[The Doctor] gave me the route map: loss of memory, short- and long-term, the disappearance of single words -- simple nouns might be the first to go -- then language itself, along with balance, and soon after, all motor control, and finally the autonomous nervous system. Bon voyage!

Atonement: A Novel

Ian McEwan

Over the holidays I read several mystery novels, each set in Florida or the Gulf Coast, all in a row. I don’t know why I did this -- maybe the gray skies over Washington, D.C. and the promise (threat?) of more winter on the horizon had something to do with it, or maybe it was just a simple reaction to my impending return to SleuthSayers and the prospect of sharing space on a new day with my friend and inveterate Floridian Leigh. More on those Florida books later -- perhaps next month.

But after that steady southern diet I started to feel a little swampy, which led me to Ian McEwan’s Atonement in search of something different. A great book, by the way. And in it the above quote, from an author character who, near the end of Atonement, confronts the onset of dementia, struck a chord. Confronting and dealing with dementia in the context of mystery novels has been a recurring theme, both lately and historically.

But after that steady southern diet I started to feel a little swampy, which led me to Ian McEwan’s Atonement in search of something different. A great book, by the way. And in it the above quote, from an author character who, near the end of Atonement, confronts the onset of dementia, struck a chord. Confronting and dealing with dementia in the context of mystery novels has been a recurring theme, both lately and historically.

In an earlier article discussing first person narration I referenced Alice LaPlante’s debut novel Turn of Mind, where the central character and first person narrator, Dr. Jennifer White, is an Orthopedic surgeon suffering from Alzheimer's disease. LaPlante skillfully allows the reader to know only what Jennifer knows, and the story progresses only through her distorted view. As readers we are imprisoned in her mind, a mind that Dr. White herself describes as:

This half state. Life in the shadows. As the neurofibrillary tangles proliferate, as the neuritic plaques harden, as synapses cease to fire and my mind rots out, I remain aware. An unanesthetized patient.

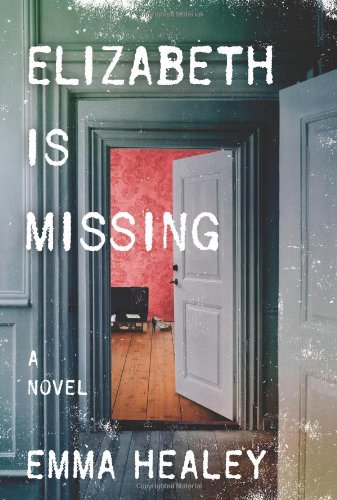

Another recent mystery utilizing the same technique -- a narrator disabled by dementia -- is Emma Healing’s ambitious mystery Elizabeth Is Missing. Here, too, the first person narration is by the central character, Maude, who speaks through her dementia, and all we know of the mystery at hand, and the clues to its solution, are told to us through her filter.

Tough stuff, writing a mystery under such constraints. But what about the tougher task -- writing a mystery when it is the author who is struggling with the real-life constraint? That may be precisely what Agatha Christie did when she penned her last mysteries.

I began to read Christie late, after I had exhausted all of the Ellery Queen mysteries that were out there. And that early obsession with Queen tripped me up a bit as I approached Christie. With Queen I found that I liked the later mysteries best, those from the mid-1940s on. I particularly liked the final Queen volumes, beginning with The Finishing Stroke. And that led me to a mis-step. I began reading Christie by starting with her most recent works, specifically, Postern of Fate and Elephants Can Remember. Oops.

Postern of Fate, the chronologically last book that Christie wrote, features Tommy and Tuppence Beresford. This, on its own, is a sad way to end things -- they were hardly Christie’s best detective characters. But that is not the real problem. The reader uncomfortably notes from the beginning of the book that conversations occurring in one chapter are forgotten in the next. Deductions that are relatively simple are drawn out through the course of many pages. Clues are dealt with multiple times in some instances, in others they are completely ignored. The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English, tags the work as one of Christie’s "execrable last novels" in which she "loses her grip altogether."

Elephants Can Remember, written one year earlier, fares no better. The Cambridge Guide also ranks this as one of the “execrable last novels.” More specifically, English crime writer, critic and lecturer Robert Bernard had this to say:

Another murder-in-the-past case, with nobody able to remember anything clearly, including, alas, the author. At one time we are told that General Ravenscroft and his wife (the dead pair) were respectively sixty and thirty-five; later we are told he had fallen in love with his wife's twin sister 'as a young man'. The murder/suicide is once said to have taken place ten to twelve years before, elsewhere fifteen, or twenty. Acres of meandering conversations, hundreds of speeches beginning with 'Well, …' That sort of thing may happen in life, but one doesn't want to read it.

Speaking of reading, are we perhaps reading too much into all of this? Could it just be that Christie had run out of inspiration? Younger writers (Stephen King comes to mind) display peaks and valleys in their fiction output. Could Christie have just ended in a valley? Unlikely. There is almost certainly more to Christie’s problem than just un-inspired plots.

Ian Lancashire, an English professor at the University of Toronto wondered about the perceived decline in Christie’s later novels and devised a way to put them to the test. Lancashire developed a computer program that tabulates word usage in books, and then fed sixteen of Agatha Christie’s works, written over fifty years, into the computer. Here are his findings, couched in terms of his analysis of Elephants Can Remember, and as summarized by RadioLab columnist Robert Krulwich:

When Lancashire looked at the results for [Elephants Can Remember], written when [Christie] was 81 years old, he saw something strange. Her use of words like "thing," "anything," "something," "nothing" – terms that Lancashire classifies as "indefinite words" – spiked. At the same time, [the] number of different words she used dropped by 20 percent. "That is astounding," says Lancashire, "that is one-fifth of her vocabulary lost."

But to her credit, Christie was likely battling mightily to produce Elephants and Postern. Lancaster hypothesizes as much, not only from the results of his computer analysis of vocabulary, but also based on a more subjective analysis of the plot of Elephants.

Lancashire told Canadian current affairs magazine Macleans that the title of the novel, a tweaking of the proverb "elephants never forget", also gives a clue that Christie was defensive about her declining mental powers. . . . [T]he protagonist [in the story] is unable to solve the mystery herself, and is forced to call on the aid of Hercule Poirot.

"[This] reveals an author responding to something she feels is happening but cannot do anything about," he said. "It's almost as if the crime is not the double-murder-suicide, the crime is dementia."

In any event Christie likely should have stopped while the stopping was good, which she did after Postern. Her final mysteries, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, while published in the mid-1970s, were in fact written in the 1940s.

Christie’s plight is a bit uncomfortable for aging authors (I find myself standing in the queue) to contemplate. But thankfully Christie’s road as she reached 80 is not everyone’s. Rex Stout still had the literary dash at about the same age to give us Nero Wolfe slamming that door in J. Edgar Hoover’s face in The Doorbell Rang. There, and in his final work Family Affair, written in 1975 when Stout was in his late 80s, there are certainly no apparent problems. Time’s review of Family concluded "even veteran aficionados will be hypnotized by this witty, complex mystery." I recently read Ruth Rendell’s latest work, The Girl Next Door, written during Rendell's 84th year, and it is, to use Dicken’s phrase, “tight as a drum.” Similarly, the last P. D. James work, Death Comes to Pemberley, a Jane Austen pastiche written when James was well into her 90s, received glowing reviews, most notably from the New York Times, and has already been adapted into a British television miniseries. And when James’ works were analyzed by the same computer program to which Christie’s novels were subjected, the results established that James’ vocabulary, even in her 90s, was indistinguishable from that employed in her earlier works.

So if you are both writing and contemplating the other side of middle age, watch out! But on the other hand don’t needlessly descend into gloom. Keep your fingers crossed and remember the advice of Spock, as rendered by Leonard Nimoy (also in his 80’s): Live long and prosper!

.jpg)