|

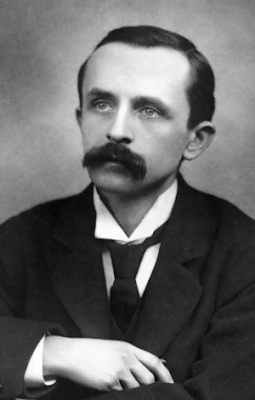

| James

Matthew Barrie (Peter Pan) |

|---|

|

| Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes) |

Did you ever wonder what might happen if Sherlock Holmes met Peter Pan? Wonder no more; it actually happened– sort of.

J. M. Barrie and A. Conan Doyle were fast friends. By 1892, Doyle was well established and Barrie was beginning to make a name for himself. The first glimpse of Peter Pan wouldn’t appear for another decade, and would continue to be revised for another ten years.

Nonetheless, Barrie had developed enough of a reputation to broach the subject of an opera to the masterful head of the Savoy Theatre formerly known for Gilbert & Sullivan operas. Richard D’Oyly Carte approved Barrie’s idea of a comic operetta titled Jane Annie or The Good Conduct Prize. D’Oyly Carte recommended ‘the’ Arthur Sullivan score the music, but Sullivan suggested a former pupil, Ernest Ford.

During his writing, Barrie suffered a breakdown. He turned to his friend, Arthur Conan Doyle.

As collaborators, Doyle and Barrie didn’t quite connect. For months, they batted the plot back and forth. The music hinged upon the libretto, the libretto depended upon the story line, and the story continued to evolve nearly to opening night, 13 May 1893.

The opening tanked. The authors weren’t asked to ascend the stage for a curtain call. In response, Barrie and Doyle churned out changes, but the die was cast. After fifty performances, the play closed 1 July 1893. (Another source claims the play ran March through April of 1893 for a total of fifty performances.)

Jane Annie became the Savoy’s first flop. Most contemporary sources conclude the play was a failure, but that’s not quite accurate. The play had a strong cast and the company went on tour for another two months in Bradford, Newcastle, Manchester, and Birmingham, where it proved to be considerably more popular. Nonetheless, the London response determined the fate of the show.

Fortunately, Barrie’s and Doyle’s friendship remained intact, and they treated their venture on the stage with humour. Barrie even joked about it with a Holmes parody. Inside the flyleaf of Barrie’s short story collection, A Window in Thrums, he wrote “The Adventure of the Two Collaborators” and presented it to his friend, Doyle.

Without allegorical context, this little story appears to be an awful Sherlock Holmes pastiche, but with the background of the play, we can understand this rueful exchange between two professionals who happened to be best of friends. Note that Barrie hints at the demise of Sherlock, which would take place later that year at Reichenbach Falls in The Final Problem.

The public would remain unaware of this small exchange between writers until 1923 when Doyle wrote an essay for Colliers Weekly, “The Truth About Sherlock Holmes.” At its end, Doyle presents J. M. Barrie’s "The Adventure of the Two Collaborators". Doyle published the parody again in his 1924 autobiography Memories and Adventures.

The Adventure of the Two Collaborators

by Sir James Matthew Barrie

In bringing to a close the adventures of my friend Sherlock Holmes, I am perforce reminded that he never, save on the occasion which, as you will now hear, brought his singular career to an end, consented to act in any mystery which was concerned with persons who made a livelihood by their pen. “I am not particular about the people I mix among for business purposes,” he would say, “but at literary characters I draw the line.”

We were in our rooms in Baker Street one evening. I was (I remember) by the centre table writing out “The Adventure of the Man Without a Cork Leg” (which had so puzzled the Royal Society and all the other scientific bodies of Europe), and Holmes was amusing himself with a little revolver practice. It was his custom of a summer evening to fire round my head, just shaving my face, until he had made a photograph of me on the opposite wall, and it is a slight proof of his skill that many of these portraits in pistol shots are considered admirable likenesses.

I happened to look out of the window, and perceiving two gentlemen advancing rapidly along Baker Street asked him who they were. He immediately lit his pipe, and, twisting himself on a chair into the figure 8, replied:

“They are two collaborators in comic opera, and their play has not been a triumph.”

I sprang from my chair to the ceiling in amazement, and he then explained:

“My dear Watson, they are obviously men who follow some low calling. That much even you should be able to read in their faces. Those little pieces of blue paper which they fling angrily from them are Durrant’s Press Notices. Of these they have obviously hundreds about their person (see how their pockets bulge). They would not dance on them if they were pleasant reading.”

I again sprang to the ceiling (which is much dented), and shouted: “Amazing! But they may be mere authors.”

“No,” said Holmes, “for mere authors only get one press notice a week. Only criminals, dramatists and actors get them by the hundred.”

“Then they may be actors.”

“No, actors would come in a carriage.”

“Can you tell me anything else about them?”

“A great deal. From the mud on the boots of the tall one I perceive that he comes from South Norwood. The other is as obviously a Scotch author.”

“How can you tell that?

“He is carrying in his pocket a book called (I clearly see) ‘Auld Licht Something.’ Would any one but the author be likely to carry about a book with such a title?”

I had to confess that this was improbable.

It was now evident that the two men (if such they can be called) were seeking our lodgings. I have said (often) that my friend Holmes seldom gave way to emotion of any kind, buy he now turned livid with passion. Presently this gave place to a strange look of triumph.

“Watson,” he said, “that big fellow has for years taken the credit for my most remarkable doings, but at last I have him - at last!”

Up I went to the ceiling, and when I returned the strangers were in the room.

“I perceive, gentlemen,” said Mr. Sherlock Holmes, “that you are at present afflicted by an extraordinary novelty.”

The handsomer of our visitors asked in amazement how he knew this, but the big one only scowled.

“You forget that you wear a ring on your fourth finger,” replied Mr. Holmes calmly.

I was about to jump to the ceiling when the big brute interposed.

“That Tommy-rot is all very well for the public, Holmes,” said he, “but you can drop it before me. And, Watson, if you go up to the ceiling again I shall make you stay there.”

Here I observed a curious phenomenon. My friend Sherlock Holmes shrank. He became small before my eyes. I looked longingly at the ceiling, but dared not.

“Let us cut the first four pages,” said the big man, “and proceed to business. I want to know why —”

“Allow me,” said Mr. Holmes, with some of his old courage. “You want to know why the public does not go to your opera.”

“Exactly,” said the other ironically, “as you perceive by my shirt stud.” He added more gravely, “And as you can only find out in one way I must insist on your witnessing an entire performance of the piece.”

It was an anxious moment for me. I shuddered, for I knew that if Holmes went I should have to go with him. But my friend had a heart of gold. “Never,” he cried fiercely, “I will do anything for you save that.”

“Your continued existence depends on it,” said the big man menacingly.

“I would rather melt into air,” replied Holmes, proudly taking another chair, “But I can tell you why the public don’t go to your piece without sitting the thing out myself.”

“Why?”

“Because,” replied Holmes calmly, “they prefer to stay away.”

A dead silence followed that extraordinary remark. For a moment the two intruders gazed with awe upon the man who had unravelled their mystery so wonderfully. Then drawing their knives, Holmes grew less and less, until nothing was left save a ring of smoke, which slowly circled to the ceiling.

The last words of great men are often noteworthy. These were the last words of Sherlock Holmes: “Fool, fool! I have kept you in luxury for years. By my help you have ridden extensively in cabs, where no author was ever seen before. Henceforth you will ride in buses!”

The brute sunk into a chair aghast.

The other author did not turn a hair.

To A. Conan Doyle,

from his friend

J. M. Barrie