|

| Louis XIV, in his glory |

Years ago, I used to teach a class on the Age of Louis XIV, which basically became a class on the man himself. He may or may not have said "L'etat, c'est moi" ("I am the state), but he certainly lived it. He was the first, and greatest, of the absolute monarchs of post-Reformation Europe, and during much of his 72 year reign, if someone -

anywhere in Europe, not just France - said something about "the King", it was assumed they meant Louis.

Louis XIV (1638-1715) became king when he was five years old. Of course, they didn't let him actually

rule at that age - he had a minister, Cardinal Mazarin. (Suspected by some of being his mother's lover and/or husband. But not by me: Anne of Austria was a true European aristocrat, who would sooner have eaten

merde as have anything physical to do with a jumped-up Italian.) Mazarin, according to Louis XIV, kept him living in poverty, barely educated. It could be true.

NOTE: Children, even royal children, weren't as prized back in the day as they are now. Classic example, Charles Maurice Talleyrand-Perigord, the eldest son of his house, who was put out to nurse in the countryside for his first few years. He returned lame. His parents then made his younger brother the heir, and put our boy into the Church, where he became the most dissolute, loose-living, atheistic Bishop of Autun since... who knows when. (Eventually, he joined the French Revolution, managed to switch sides with such persistent effectiveness that he survived everything, from the Reign of Terror to Napoleon to the Bourbon Restoration...)

SECOND NOTE: Louis XIV's only sibling, his younger brother Philippe, who was universally called Monsieur, had a VERY interesting upbringing. He was deliberately raised to be a homosexual, or at the very least a transvestite; his mother and her ladies encouraged him to dress up in women's clothing, make-up, jewelry and hairstyles. He was deliberately kept from any formal education other than the 3 r's, and any knowledge of statecraft. All of these were so that he'd never be a rival for his brother. The result was a man who was bisexual, surprisingly martial, and through his two marriages, became the "grandfather of Europe", ancestor of every Roman Catholic royal house in Europe. You never know...

Back to Louis, who would have been infuriated by that digression. Louis' childhood influenced him in many ways, but it was the Fronde (1648-1653) that created his ruling style. The Fronde was a multiplicity of rebellions that had no order, rhyme, or reason to any of it. Of, by, and for the nobility, the Fronde's goal was to return to the good old days when a nobleman could rule his lands and provinces as a petty king, with absolute power. And there had been no jumped-up clergymen (Richelieu and Mazarin) to try and make them knuckle under to some Bourbon king.

NOTE: Part of the problem was that in class-ridden pre-modern Europe, the Bourbons weren't that old a family. One of Louis' mistresses, Madame de Montespan, often bragged to his face that her family, the House of Rochechouart was MUCH older than his, and it was. Hers went back to the 800s; his only to the 1200s.

|

Episode of the Fronde at the Faubourg Saint-Antoine by the Walls of the Bastille

(i.e., when the royal family had to flee Paris. See below) |

The Fronde failed, because they really had no goal, no organization, no leadership, and kept bickering. But Louis would never forget it. At one point the Fronde made the whole royal family flee Paris, which was probably THE major humiliation of Louis' life. He decided that the nobility was untrustworthy, Paris was rotten, and came up with the following maxims of government:

- The nobility will have no role in government at all.

- All non-military government roles, positions, and titles will be given to the bourgeoisie (that way, Louis can fire them whenever he wants).

- Parlement's only role will be to rubber-stamp his decisions.

- Paris can rot.

- He, Louis XIV, will rule personally, absolutely, with no prime minister, all his life.

Nobody believed any of this. For one thing, Louis, who was always a master of etiquette, waited politely until after Mazarin's death in 1661 to take the reins of power. And by then there had been 50 years of Prime Ministers ruling France while the kings played. Louis played, and he played hard - but he also did exactly what he said he would.

And the key to doing that, successfully, was:

- to appoint good bourgeois officers (Jean-Baptist Colbert, Comptroller-General; Michel le Tellier, and his son, Louvois, both Ministers of War and Chancellor, among others).

- to personally work like a horse, non-stop, day in and day out

- to distract the nobility with endless perks, entertainment, prizes, all dependent upon HIS favor.

Welcome to Versailles.

Versailles was the old hunting lodge of Louis XIII, 12 miles south of Paris. Louis XIV loved it, despite the fact that it was in the middle of a swamp. He had it remodeled - in fact, it was being remodeled for his entire reign, and some say that the construction is still on-going - and announced, early on, that Versailles was the seat of government. If you wanted to be close to the king (and who didn't?) you went to Versailles. And everyone who could went.

|

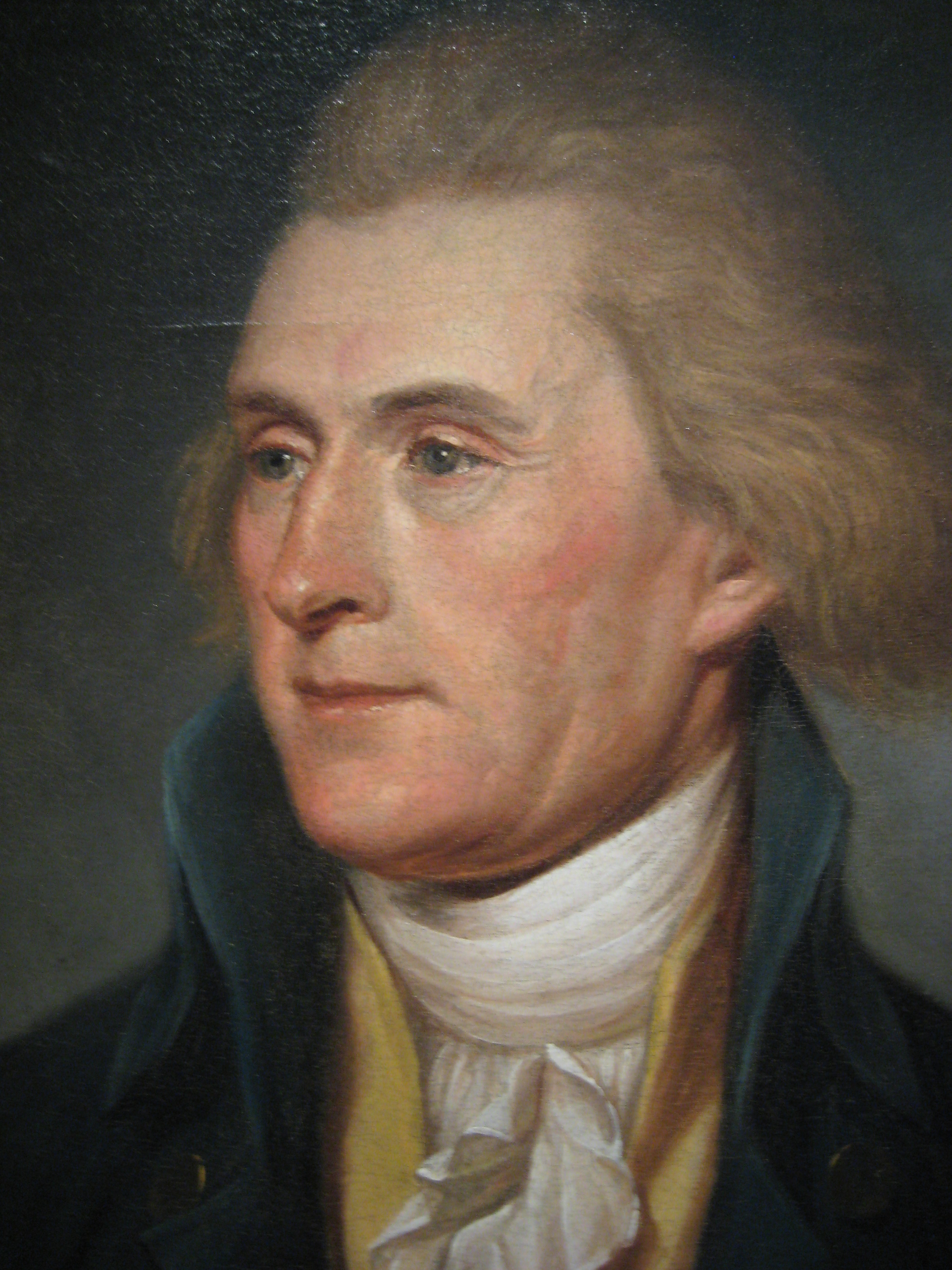

| The Duc de Saint-Simon |

It was a desperately uncomfortable place to live. It was so huge that people could and did get lost in it; only the extremely important people - Louis, his Queen, his mistresses, his endless children, and Monsieur and his wife and children - had beautiful apartments. Most people were crammed into very small rooms, often without windows. The Duc de Saint-Simon, the most celebrated diarist of the period, had three small rooms, one looking out the stables (which stank), the other two of which were the size of walk-in closets without have windows. And these were considered the best suite in Versailles.

But things were different then. Comfort, so important to us today, was held in contempt. The mark of a man of quality was "indifference to heat, cold, hunger and thirst." Magnificence was the order of the day. The nobility lived in chateaus that were drafty, cold, smoky, and reeked of human and animal waste (there was no indoor plumbing). But the rooms looked beautiful. The nobility wore velvets and satins and brocades in summer as well as winter, and the clothes always stank because they couldn't be washed, and people generally stank because they didn't bathe, just kept pouring on the perfume. Louis himself just got rubbed down with scented alcohol every day. But by God they looked marvelous.

Versailles almost bankrupted Paris. Louis never went there. He frowned on any nobility who went there. When the court needed a change of air, they went to Fontainebleau and Marly. Paris was ignored. For decades. But their revenge would come in 1789...

Versailles almost bankrupted Louis (although he never admitted it, and burned the receipts)...

Versailles bankrupted the nobility.

- Living at Versailles meant, for one thing, that the country estates (and in France, being noble meant you had a large country estate that supplied you with an income) were managed by someone else, who certainly wasn't going to send you all the money.

- The King expected his nobles to be well-dressed, and the velvets, silks, and satins, with gold and silver embroidery did not come cheap. And he expected to see new outfits for weddings, births, Feast Days, parties, etc. The Duc de Saint-Simon spent 800 louis d'or for new outfits for himself and his wife for the Duc de Bourgogne's wedding - that was equivalent of $96,000.00 in today's money.

- While much of the constant entertainment at Versailles was free (watching Louis was the major entertainment, from his morning rub to his official coucher with the Queen), including hunting, music, plays, concerts, dances, and the usual amount of drink, drugs, and sex (all right, sometimes more than the usual amount) there was also gambling almost every night. They played vingt-et-un, which is blackjack, as well as roulette and dice. (The King preferred billiards. He generally won.) The stakes could run exceedingly high: Madame de Montespan (of the excellent bloodline) lost 3 million francs in one evening.

- You have to have servants, sedans, dogs, horses, hunting equipment, stable rent, bribes, and... let's put it this way, books of the day said that a single man of wealth and nobility should have at least 36 servants, 30 horses, etc.... Of course, if you married, expenses doubled, and if you had children...

So how did the nobility afford all this? They went into debt. And when they were broke, they ran to Louis, who was usually happy to help them out with a little something, enough to keep them in Versailles. He kept them poor and completely dependent on him and his favor. And his favor wasn't given to anyone who wasn't regularly at Versailles, waiting on him, watching him, being present.

And Louis was always present. How he lived his life I do not know. Louis spent his entire day, from 7:45 a.m. to midnight, in public. (We know where he was every second of every day, because he followed a time-table as rigid as that of a German railroad.) He had an iron constitution, an iron will, an iron work ethic, and he was always on stage. He was never alone, even when he was sleeping, using the toilet or having sex. Not only was someone there, there were a lot of people there, perhaps discreetly looking away. (Probably not.) This was rule by King as rock star, the first total celebrity, the first reality TV show. To see him, to be seen by him, to watch him eat, drink, dress, dance, walk, ride, hunt, etc., was everyone's obsession. And it was considered as much of an honor, if not more, to attend him while he was using the bathroom as when he was holding full court.

NOTE: To show how great the obsession with Louis was - and how tough a bird he was - in 1686, he underwent an operation, without anesthesia, on an anal fistula. In public. Amazingly, he survived. Even more amazingly, a huge number of nobles went to the doctor to be checked to see if they had an anal fistula, and those who did boasted about it! Now THAT's toadying.

|

Portrait sculpture of 18th C.

French peasants, by

artist George S. Stuart

Museum of Ventura County |

Louis had a few weaknesses. Women. Food. (He ate like a horse.) But his chief weakness was the pursuit of personal glory (

la gloire) through building (Versailles, Marly), personal magnificence (clothing, furniture, jewels, etc.), his court's constant magnificence, and on war. Endless war.

In case you're wondering, this was an age in which it was assumed, by everyone, that government had nothing to do with and no obligations towards the common people (peasants and artisans, who made up 95% of the population, along with a smattering of merchants), other than to collect taxes from them. The wealthy paid no taxes at all. Neither did the Church.

The peasants paid for everything. They got nothing. Any improvements, in roads, bridges, canals, etc., were paid for either by the goodness of the local lord or a whim on the part of the king. There were no social services, no pensions, no health care, nothing. Peasants worked until they dropped, and then died. Government was there to support the king, the nobility, the Church, and to wage war.

|

William of Orange defeating

Louis XIV at Naarden |

And war was expensive, then as now. Louis XIV fought many wars because everyone knew that that was what powerful kings did: fight and win wars. The trouble is, none of them were winnable, none of them mattered, and Louis himself was a lousy general. He didn't get anything out of them except a tremendous load of debt, a couple of minor victories, and a lot of dead soldiers. He fought three wars alone trying to conquer the Netherlands. He lost every time, and only succeeded in making William of Orange, the prince of the Netherlands, his enemy for life. When William became king of England in 1689 (William was married to Mary, daughter of James II of England, who was booted out during the Glorious Revolution to make room for her - history is so messy...) Anyway, when William became King of England, it meant that England and France would be at almost perpetual war (simmering or boiling) for the next 150 years. Including a couple that involved the American Colonies, The Nine Years War a/k/a King Williams' War (1689-1697), and the War of the Spanish Succession a/k/a Queen Anne's War (1701-1714).

Louis succeeded in what he wanted to do. He kept the nobility powerless and he kept himself absolute monarch for 72 years. But he almost destroyed France in the process. He came to the throne of the most powerful, most populous, most wealthy country in Europe, and left it in debt, surrounded by enemies, crippled by a tax system that, depending as it did entirely on the poor, was so bad that in, 70 years, it would spark a revolution.

Much the same results came from all the absolute monarchs of the 17th and 18th centuries - endless wars, fighting over and over and over again over the same territories, bankrupting entire countries, and leading, finally, to the almost constant revolutions of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The pursuit of war and glory - by leaders who cannot be told "No" - and its results can be summed up by Thomas Gray:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

- Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, 1751