I’ve spent the last year working on a nonfiction ghostwriting project for a client who got a deal to deliver a memoir about, shall we say, his military career. (Our contract precludes me from spilling many of the details, but I’ll try to work around it.)

Recently, I asked the client a question that puzzled even him.

“Did you return home at any point during your first deployment?”

“No, why?”

“Because your first daughter had to have been conceived during that year. If you were overseas…”

I stopped shy of asking him who the father really was…

A few days later I got a flurry of humorous texts from his wife. They both had a good laugh over my question. Yes, she recalled, he did come home once during that period of time. (She had photos of a romantic dinner and getaway weekend to prove it. Not that I needed it!) By the time Dad returned home again, a beautiful three-month-old baby was waiting to greet her father for the first time.

“That’s so funny,” the wife told me. “It was so long ago, we forgot that little detail. How did you figure it out?”

Normally, I can use these moments to brag that I’m the greatest reporter ever. But in this case, the tipoff sprung not from my brain but from a piece of software that I’ve been using to plot the book.

The software is Aeon Timeline. Product developers use it to plot the trajectory of their real-life projects. Scholars and historians use it to map out their areas of study, both Before Common Era (BCE) and Common Era (CE). Lawyers use it to plot litigation strategies and timelines. Writers of all stripes use it to map out fiction and nonfiction. Screenwriters presumably can do the same.

This is not the world’s most expensive software. You’ve got it forever for $65. If you want annual updates, that will run you a little extra. All completely tax deductible for a professional writer.

What do I like about the program? I can list every single character in the book I’m planning, inserting their birth and death dates. From that moment forward, whenever Character A meets Character B in the timeline, the software automatically calculates each person’s age down to the years, months, and days. For the project I’m working on now, I can insert real-life historic events—the election of presidents, dates of wars, what-have-you—and everything will populate on my screen, showing me how people, places, events all intersect.

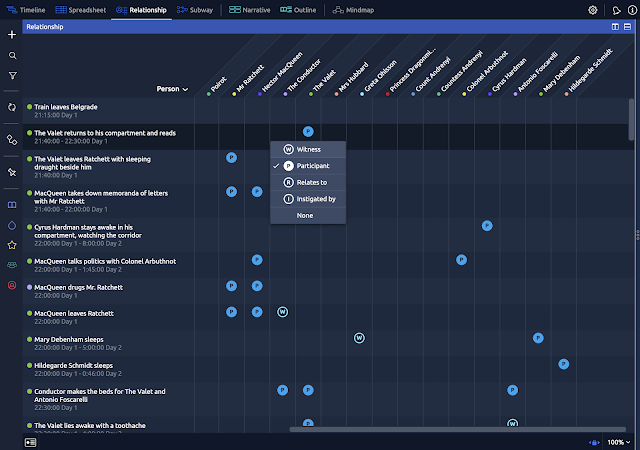

As you can imagine, this can be pretty useful for mystery writers working with tricky timelines. On its website, Aeon actually uses Murder on the Orient Express as one of their case studies. (I have reproduced some of the Orient Express screenshots here, but you will find them infinitely more readable on this page of Aeon’s website.)

That novel is a good example because everything hinges on the events occurring over one night aboard that infamous train. Poirot nimbly tucks away all the details in his little gray cells, but I’m pretty sure Dama Agatha plotted her story using a handwritten version of what Aeon shows us in these screenshots.

If you need to keep track of murder weapons, locations, character traits, etc., you can easily create a new entry and start tracking that plot point or detail.

I guess you could say the software is remarkably flexible. I like that about Aeon Timeline. I also sorta kinda hate it. This is one of those software programs that rewards a long learning curve. Luckily, there is a knowledge base, forum, and developer support on the software’s website, not to mention countless YouTube videos to help you piece together how to use it.

Early on in this project, I found myself spending a tedious week trying to input all our nonfiction milestones into the software. I pulled the details from a mountain of documents the client shared with me. Four or five days into this, I had to ask myself if this was all worth it. Was I wasting my time? Couldn’t I just hand-write the details on sheets of paper, the way I’d always done?

I could have, but then I would have had to keep a mountain of paper at the ready. Instead, once I input everything into the program, I tucked the reams of paper into a banker box, forgot about them, and focused on the unfolding story instead. Every time I did another interview with the client, I spent a few post-call minutes plugging new dates and times into the program.

Aeon has been a lifesaver, and I’m eager to try it again for an upcoming fiction project. I think you’d get the best mileage out of Aeon using it to plot longer projects such as novels, novellas, or anthology book series. One feature I’m eager to try is Aeon’s narrative timeline, which allows you to drag and drop plot points from one timeline into a secondary timeline that mimics how you will actually structure the book.

Example: A scene actually occurs at the end of the timeline, but you can drag it into the prologue position. That could be a valuable feature if you were planning a project with an abundance of flashbacks.

All that said, Aeon might be helpful if you’re writing a short story of unusual complexity. Since my short stories tend to be, ahem, fairly clueless, I don’t think it would be smart to plot them digitally. Most of the time, a sheet of scrap paper with a five or so plot points is enough to keep track of where I’m going. And besides, I enjoy writing short stories precisely because dense outlines aren’t necessary.

It may not look like it, but I really do try to limit the amount of software I use in my daily work. If something doesn’t blow me away with its usefulness, I chalk the whole thing up to an experiment that didn’t pan out, and delete the program from my computer. Because, in the end, who really has the time?

I’ll discuss another software program for writers when I see you in three weeks!

Joe

josephdagnese.com