly twice the usual time.

Some of the members had seen Ms. Gran, when she came to speak on a book tour. I asked them if she struck them as the sort of person who would make such mistakes. Could she, in their opinion, be ignorant? To the last, each ensured me she was clearly very intelligent, and they were convinced she had included these absurd occurrences very intentionally.

And, along the way, I discovered that those who loved the book really didn't love it as a mystery, per se. Instead, they enjoyed some esoteric quality about the book, which they couldn't really explain. I listened to them, thinking maybe they were onto something. And, on the drive home, I realized:

The Glaring Absurdities are the Point of the Story

I submit that

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead is an example of a very specific type of absurdist literature. Other examples of absurdist lit sprang to mind on that drive home, chief among them:

The World According to Garp. But, there was something different about

Claire DeWitt. The plotline was superimposed over the backdrop of post-Katrina New Orleans, a setting so strong that it seemed to grow out from the backdrop in a way that turned setting into an additional character. And this character was harsh, glaring and pain-filled, as well as mysterious and magical.

That wasn't the only thing the plotline rested upon, however. It also hung on very solid mystery elements, as if it were straddling a contemporary mystery line and the background-character at the same time.

Why?

Finally, on that drive home, I reflected on a Modern Art class I'd taken years ago in college. There, I came to understand that appreciation for Modern Art required more than just viewing

: it also required work on the viewer's part, and sometimes benefited from a little explanation. In short, I had to alter the way I thought about what I was looking at (or

: "interacting with").

Marcel Duchamp's

Nude Descending a Staircase No.2, for instance, caused one reviewer of New York's Armory Show, in 1913, to write that it resembled "an explosion in a shingle factory." Looking at the work (on the left), you can see why. But, that critic was missing the point of the painting. Duchamp's work was not meant to capture one moment in time, as a young lady with no clothing came down a spiral staircase; it was instead an attempt to capture her

entire movement down that staircase. Some of us could undoubtedly capture a similar image -- though probably more blurred -- by using a film camera loaded with very slow film, employing low light, and leaving the aperture wide open as a naked woman walked down a spiral staircase. To get closer to Duchamp's final product, however (a relatively un-blurred collection of still shots), it would probably be necessary to shoot a series of still shots -- without advancing the frame, so that they all fell on the same negative -- as she came down. Either way, the difference between comprehension and non-comprehension, concerning the painting, comes down to whether or not the person viewing (or interacting) with it understands the intent behind it.

Roughly seven years later, Duchamp created L.H.O.O.Q. which can be seen on the right. He was said to have created this work by drawing a pencil mustache and beard on a postcard reproduction of the Mona Lisa, adding the letters L.H.O.O.Q. to the bottom. The five letters are a bit of a quip. In English, we can read them as "Look", but in french the pronunciation sounds like the french phrase meaning: "She has hot pants" (or a hot something else, if you want to be more literal perhaps).

L.H.O.O.Q. is generally taken as one of Duchamp's attempts at Dadaism, an art movement that arose from artist's negative reactions to the horrors of the First World War. Dadaism (or Dada) largely

rejected reason and logic, instead prizing nonsense,

irrationality and intuition. The word Dada, itself, may have been coined because it sounded like a "nonsense" word, or because it is the French word for Hobbyhorse, which one of the artists in the movement arrived at through random means.

L.H.O.O.Q. fits into the Dadaist camp, in many people's minds, because it would appear to be Duchamp's slap in the face of an iconic art form (the Mona Lisa) while simultaneously pointing up the "unacceptable way" that icon had been used to line pockets.

And, I think it's important to note that, without the Mona Lisa image behind it, we'd be left with just a penciled mustache-beard floating in air, and the initials below. Still nonsensical, but hardly worthy of note nearly a century later. Earlier, I wrote that I believe Sara Gran's latest novel is

a particular type of absurdist literature. Were it just a novel of absurdities – as I perceive

The World According to Garp to have been – instead of being constructed around a more standard format, then I would simply list it as another example of absurdist literature. It's the mystery anchor, here, as well as the depth of setting, that I believe lifts it into another realm of literary art form. The two together, in my opinion, work in a manner similar to the Mona Lisa image in L.H.O.O.Q.

Thus, to me,

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead fits the Dada mold, because it is a work of absurdity (or nonsense) prizing irrationality and intuition (the "holistic approach" detective methods used in the novel) and is superimposed over a standard mystery and deep background "anchor". (The mystery being

: What happened to a guy everybody said was a nice, helpful, friendly person with no enemies, during the first days following Katrina's landfall in New Orleans? And, what has become of his remains?)

I'd say, if you want to look at glaring realism, in which the artist has worked mightily to hold himself in check – take a gander at

Mildred Pierce. But, if you want to see a work that demonstrates just as much harsh realism, but in which the writer works equally hard to produce something perhaps even more transcendent – read

Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead.

Or, do yourself a real favor –

READ THEM BOTH!!

Either way, I'll see ya' in two weeks, buddy!

— Dixon