[A] pastiche is a serious and sincere imitation in the exact manner of the original author.

-- Ellery Queen

The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes (1944)

We have been using the word "pastiche" for decades, at least since Ellery Queen's The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes, a collection of such stories, was published in 1944.

-- Chris Redmond

"You Say Fanfic, I Say Pastiche -- Is there a

Difference?” (2015)

Difference?” (2015)

This week (I am happy to announce) marks the culmination of a project that has kept me fairly busy for a good bit of the last year -- the publication of The Misadventures of Ellery Queen, co-edited by Josh Pachter and me, Dale Andrews. The anthology collects, for the first time, 16 stories, written over the course of some 70 years. The stories are “misadventures,” that is, pastiches, parodies and other homages, all inspired by author/detective Ellery Queen. For Josh and me putting together this collection has been a work of love. And it has also been a project that has been, well . . a long time coming.

Many of you may remember from previous SleuthSayer articles that Ellery occupies a particularly warm spot in my writing heart. Over the years I’ve written three Ellery Queen pastiches that have graced the pages of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and I’ve written numerous articles on Ellery and his exploits that have appeared on SleuthSayers. While some of the backstory to The Misadventures of Ellery Queen predates SleuthSayers, the recent story of how the collection came into being can be traced through various footprints throughout the history of this website.

Books collecting “misadventure,” that is, anthologies that carry forth the exploits of an established character but in stories penned by other authors, have a long pedigree. The best examples of misadventures are the many stories and anthologies offering up new Sherlock Holmes stories written outside of the established Arthur Conan Doyle canon. And the first collection of such stories was The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes, edited by none other than -- Ellery Queen in 1944. (The collection was quickly withdrawn from the public following a copyright challenge from the Arthur Conan Doyle estate. Luckily for all of us the collection is now once again readily available.)

It was only natural that a fan of Ellery Queen who has also written new Ellery Queen adventures (that would be me!) would reasonably be expected to ponder why the stories not originally drafted by Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee but nonetheless featuring their detective creation Ellery have not been previously collected. EQ pastiches and parodies are not as numerous as those featuring Sherlock Holmes, but nevertheless many have popped up with some regularity since at least 1947, when Thomas Narcejac wrote (in French) Le Mystere de ballons rouge featuring Ellery, and the inspector. Since then Jon L. Breen, Francis Nevins, Edward D. Hoch and a host of others, both famous and lesser known, have also contributed Ellery Queen stories. So wouldn’t an Ellery Queen “misadventures” anthology make some sense?

| The Japanese Misadventures |

From 2012 on my author’s copy of the Japanese Misadventures just sat there on my own book case -- staring at me accusingly as nothing happened and the years slipped by. Since I don’t read Japanese about the only thing I could meaningfully ponder in Iiki Yusan’s Misadventures was the list of contributing authors, which appeared in English at the back of the book. The list included the likes of Francis Nevins, Jon Breen, Ed Hoch, and even me.

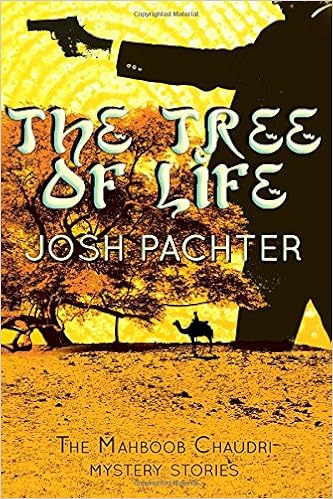

Also a guy named Josh Pachter.

Josh Pachter? Back in 2011 when I wrote that first SleuthSayers column the name meant nothing to me.

Josh, it turned out, has written many mystery stories during a career of almost fifty years -- including several homages featuring a character by the name of E.Q. Griffen. The reason I was unfamiliar with these stories is the same reason that I had concluded that we needed a collection of Ellery’s misadventures -- Josh’s Ellery Queen homages were nearly impossible to find. Like almost all EQ pastiches, parodies and homages they were published originally in issues of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and that had occurred many years ago. As a practical matter those magazine issues were unavailable to the vast majority of the reading public. But even given this, I began to hear more and more about Josh, including the fact that he lived not all that far away from me, outside of Washington, D.C. in the Virginia suburbs.

So let's skip a few years and eventually alight in yet another SleuthSayers article.

In the summer of 2015 I received an email from my friend Francis (Mike) Nevins informing me that he would be traveling through Washington, D.C. that September. I immediately offered up our guest room, and Mike accepted.

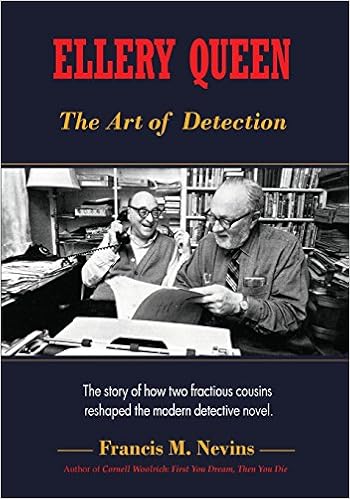

Mike Nevins, as many of you will know, is an emeritus professor at St. Louis University Law School, a preeminent Ellery Queen scholar and the author of many short stories and books, including two seminal biographical works chronicling the lives and works of the two cousins who were Ellery Queen -- Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee: Royal Bloodline: Ellery Queen, Author and Detective (1974) and the more recent Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection (2013). Mike’s 2013 book was, in fact, reviewed by me right here on SleuthSayers in January of 2013.

Mike is also the author of one of the finest Ellery Queen pastiches ever written -- “Open Letter to Survivors.”

When Mike accepted my invitation by return email he told me that he would really like to get together with an old friend during his D.C. stay. Another author. Named Josh Pachter. As I said, by then I knew who Josh was. Mike and I contacted Josh by email and dinner was scheduled for a September evening in the backyard of my home. The dinner (you guessed it) was the subject of my SleuthSayers article of September 27, 2015.

|

| Josh, Mike and me in the backyard. (Animation courtesy of Google!) |

It didn’t take long for the gears to begin to mesh. Maybe each of us thought. Just maybe working together we could actually do this.

And, to make a longer story short, we did! The Misadventures of Ellery Queen, which we compiled over the course of almost a year, has one story by each of us -- “The Book Case” for me; “E.Q. Griffen Earns his Name” for Josh. The other 14 stories are by other authors. We had a lot of stories to choose from, and the final volume differs in many respects from the Japanese Misadventures anthology. Our book includes the first ever English translation of that 1947 Thomas Narcejac pastiche “The Mystery of the Red Balloons,” as well as Mike Nevin’s “Open Letter to Survivors.” Readers will also find Jon Breen’s pastiche “The Gilbert and Sullivan Clue,” and a particularly sneaky pastiche by Ed Hoch, which spent most of its literary life masquerading as an Ellery Queen-authored story . There are stories by Lawrence Block. William Brittain, James Holding and others. And the book also includes what is probably the most recent Queen homage (a sort of pastiche with it’s own twist) Edgar winner Joe Goodrich’s “The Ten-Cent Murder.” All of those, and quite a few others by authors famous and authors obscure share one thing in comon -- each was inspired by Ellery.

Josh and I are particularly pleased with the final product shaped by our publisher, Wildside Press, which has made the collection available in hard cover, trade paperback, and Kindle editions.

| Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee Picture courtesy of "Ellery Queen -- A website on Deduction" |

Choosing the stories, writing introductions, and otherwise putting this volume together has been a joy for Josh and me for many reasons. Perhaps the greatest joy is mirrored in an observation by Janet Hutchings, editor of EQMM. In these Misadventures, she has written, “Ellery Queen lives again.” That's what we were hoping for. Dannay and Lee, writing as Ellery Queen observed in their introduction to that 1944 Sherlock Holmes Misadventure anthology that pastiches and parodies are "the next best thing to new stories."

And that was always what we wanted most to accomplish -- bringing some of the many adventures of Ellery Queen written by authors other than Dannay and Lee together in one volume. We hope that readers will enjoy diving into these alternative adventures as much as we have enjoyed collecting them.

One final note -- in addition to availability on-line, The Misadventures of Ellery Queen will also be on sale at the Malice Domestic convention at the end of April. And Josh and I will both be there. Just in case anyone might want . . . uhh . . . a signed copy?

One final note -- in addition to availability on-line, The Misadventures of Ellery Queen will also be on sale at the Malice Domestic convention at the end of April. And Josh and I will both be there. Just in case anyone might want . . . uhh . . . a signed copy?

.jpg)