SAN ANTONIO — Texas has seen the future of the public library, and it looks a lot like an Apple Store: Rows of glossy iMacs beckon. iPads mounted on a tangerine-colored bar invite readers. And hundreds of other tablets stand ready for checkout to anyone with a borrowing card.

Associated Press, January 3, 2014

Describing San Antonio’s new “bookless” library

There is no debating the fact that the movement, of late, has been away from the hardcover books that were the staple of the golden age of mysteries. Today much reading (mine included) is on tablets, and our personal libraries (and San Antonio's public library) are composed of texts that are stored in the cloud. But whenever something is gained in technology we run the risk of leaving something valuable behind. We will get to that, but first a little backstory.

Back in September I posted an article titled Herewith, the Clues, which discussed the development of “fair play” mysteries, the hallmark of the “golden age” of detective stories. In that article I summarized the birth of the fair play mystery as follows:

Turns out I wrote that article too soon. I hadn't anticipated the recent publication of “S.” , co-authored by movie and television visionary J.J. Abrams and professor, Penn/Hemmingway nominee and three time Jeopardy champion Doug Dorst. To paraphrase Mr. Abrams' re-boot of the Star Trek series, "S." boldy goes where no fair play mystery has gone before. And make no mistake -- "S." is unapologetically a book in every sense of the word.

To date "S." is available only in hardcover, and if you order it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble you are likely to encounter a “temporarily out of stock” notice. (It took about a week for my volume to arrive from Amazon. "S." is currently listed as out of stock without a delivery estimate at Amazon; Barnes and Noble is projecting shipment no earlier than mid-March). When you do finally get your hands on your own copy of this mystery you will begin to understand why, despite strong interest and positive reviews, sales have out-stripped production by the publisher.

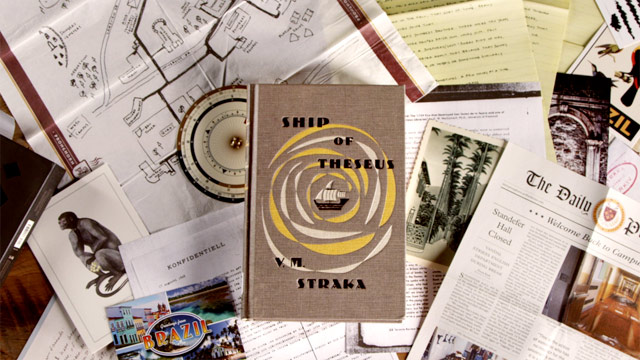

If you order the volume and then wait patiently for delivery, here is what you will eventually hold in your hands -- a handsome cardboard book sleeve containing a hardcover volume, battered and worn, titled Ship of Theseus, purportedly by an author named V.M. Straka. The cardboard box is sealed, and cannot be opened until the paper seal -- the only portion of the book containing the title “S.” -- is broken. Once unsealed, the book presents as a very used library book -- a publication date of 1949, stains on the inside front cover, a “Book for Loan” stamp, a list of check-out stamps on the back inside cover. There is a library index number affixed by sticker on the spine, and the spine itself appears “broken” from frequent opening. When you open the book yourself, it immediately becomes evicent where we, as readers, are headed.

Ship of Theseus is a 453 page novel, complete unto itself. The novel is a good read even standing on its own. But the magic here is that it does not stand on its own. Scribbled throughout all of the pages are notes and annotations by two readers -- Eric, a graduate student who is obsessed with the mysterious Straka, and Jen, a college senior, who has just discovered the author. The premise is that each of them has taken the book from a library shelf, read it, and then returned it to the shelf for the other to re-claim. Eric has initially annotated certain portions in the margin, and Jen responds with her own annotations. Thus begins a dialog that becomes a separate story, sprawling through the pages of Ship of Theseus. In the margins the annotators meet, flirt, and then get down to the task of uncovering the mysteries surrounding Straka and Ship of Theseus, which purportedly was the last of 18 Straka novels (the others are dutifully listed at the front of the book). As if all of this were not enough, as the two annotators discover additional clues or bits of information surrounding the mysterious author, or his equally mysterious translator F. X. Caldeira, they place these snippets of information, or their hand-written summations of what they have uncovered, in the book, at relevant pages, where the reader can extract the clues and follow the evidence at his or her leisure.

And make no mistake -- “leisure” is the right word here. This is a book to be savored, not rushed. In fact, you probably could not rush this book if you wanted to. The reader is called upon to keep track of the underlying Straka novel while, at the same time, following the separate dialog in the margins speculating on the book and the many mysteries surrounding its author. In this respect the book shares some commonality with the underlying theme of Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, discussed at some length in that previous article. The mysterious Stanislas Cordova, who is largely un-seen but occupies the heart of Pessl’s mystery, is eerily similar to the equally-unseen V. M. Straka, who is at the heart of "S.". But back to the point, be prepared to take your time with this book -- you will be rewarded with a near total immersion into the story, a new reading experience that can easily become mesmerizing.

Transforming the concept of the book into a market reality has been a supreme technological challenge, as explained by Abrams in interviews in The New York Times and on CBS. And the problems of the approach continue -- librarians (Rob might like to weigh in here) are perplexed with the challenge of including the book, with all of its loose-leaf clues, on lending shelves, characterizing the task as “a processing nightmare.”

While an ebook version of "S." has been hinted at, it is hard to imagine how this could work. The book, after all, is a throwback -- it is an homage to the published word. In ways it resembles an art book as much as it does a mystery. Could it also be a vanguard? The New York Times had this to say:

Describing San Antonio’s new “bookless” library

There is no debating the fact that the movement, of late, has been away from the hardcover books that were the staple of the golden age of mysteries. Today much reading (mine included) is on tablets, and our personal libraries (and San Antonio's public library) are composed of texts that are stored in the cloud. But whenever something is gained in technology we run the risk of leaving something valuable behind. We will get to that, but first a little backstory.

Back in September I posted an article titled Herewith, the Clues, which discussed the development of “fair play” mysteries, the hallmark of the “golden age” of detective stories. In that article I summarized the birth of the fair play mystery as follows:

An organized approach to writing fair play mysteries dates at least from the 1930s when a number of famous (or soon to be famous) British mystery writers, including Christy, Sayers and Chesterton, to name but three, established the Detection Club with the intention of establishing standards for “fair play” detective stories. Each of the members of the club took the following oath, reportedly still administered today:

Do your promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?

The members of the Detection Club went on to establish rules of fair play that, by and large, have governed the writing of fair play detective stories ever since. The most important of those rules is that every clue necessary to solve the mystery must be revealed, in advance, to the reader.There have been different experiments over the years focusing on how best to lay out all of those clues before the reader, and my prior article went on to discuss various mysteries that have taken the fair play approach to some intriguing extremes. In that vein, the early “Criminal Dossier” works of Dennis Yates Wheatley and James Gluckstein Links, and the recent best-selling Night Film by Marisha Pessl, were singled out as examples of mysteries that literally served up the clues to the readers -- physical evidence, newspaper articles, written reports, all bound within or otherwise contained in the original volume.

Turns out I wrote that article too soon. I hadn't anticipated the recent publication of “S.” , co-authored by movie and television visionary J.J. Abrams and professor, Penn/Hemmingway nominee and three time Jeopardy champion Doug Dorst. To paraphrase Mr. Abrams' re-boot of the Star Trek series, "S." boldy goes where no fair play mystery has gone before. And make no mistake -- "S." is unapologetically a book in every sense of the word.

To date "S." is available only in hardcover, and if you order it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble you are likely to encounter a “temporarily out of stock” notice. (It took about a week for my volume to arrive from Amazon. "S." is currently listed as out of stock without a delivery estimate at Amazon; Barnes and Noble is projecting shipment no earlier than mid-March). When you do finally get your hands on your own copy of this mystery you will begin to understand why, despite strong interest and positive reviews, sales have out-stripped production by the publisher.

If you order the volume and then wait patiently for delivery, here is what you will eventually hold in your hands -- a handsome cardboard book sleeve containing a hardcover volume, battered and worn, titled Ship of Theseus, purportedly by an author named V.M. Straka. The cardboard box is sealed, and cannot be opened until the paper seal -- the only portion of the book containing the title “S.” -- is broken. Once unsealed, the book presents as a very used library book -- a publication date of 1949, stains on the inside front cover, a “Book for Loan” stamp, a list of check-out stamps on the back inside cover. There is a library index number affixed by sticker on the spine, and the spine itself appears “broken” from frequent opening. When you open the book yourself, it immediately becomes evicent where we, as readers, are headed.

Ship of Theseus is a 453 page novel, complete unto itself. The novel is a good read even standing on its own. But the magic here is that it does not stand on its own. Scribbled throughout all of the pages are notes and annotations by two readers -- Eric, a graduate student who is obsessed with the mysterious Straka, and Jen, a college senior, who has just discovered the author. The premise is that each of them has taken the book from a library shelf, read it, and then returned it to the shelf for the other to re-claim. Eric has initially annotated certain portions in the margin, and Jen responds with her own annotations. Thus begins a dialog that becomes a separate story, sprawling through the pages of Ship of Theseus. In the margins the annotators meet, flirt, and then get down to the task of uncovering the mysteries surrounding Straka and Ship of Theseus, which purportedly was the last of 18 Straka novels (the others are dutifully listed at the front of the book). As if all of this were not enough, as the two annotators discover additional clues or bits of information surrounding the mysterious author, or his equally mysterious translator F. X. Caldeira, they place these snippets of information, or their hand-written summations of what they have uncovered, in the book, at relevant pages, where the reader can extract the clues and follow the evidence at his or her leisure.

And make no mistake -- “leisure” is the right word here. This is a book to be savored, not rushed. In fact, you probably could not rush this book if you wanted to. The reader is called upon to keep track of the underlying Straka novel while, at the same time, following the separate dialog in the margins speculating on the book and the many mysteries surrounding its author. In this respect the book shares some commonality with the underlying theme of Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, discussed at some length in that previous article. The mysterious Stanislas Cordova, who is largely un-seen but occupies the heart of Pessl’s mystery, is eerily similar to the equally-unseen V. M. Straka, who is at the heart of "S.". But back to the point, be prepared to take your time with this book -- you will be rewarded with a near total immersion into the story, a new reading experience that can easily become mesmerizing.

Transforming the concept of the book into a market reality has been a supreme technological challenge, as explained by Abrams in interviews in The New York Times and on CBS. And the problems of the approach continue -- librarians (Rob might like to weigh in here) are perplexed with the challenge of including the book, with all of its loose-leaf clues, on lending shelves, characterizing the task as “a processing nightmare.”

While an ebook version of "S." has been hinted at, it is hard to imagine how this could work. The book, after all, is a throwback -- it is an homage to the published word. In ways it resembles an art book as much as it does a mystery. Could it also be a vanguard? The New York Times had this to say:

Charles Miers, the veteran publisher of the art-book house Rizzoli NY, sees “S.” as part of a larger trend toward such elaborate books, now that digital technology and inexpensive Asian labor have made production newly affordable. “There’s a real interest in the book as an object of permanence, as a direct counterpoint to the digital world, that I haven’t seen before,” he said.The original inspiration for "S." is traceable to the earlier "Mystery Dossiers" of Wheatley and Links, specifically their Who Killed Robert Prentice?, also discussed above and at length in that previous article. In a Los Angeles Times interview Abrams fondly recalled reading that volume: “It had a torn-up photograph in these little wax paper envelopes. As a child, I remember seeing those. That always stayed with me, that idea of getting a book, a packet, that was not just like any other book.” Abrams also acknowledges another catalyst for "S.", a book lending trend that has as well been the subject of some discussion here. According to The New York Times:

Mr. Abrams stumbled upon the idea for “S.” more than a decade ago, when he found a worn Robert Ludlum paperback at Los Angeles International Airport. “Inside, someone had written, ‘To whomever finds this: Please read it, take it, read it and leave it for someone else.’ ” Mr. Abrams said he began thinking about the way his college books had been riddled with marginalia. “What if, instead of putting it back for someone else to read it, the person who received the book saw those notes and felt compelled to continue the conversation?”But perhaps the most remarkable thing about "S." is the way it stubbornly defies modern trends in publishing. This is a book that cannot hope to work well as an e-book. It would never work as a narrated mystery on Audible. It’s hard to imagine that the authors are looking down the road to a paperback edition. What "S." is is an homage to published books -- big, hard cover books, intended to be read and then placed affectionately on a shelf to be retrieved and re-examined in the future. It is about the love affair that can grow between the reader and the volume. There is as much art in the concept as there is in the story -- and this is not meant to denigrate the story, but rather to elevate the concept. Again, according to Abrams:

This is a story about how a book is used as a means of communication and sort of a catalyst for a great investigation that is also a love affair. It is sort of a celebration of ‘the book,’ that physical, analog thing.There may be no room for "S." in that new bookless San Antonio library. That is their loss, but it need not be yours.