Rule 59 Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide (1908)

|

| Washington Nationals' Spring Training, Viera, Florida |

During the winter, when baseball retreats with the sun, I try to fill the void with the next best thing. There are others out there like me, and this usually inspires an annual crop of baseball books, generally published during the winter of our discontent. I have highlighted such books in past March columns here and here, and this year the best of the annual lot may be Where Nobody Knows Your Name by John Feinstein. Feinstein’s book is a non-fiction account of what it is like to play in the minor leagues -- far from the chartered jets and mega-salaries. The book is populated by has-beens and wannabees, and, as a result, in its telling it imparts a wistful sadness that can be found at times in baseball stories.

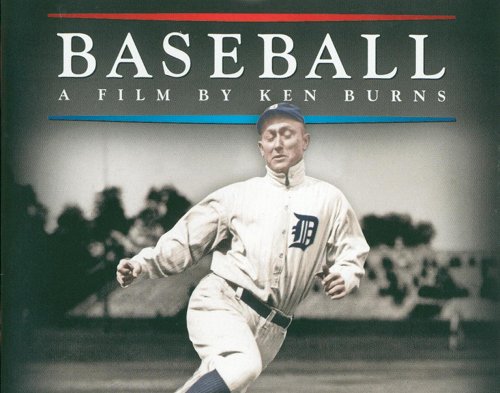

This year I also sought solace watching Ken Burns excellent Baseball documentary, originally released on PBS in nine episodes in 1994 and subsequently updated and expanded to ten episodes (innings) in 2010. The full series, available on-line from NetFlix, and elsewhere in DVD format, is highly recommended. Burns is a master, and his homage to the national pastime regales the viewer with the stories behind the sport. And like John Feinstein’s new book, Burns, too, offers some poignant stories amidst the heroics. A good example is the story of Fred “Bonehead” Merkle, which goes back over one hundred years.

In 1908 Merkle was a 19 year old backup first baseman on the New York Giants, a team that that year was in a neck-and-neck race with the Chicago Cubs for the pennant. Merkle had received high praise as an up and coming backup player when in late September the fates interceded. What started the ball rolling (or flying) could have been a big break for Merkle, but, as described by the Sports Encyclopedia in 2001, it didn’t turn out that way.

Fred Tenney [the Giants’ regular first baseman] woke upon September 23rd (1908) in the throes of a lumbago attack, and 19-year-old substitute Fred Merkle was sent in to take his place at first base. As events turned out, fate would treat Merkle unkindly that day.

Merkle took his position at first base and all went well until the bottom of the ninth inning when Merkle stepped up to the plate. The score was tied, one to one, and there were two outs. Merkle’s teammate Moose McCormick (what a great baseball name!) was on first base. Merkle singled and McCormick advanced to third. The next batter, Al Bridwell, also singled. Moose McCormick trotted home and the stadium erupted, fans storming the field in celebration of the Giants’ apparent win.

|

| The field just after Moose trotted home |

Concluding that the game was over, and perhaps a little terrified by the stampeding crowd, Fred Merkle lit out for the Giants clubhouse. But, unfortunately for him and for the Giants, he did this without first tagging second base. The Cubs second baseman, Johnny Evers, noticed this and, with Rule 59 (quoted above) buzzing around in the back of his brain, Evers had an Epiphany moment. He started jumping up and down, frantically screaming for his teammates to throw him the baseball, which he realized was still technically in play. In response a ball was retrieved by the Cubs, thrown to Evers, and Evers tagged second, while continuing to jump up and down to attract the attention of the umpires.

It took the umpires and the review process two days to sort out the mess, and they eventually ruled that because Fred Merkle had not tagged second Rule 59 dictated that that when the ball was thrown to second base Merkle was out and that, under Rule 59, the otherwise winning run was negated. This left the game a tie. A makeup game was therefore scheduled for October 8. The Cubs won that game, and as a result the pennant, by a score of four to two.

The Giants manager, John McGraw, was furious at the decision, and later handed out gold medals to all of the members of the Giants team proclaiming them the true champions, despite the fact that the Cubs went on to win the 1908 World Series. Were the Giants “robbed” of the pennant? Well, it all depends on exactly what happened to that baseball between the time that Al Bidwell hit it and the moment some minutes later when Evers was seen jumping up and down on second base with a baseball in his hand.

The story, as told in the Ken Burns series, went like this: When Johnny Evers realized that Merkle had returned to the dugout without tagging second he frantically signaled his teammates to retrieve the ball. Seeing what was going on Giants coach Joe McGinnity tried to prevent the play at second. As the Cubs players raced toward him he scooped up the ball and tossed it into the stands where it was caught by a fan wearing a bowler hat. Two Cubs players then sprinted into the stands, wrestled the ball from the hands of the fan, and relayed it to Johnny Evers at second base for the out.

If Burns got it right the play was pretty spooky but it is hard to say how the Giants were “robbed” -- the out was made consistent with the requirements of Rule 59. However the previous sentence begins with a mighty big “if”. The accounts of what happened that day vary radically and, rather strangely, it is almost impossible to find the account that Burns tells in his documentary. By contrast, here is the eyewitness account of what transpired as recorded by Mr. O. C. Schwartz in a diary that was discovered over 70 years later among Mr. Schwartz’s effects at an estate sale.

So much has been said about what is commonly called "The Merkle Boner" that, being an eyewitness to the account, I should set the matter straight once and for all.

It was a Wednesday, Sept. 23 in 1908, my Dad took me to the game , letting me miss school that day. I was only eight-years old at the time, and it was the first chance I ever had to watch a professional baseball game in person.

I may be 75 years old, but I remember it as if it were yesterday.

The controversy is all about what happened in the bottom of the ninth inning. The Polo Grounds was crowded that day. The fans were all getting ready to rush the field at game's end.

The score was tied 1-1 with two outs. A fellow by the name of McCormick was on first base at the time. Fred Merkle came to bat and wasted no time getting a base hit and advancing the runner to third base.

The crowd was absolutely hysterical as Al Bridwell came to the plate. Bridwell singled to the outfield and McCormick scored what was the apparent winning run. The fans all rushed onto the field to celebrate the win as pandemonium filled the ballpark.

It is a funny thing, but instead of watching all the people or the players, I kept my eye on the ball. It came to center fielder Solly Hofman on the second bounce. Realizing that the winning run was scoring as he fielded the ball, Hofman lobbed a rainbow into the infield. The third base coach Joe McGinnity, pitcher Christy Mathewson and a fan were all in a battle with second baseman Johnny Evers to catch the ball. After a brief skirmish, the fan came away with the ball and heaved it into the stands along the third base line.

Meanwhile Merkle, who was so excited by his team apparently winning the game, jogged halfway to second base and then starting running towards the Giant's dugout. Mathewson or one of the other Giants in the dugout had yelled to Merkle and he began scurrying towards second base.

Evers had somehow retrieved yet another ball from somewhere and touched second base ahead of Merkle and the umpire, at Evers admonishing, saw the event and ruled Merkle out, thus negating the winning run.

So much has been said and talked about over the decades, about whether Evers had the ball that was hit by Bridwell. I saw it with my own eyes, Evers forced Merkle out at second with a ball which was thrown to him from the New York dugout.

The chaos that ensued was one of the wildest things I have ever seen. The umpires were arguing with Cubs manager Frank Chance and Giants manager John McGraw in the infield. After being swarmed by fans and reporters, the umpires decided to assemble in the umpires quarters which was located behind home plate beneath the grandstand.

After deliberating what seemed like an eternity, they came back to the field and advised everyone of their decision. They had decided that the force-out at second base negated the run scored, therefore the game ended in a tie, and would have to be replayed, pending a review by the National League President.

If I forget everything else in my life, I shall never forget the look of sadness and helplessness in the face of young Fred Merkle right then.

If Mr. Schwartz got it right, it was, indeed, robbery that sent Chicago on the road to the pennant and world series in 1908. After winning the World Series in 1908 the Cubs never again reached that prize, and now hold the dubious distinction of being the team with the longest World Series drought in the history of the sport. Some say this Cubbies curse began in 1945, when owner P.K. Wrigley ejected Billy Sianis, a Chicago tavern owner who had come to Game 4 with two box seat tickets, one for him and one for his goat. But others count that curse as having begun the day that the Cubs, through what may well have been sleight of hand, manufactured an out at the expense of Fred Merkle and the New York Giants.

|

| A cartoon depiction with its own boner -- Fred in a Cubs cap! |

But fair or not, there is no two ways about it -- the whole mess would have never occurred if Fred had just tagged second. The Giants manager, McGraw, was steadfast in not blaming Merkle. Most everyone else, however, was not that charitable. Merkle played with a succession of teams through 1920, but always under the spectre of that blunder he committed when he was nineteen. By all accounts the blunder stalked him the rest of his life. The following is by Keith Olbermann, writing in Sports Illustrated:

It was nearly 30 years after the game—that game—and, Marianne Merkle remembered, even church wasn't a safe haven. One Sunday morning in the 1930s, Merkle and her family were attending services in Florida, when a visiting minister introduced himself. "You don't know me," he piped, "but you know where I'm from! Toledo, Ohio! The hometown of Bonehead Fred Merkle!"

Little Marianne knew what would happen next. "The kindness drained from [my father's] face," she told me five decades later. Then Fred Merkle rose and wearily told his wife and daughters, "Let's go."