People have commented about what kind of entertainment is appropriate - if appropriate is even the word - for this odd time. Do we embrace it, Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year, or Camus, or turn to escapism? Conventional wisdom has it that screwball was so popular during the Depression because it didn't reflect actual living conditions. On the other hand, during the polio epidemic, there was a brief vogue for the iron lung as a story element. Noir mirrors a specific postwar unease, which overlaps Cold War nuclear anxiety. Kiss Me Deadly or Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Godzilla is the atomic metaphor writ large and reptilian.

I seem to be in retreat, myself, falling back on comfort food. Instead of post-apocalyptic, I set sail instead with Dorothy Sayers and her Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries.

Now, right up front, let's admit some of these are pretty lightweight. Whose Body?, the debut, is contrived and gimmicky. Clouds of Witness is stronger, mostly because the stakes are higher. Unnatural Death seems labored, to me, and basically unconvincing - although it introduces the estimable Miss Climpson. I don't think Sayers (and Wimsey) really hit their stride until The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, and I think also this is because Bellona is to some degree about the effects of the Great War on Wimsey and his generation.

Sayers wrote novels of manners; contrivance is less important than character. Wimsey is himself nowhere near the foppish dilettante he affects to present - this is a Scarlet Pimpernel device. (You can easily imagine Leslie Howard in the part, deceptively languid.) Wimsey was a major in the Rifles, and was invalided out. There's a scary moment in Whose Body? when he imagines hearing German sappers digging below, and Bunter has to talk him down and put him to bed. The relationship between Wimsey and Bunter is the spine of the stories.

The other thing we have to acknowledge, which for some readers could be a deal-breaker, is that the language of the period singes the present-day ear. You remember that the books started in the 1920's, so astonishingly, they're almost a hundred years old. This isn't to apologize for Sayers' vocabulary, or rather, the accuracy with which she reports the vocabulary of the British class structure. She doesn't necessarily share their prejudices, but you doubt she's inoculated against them. Then again, Wimsey seems to be playing a part, 'Lord Peter' a kind of self-parody, so how much of this is affectation? It's hard to distinguish between the narrative conventions and Sayers' personal feelings. She herself was apparently quite astonished when somebody suggested anti-Semitic tropes in her work.

The three strongest books are the late-runners, Murder Must Advertise, The Nine Tailors, and Gaudy Night. Murder Must Advertise because it's so effectively mannered - as a novel of manners ought - and because Sayers makes fun of her own successful career as an advertising copywriter. The Nine Tailors because the mystery is so elegant, the bell-ringing so exact, and the surrounding fen country so beautifully evoked. Gaudy Night is an outlier, granted, because it's of course Harriet's book, not Peter's, but the atmospherics are extraordinary, overheated and claustrophobic.

I also recommend The Documents in the Case, which is a standalone, without Wimsey, but the forensics reveal at the end is worth it all by itself.

The other thing about the language in the books, though, is how much it represents a world of the past. Not the late Victorian era of Holmes, but a time we think we can almost reach, from our own experience. Not that many degrees of separation. The period between the wars could be our parents, or theirs. You remember hearing an expression, as a kid, that made no sense whatsoever, because the context belonged to a previous generation. "Clean your plate," my grandmother might say, "think of those starving children in Belgium." Her reference is the First World War.

My personal favorite in the novels is widdershins, which means counter-clockwise, but Wimsey uses it in a particular way, "We do no harm in going widdershins, it's not a church." This puzzled me, until I unearthed a more sinister definition, invoking malign spirits. Originally, however, it seems simply to describe a cowlick or a case of bad hair. And there's the charm.

Showing posts with label Dorothy Sayers. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Dorothy Sayers. Show all posts

08 July 2020

25 March 2020

Sleeping Murder

"Cover her face; mine eyes dazzle."

- The Duchess of Malfi

My pal Carole back in Baltimore recommends the latest BBC adaption of Agatha Christie's The Pale Horse. A cursory search turns up the following, that the book it's based on was influenced to some degree by a contemporary of Christie's named Dennis Wheatley. He was a successful popular novelist at the time, his best-known book being The Devil Rides Out.

Wheatley, whom I've never read, wrote thrillers with a supernatural twist - Satanism, black magic, the paranormal - none of which he apparently put much credit by. He was a sometime acquaintance of Aleister Crowley, and published him at one point, but he doesn't seem to have taken him too seriously. The interesting thing, to me, is the idea of using supernatural themes, whether it's demonic possession or a ghost story, as a counterweight to the rational or the orderly.

This surfaces in Christie, in John Buchan, and in Conan Doyle, to pick major names. Holmes remarks more than once, phrasing it slightly differently, that once you eliminate the impossible, what's left, no matter how improbable, is what happened. The Hound of the Baskervilles generates a lot of its electricity by suggesting the otherworldly - is the dog a physical presence, a phantom, a psychological monster, the manifestation of some past buried evil: a curse, in other words? Kipling fools with it, Robert Louis Stevenson works similar earth, sowing dragon's teeth.

Conan Doyle caught a great deal of ridicule, later in life, for his embrace of spiritualism. Harry Houdini famously disabused him on any number of occasions, but Doyle's enthusiasm wasn't dented. It's an odd irony, we think, that this onetime student of Joseph Bell's (the model for Holmes), the careful exponent of logical argument and defining your terms, trusts a false premise and falls into further delusion. A reversal of the Holmes method, to allow a conclusion to affect your view of the evidence.

Agatha Christie was a master of psychological horror, before it was even recognized as such. Daphne du Maurier comes close, but by the time Rebecca came along, the genre was established. The effect that Christie manages, and almost without fail, is to make you doubt the convention of the narrative. In other words, she gives you the building blocks, using much the same method as Dorothy Sayers or Ngaio Marsh, but you begin to mistrust the design, that in fact the pieces can be assembled in quite the opposite order, or the story turned back to front. Her last published novel, Sleeping Murder, puts all three elements into play, the frisson of the paranormal, the psychological night sweats, and a narrative at right angles to itself.

The story turns on buried memory, and the tension between whether it's actual or imagined. When the weight of memory breaks through the firewall of post-traumatic stress, the "sleeping" murder comes out of hiding. The uncertainty lies in whether you think the heroine is haunted, perhaps literally, traumatized by some childhood nightmare, or just plain nuts. Any one of the three will serve. Christie is entirely at home with these Gothic fugues, and even the confident and resourceful presence of Jane Marple isn't in itself enough to shake your sense of dread. Christie of course contrives a deeply spooky reveal, and you want to go around the house afterwards turning all the lights on.

There's something enormously satisfying about this class of mystery, and the Brits seem to manage it better than anybody else. Christie, like Sayers or du Maurier, and P.D. James, for that matter, is writing novels of manners, often brittle and generally bad - the manners, not the novels. In some sense, they're comfort food, but the best of them leave you uneasy. The era between the wars, seen at a comfortable distance, seems not so far off or foolish. The ghosts are real enough.

- The Duchess of Malfi

My pal Carole back in Baltimore recommends the latest BBC adaption of Agatha Christie's The Pale Horse. A cursory search turns up the following, that the book it's based on was influenced to some degree by a contemporary of Christie's named Dennis Wheatley. He was a successful popular novelist at the time, his best-known book being The Devil Rides Out.

Wheatley, whom I've never read, wrote thrillers with a supernatural twist - Satanism, black magic, the paranormal - none of which he apparently put much credit by. He was a sometime acquaintance of Aleister Crowley, and published him at one point, but he doesn't seem to have taken him too seriously. The interesting thing, to me, is the idea of using supernatural themes, whether it's demonic possession or a ghost story, as a counterweight to the rational or the orderly.

This surfaces in Christie, in John Buchan, and in Conan Doyle, to pick major names. Holmes remarks more than once, phrasing it slightly differently, that once you eliminate the impossible, what's left, no matter how improbable, is what happened. The Hound of the Baskervilles generates a lot of its electricity by suggesting the otherworldly - is the dog a physical presence, a phantom, a psychological monster, the manifestation of some past buried evil: a curse, in other words? Kipling fools with it, Robert Louis Stevenson works similar earth, sowing dragon's teeth.

Conan Doyle caught a great deal of ridicule, later in life, for his embrace of spiritualism. Harry Houdini famously disabused him on any number of occasions, but Doyle's enthusiasm wasn't dented. It's an odd irony, we think, that this onetime student of Joseph Bell's (the model for Holmes), the careful exponent of logical argument and defining your terms, trusts a false premise and falls into further delusion. A reversal of the Holmes method, to allow a conclusion to affect your view of the evidence.

Agatha Christie was a master of psychological horror, before it was even recognized as such. Daphne du Maurier comes close, but by the time Rebecca came along, the genre was established. The effect that Christie manages, and almost without fail, is to make you doubt the convention of the narrative. In other words, she gives you the building blocks, using much the same method as Dorothy Sayers or Ngaio Marsh, but you begin to mistrust the design, that in fact the pieces can be assembled in quite the opposite order, or the story turned back to front. Her last published novel, Sleeping Murder, puts all three elements into play, the frisson of the paranormal, the psychological night sweats, and a narrative at right angles to itself.

The story turns on buried memory, and the tension between whether it's actual or imagined. When the weight of memory breaks through the firewall of post-traumatic stress, the "sleeping" murder comes out of hiding. The uncertainty lies in whether you think the heroine is haunted, perhaps literally, traumatized by some childhood nightmare, or just plain nuts. Any one of the three will serve. Christie is entirely at home with these Gothic fugues, and even the confident and resourceful presence of Jane Marple isn't in itself enough to shake your sense of dread. Christie of course contrives a deeply spooky reveal, and you want to go around the house afterwards turning all the lights on.

There's something enormously satisfying about this class of mystery, and the Brits seem to manage it better than anybody else. Christie, like Sayers or du Maurier, and P.D. James, for that matter, is writing novels of manners, often brittle and generally bad - the manners, not the novels. In some sense, they're comfort food, but the best of them leave you uneasy. The era between the wars, seen at a comfortable distance, seems not so far off or foolish. The ghosts are real enough.

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

Arthur Conan Doyle,

Daphne Du Maurier,

David Edgerley Gates,

Dennis Yates Wheatley,

Dorothy Sayers,

P.D. James,

Sherlock Holmes

13 November 2016

Lost in the Translation

by Leigh Lundin

When it comes to translations, we monolingual North Americans are stuck with (and often stuck waiting for) translations as we catch up to the rest of the literary world. That makes us highly dependent upon the talent of the translator who, if not exactly anonymous, nonetheless wields enormous power over the final result.

The Moving Finger

Upon occasion, translators become almost cult figures. Take for example The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Wikipedia lists about twenty different attempts at translation of the famed Tentmaker’s tantra. (Knowing Wikipedia, we can assume that means between two and twice twenty-two.) Its best known English translator is Edward FitzGerald.

To me, FitzGerald represents an interpreter rather than a translator. He sought more the spirit of the original work than a literal, word-for-word conveyance, but also shaped the product in his own seductive way. Rather than translate the entire body of poetry, FitzGerald chose to transmogrify and rework only five to ten percent of key sections, gradually revising his lexical rendering over time.

The Rubáiyát became highly valued in the latter 1800s and was often printed in gorgeous, gold-illuminated editions. A jewel-encrusted copy was lost on the Titanic. In these days of Middle Eastern xenophobia, it’s worth noting the enormous influence of The Rubáiyát upon our language and culture. It’s difficult to read more than a few dozen quatrains without stumbling upon a familiar phrase such as “a loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou.”

The Rubáiyát is familiar to novelists, especially mystery writers. Many of the golden age authors titled their books or used themes in phrases written by Khayyám. Examples quoting The Rubáiyát include Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple novel The Moving Finger, Stephen King’s similarly named short story The Moving Finger, Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe novel Some Buried Caesar, and Daphne du Maurier titled her memoir Myself when Young. Other genres, especially science fiction, have drawn from the Persian opus.

By Divine Hand

A couple of my college courses studied Dante’s Divine Comedy, specifically Inferno. One professor required students to purchase two translations, Sayers and Ciardi.

Dorothy Sayers is best known to mystery readers for her Lord Peter Wimsey novels and short stories. To scholars, she’s also well regarded for her analysis of La Divina Commedia. Her translation of Dante’s work focused on maintaining the original rhyming structure, which resulted in occasional idiosyncratic wording. However, her notes are considered unparalleled in their detail and accuracy.

John Ciardi, a highly respected poet, began his translation shortly after Sayers. His version became renown for capturing the spirit of The Divine Comedy. Students read Sayers for the technical aspects and Ciardi for the art. Recently, Mark Musa and Robin Kirkpatrick have published ‘more modern’ versions.

Thumbed by Twain

I often enjoy mysteries by non-English authors– French, Russian, Scandinavian, and of course the famed Argentinian, Jorge Luis Borges, who’s been mentioned in these pages. Note that Borges wrote a history of The Rubáiyát and Borges' father, Jorge Guillermo Borges, wrote a Spanish translation of the FitzGerald version of The Rubáiyát.

Sometimes translations turn out less than satisfactory. Mark Twain did a literal retranslation of one of his stories in French back into English with hilarious results. Twain made the point that we can’t always be sure how much of the author’s original sound and feel make their way into other languages. In many cases, it’s difficult to connect with a story as if trying to penetrate an unseen barrier.

The Unseen Hand

Stieg Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander / Mikael Blomkvist series (AKA the Millennium trilogy: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, etc.) impressed me so much, I haven’t yet seen the films– I didn’t want the movies to mess with the image in my mind. I credit the translator for making that bond possible.

Despite my name, I know less Swedish than Latin or even French, possibly even isiZulu. Not a lot of novels are published in Latin these days, so I require not merely an interpreter but a spirit guide.

Reg Keeland seems to be the pseudonym of translator Steven T Murray. According to his bio, Murray works not only in Swedish, but Danish, Norwegian, German, and Spanish. I can’t guess how much of a translator’s influence colors the underlying work, but I suspect less is more, the less visible the better.

I don’t doubt that takes considerable talent. North American fans owe a debt to the unseen hand that made Larsson accessible to English audiences.

Clever fans may notice the title of this article contains a double meaning. A well-done interpretation of a good novel can indeed leave an absorbed reader lost in the translation.

The Moving Finger

Upon occasion, translators become almost cult figures. Take for example The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Wikipedia lists about twenty different attempts at translation of the famed Tentmaker’s tantra. (Knowing Wikipedia, we can assume that means between two and twice twenty-two.) Its best known English translator is Edward FitzGerald.

To me, FitzGerald represents an interpreter rather than a translator. He sought more the spirit of the original work than a literal, word-for-word conveyance, but also shaped the product in his own seductive way. Rather than translate the entire body of poetry, FitzGerald chose to transmogrify and rework only five to ten percent of key sections, gradually revising his lexical rendering over time.

The Rubáiyát became highly valued in the latter 1800s and was often printed in gorgeous, gold-illuminated editions. A jewel-encrusted copy was lost on the Titanic. In these days of Middle Eastern xenophobia, it’s worth noting the enormous influence of The Rubáiyát upon our language and culture. It’s difficult to read more than a few dozen quatrains without stumbling upon a familiar phrase such as “a loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou.”

The Rubáiyát is familiar to novelists, especially mystery writers. Many of the golden age authors titled their books or used themes in phrases written by Khayyám. Examples quoting The Rubáiyát include Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple novel The Moving Finger, Stephen King’s similarly named short story The Moving Finger, Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe novel Some Buried Caesar, and Daphne du Maurier titled her memoir Myself when Young. Other genres, especially science fiction, have drawn from the Persian opus.

| As Rob, Janice, John, Deborah, and I worked to bring this web site to fruition, we struggled to find a perfect name for our cadre. Despite rumors to the contrary, I didn’t come up with ‘SleuthSayers’, Rob Lopresti did and the rest of us burst out with an enthusiastic “Yeah!” Only afterward did it dawn on us the name contained an embedded tip o’ the hat to Dorothy L, kind of a retronym. |

A couple of my college courses studied Dante’s Divine Comedy, specifically Inferno. One professor required students to purchase two translations, Sayers and Ciardi.

Dorothy Sayers is best known to mystery readers for her Lord Peter Wimsey novels and short stories. To scholars, she’s also well regarded for her analysis of La Divina Commedia. Her translation of Dante’s work focused on maintaining the original rhyming structure, which resulted in occasional idiosyncratic wording. However, her notes are considered unparalleled in their detail and accuracy.

John Ciardi, a highly respected poet, began his translation shortly after Sayers. His version became renown for capturing the spirit of The Divine Comedy. Students read Sayers for the technical aspects and Ciardi for the art. Recently, Mark Musa and Robin Kirkpatrick have published ‘more modern’ versions.

Thumbed by Twain

I often enjoy mysteries by non-English authors– French, Russian, Scandinavian, and of course the famed Argentinian, Jorge Luis Borges, who’s been mentioned in these pages. Note that Borges wrote a history of The Rubáiyát and Borges' father, Jorge Guillermo Borges, wrote a Spanish translation of the FitzGerald version of The Rubáiyát.

Sometimes translations turn out less than satisfactory. Mark Twain did a literal retranslation of one of his stories in French back into English with hilarious results. Twain made the point that we can’t always be sure how much of the author’s original sound and feel make their way into other languages. In many cases, it’s difficult to connect with a story as if trying to penetrate an unseen barrier.

The Unseen Hand

Stieg Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander / Mikael Blomkvist series (AKA the Millennium trilogy: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, etc.) impressed me so much, I haven’t yet seen the films– I didn’t want the movies to mess with the image in my mind. I credit the translator for making that bond possible.

Despite my name, I know less Swedish than Latin or even French, possibly even isiZulu. Not a lot of novels are published in Latin these days, so I require not merely an interpreter but a spirit guide.

Reg Keeland seems to be the pseudonym of translator Steven T Murray. According to his bio, Murray works not only in Swedish, but Danish, Norwegian, German, and Spanish. I can’t guess how much of a translator’s influence colors the underlying work, but I suspect less is more, the less visible the better.

I don’t doubt that takes considerable talent. North American fans owe a debt to the unseen hand that made Larsson accessible to English audiences.

Clever fans may notice the title of this article contains a double meaning. A well-done interpretation of a good novel can indeed leave an absorbed reader lost in the translation.

Labels:

Dante,

Dorothy Sayers,

John Ciardi,

Jorge Borges,

Leigh Lundin,

Mark Twain,

Omar Khayyam,

Rubaiyat,

Stieg Larsson

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

09 July 2016

Sayers vs. Aristotle: What's So Funny?

by Unknown

Poor Aristotle. According

to Dorothy L Sayers, he was born at the wrong time, forced to make do

with the likes of Sophocles and Euripides while truly craving, as she

puts it, "a Good Detective Story." In "Aristotle on Detective Fiction," a

1935 Oxford lecture, Sayers takes a look at the philosopher's

definition of tragedy in the Poetics and decides it fits the modern detective story nicely. If Aristotle had been able to get a copy of Trent's Last Case, maybe he would have skipped all those performances of Oedipus Tyrannus and The Trojan Women.

It doesn't do, of course, to challenge Dorothy Sayers on the nature of the detective story. But her lecture seems more than a little tongue in cheek, and her attempt to equate the detective story with tragedy falls short. At its heart, the detective story is more comic than tragic. And I'm willing to bet Sayers knew it.

She begins her lecture by identifying similarities between detective stories and tragedies. Aristotle says action is primary in tragedies, and that's true of detective stories, too. Keeping a straight face, not acknowledging she's made a tiny change in the original, Sayers quotes the Poetics: "The first essential, the life and soul, so to speak, of the detective story, is the Plot." Aristotle says tragic plots must center on "serious" actions. That's another easy matchup, for "murder," as Sayers observes, "is an action of a tolerably serious nature." According to Aristotle, the action of a tragedy must be "complete in itself," it must avoid the improbable and the coincidental, and its "necessary parts" consist of Reversal of Fortune, Discovery, and Suffering. Sayers has no trouble proving good detective stories adhere to all these principles.

When she comes to Aristotle's discussion of Character, however, Sayers has to stretch things a bit. Referring to perhaps the most familiar passage in the Poetics, Sayers cites Aristotle's contention that the central figure in a tragedy should be, as she puts it, "an intermediate kind of person--a decent man with a bad kink in him." Writers of detective stories, Sayers says, agree: "For the more the villain resembles an ordinary man, the more shall we feel pity and horror at his crime and the greater will be our surprise at his detection."

True enough. The problem is that when Aristotle calls for a character brought low not by "vice or depravity" but by "some error or frailty," he's not describing the villain. To use phrases most of us probably learned in high school, he's describing the "tragic hero" who has a "tragic flaw." So the hero of a tragedy is like the villain of a mystery--hardly proof that tragedy and mystery are essentially the same.

This discrepancy points to the central problem with Sayers's argument, a problem of which she was undoubtedly aware. The principal Reversal of Fortune in a tragedy is from prosperity to adversity--but that's just the first half of a detective story. To find a complete model for the plot of the detective story, we must look not to tragedy but to comedy. (Please note, by the way, that Sayers was talking specifically about detective stories, not about mysteries in general. So am I. Thrillers, noir stories, and other varieties of mysteries may not be comic in the least--including some literary mysteries that borrow a few elements of the detective story but really focus on proving life is wretched and pointless, not on solving a crime.)

Unfortunately, Aristotle doesn't provide a full definition of comedy. Scholars say he did write a treatise on comedy, but it was lost over the centuries. The everyday definition of comedy as "something funny" won't cut it. The Divine Comedy isn't a lot of laughs, but who would dare to say Dante mistitled his masterpiece? Turning again to high-school formulas, we can say the essential characteristic of comedy is the happy ending. As the standard shorthand definition has it, tragedies end with funerals, comedies with weddings.

For a more extended definition of comedy, we can look to Northrup Frye's now-classic Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Comedy, Frye says, typically has a three-part structure: It begins with order, dissolves into disorder, and ends with order restored, often at a higher level. Simultaneously, comedy moves "from illusion to reality." Using a comparison that seems especially apt for detective stories, Frye says the action in comedy "is not unlike the action of a lawsuit, in which plaintiff and defendant construct different versions of the same situation, one finally being judged as real and the other as illusory." Along the way, complications arise, but they get resolved through "scenes of discovery and reconciliation." Often, toward the end, comedies include what Frye terms a "point of ritual death," a moment when the protagonist faces terrible danger. But then, "by a twist in the plot," the comic spirit triumphs. Following a "ritual of expulsion which gets rid of some irreconcilable character," things get better for everyone else.

How well does the detective story fit this comic pattern? Pretty darn well. (Frye himself mentions "the amateur detective of modern fiction" as one variation of a classic comic character.) The detective story usually starts with order, or apparent order--the deceptively harmonious English village, the superficially happy family, the workplace where everyone seems to get along. Then a crime--usually murder--plunges everything into disorder. Complications ensue, conflicts escalate, the wrong people get suspected, dangers threaten to engulf the innocent, the guilty evade punishment, and illusion eclipses reality. But the detective starts to set things right during "scenes of discovery and reconciliation." Often after surviving a "point of ritual death" (which he or she may shrug off as a "close call"), the detective identifies the guilty and clears the innocent. The villain is rendered powerless through a "ritual of expulsion"--arrest, violent death, suicide, or, sometimes, escape. Order is restored, and a happy ending is achieved "by a twist in the plot."

To find a specific example, we can turn to Sayers's own detective stories. Gaudy Night makes an especially tempting choice. In the opening chapters, order prevails at quiet Shrewsbury College, and also in the lives of Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane. He proposes at set intervals, and she finds tactful ways to say no. The serenity on campus, however, is more apparent than real. Beneath the surface, tensions and secrets churn.

Then a series of mysterious events shatters the tranquility, and Harriet and Lord Peter get drawn into the chaos. Incidents become increasingly frightening, tensions soar as suspicion shifts from don to don and from student to student, and truth seems hopelessly elusive. Harriet undergoes a "point of ritual death" when she encounters the malefactor in a dark passageway. But "scenes of discovery and reconciliation" follow as Lord Peter unveils the truth, as relationships strained by suspicion heal. Illusions are dispelled, realities recognized. A "ritual of expulsion"--a gentle one this time--removes the person who caused the disorder. And, in the true, full spirit of comedy, the detective story ends with order restored at a higher level, with the promise of a wedding.

How many detective stories end with weddings, or with promises of weddings, as lovers kept apart by danger and suspicion unite in the final chapter? A number of Agatha Christie's works come to mind, along with legions of recent ones that bring together a police officer (usually male) and an amateur sleuth (usually female). Of course, if the author is writing a series and wants to stretch out the sexual tension, the wedding may be delayed--Sayers herself pioneered this technique. Still, the wedding beckons from novel to novel, enticing us with the prospect of an even happier ending after a dozen or so murders have been solved. Romance isn't a necessary element, either in comedies or in detective stories. But it crops up frequently, for it's compatible with the fundamentally optimistic spirit of both.

Humor, too, is compatible with an optimistic spirit, and it's nearly as common in detective stories as in comedies, from Sherlock Holmes's droll asides straight through to Stephanie Plum's one-liners. To some, it may seem tasteless to crack jokes while there's a corpse in the room. On the whole, though, humor seems consistent with the tough-minded attitude of both comedies and detective stories. Neither hides from life's problems--there could be no story without them--but neither responds with weeping or wringing hands. In both genres, protagonists respond to problems by looking for solutions, sustained by their conviction that problems can in fact be solved. The humor reminds both protagonists and readers that, even in the wake of deaths and other disasters, life isn't utterly bleak. Things can still turn out well.

Some might say the comparison with comedy works only if we stick to what is sometimes called the traditional detective story. Yes, Dupin restores order and preserves the reputation of an exalted personage by finding the purloined letter, and Holmes saves an innocent bride-to-be by solving the mystery of the speckled band. But what of darker detective stories? If we stray too far from the English countryside and venture down the mean streets of the hard-boiled P.I. or big-city cop, what traces of comedy will we find? We'll find wisecracks, sure--but they'll be bitter wisecracks, reflecting the world-weary attitudes of the protagonists. In these stories, little order seems to exist in the first place. So how can it be restored? How can an optimistic view of life be affirmed?

The Maltese Falcon looks like a detective story that could hardly be less comic. The mysterious black figurine turns out to be a fake, Sam Spade hands the woman he might love over to the police, and he doesn't even get to keep the lousy thousand bucks he's extracted as his fee. It's not a jolly way to end.

Even so, in some sense, order is restored. Spade has uncovered the truth. He's made sure the innocent remain free and the guilty get punished. He has acted. As he says, "When a man's partner is killed he's supposed to do something about it." Spade has done something.

Maybe, ultimately, that's the defining characteristic of comedy, and of the detective story. Protagonists do something, and endings are happier as a result--maybe not blissfully happy, but more just, more truthful, better. In detective stories, and in comedies, protagonists don't feel so overwhelmed by the unfairness of the universe that they sink into passivity and despair.

Maybe that's the real thesis of "Aristotle on Detective Fiction." In some ways, Sayers's playful comparison of tragedies and detective stories seems unconvincing. Probably, though, her real purpose isn't to argue that the detective story is tragedy rather than comedy. Probably, her purpose is to enlist Aristotle as an ally against what she describes as "that school of thought for which the best kind of play or story is that in which nothing particular happens from beginning to end." That school of thought remains powerful today, praising literary fiction in which helpless, hopeless characters meander morosely through a miserable, meaningless morass, unable to act decisively. Sayers takes a stand for action, for saying the things human beings do make a difference, for saying we are not just victims. Both comedy and the detective story could not agree more.

It doesn't do, of course, to challenge Dorothy Sayers on the nature of the detective story. But her lecture seems more than a little tongue in cheek, and her attempt to equate the detective story with tragedy falls short. At its heart, the detective story is more comic than tragic. And I'm willing to bet Sayers knew it.

She begins her lecture by identifying similarities between detective stories and tragedies. Aristotle says action is primary in tragedies, and that's true of detective stories, too. Keeping a straight face, not acknowledging she's made a tiny change in the original, Sayers quotes the Poetics: "The first essential, the life and soul, so to speak, of the detective story, is the Plot." Aristotle says tragic plots must center on "serious" actions. That's another easy matchup, for "murder," as Sayers observes, "is an action of a tolerably serious nature." According to Aristotle, the action of a tragedy must be "complete in itself," it must avoid the improbable and the coincidental, and its "necessary parts" consist of Reversal of Fortune, Discovery, and Suffering. Sayers has no trouble proving good detective stories adhere to all these principles.

When she comes to Aristotle's discussion of Character, however, Sayers has to stretch things a bit. Referring to perhaps the most familiar passage in the Poetics, Sayers cites Aristotle's contention that the central figure in a tragedy should be, as she puts it, "an intermediate kind of person--a decent man with a bad kink in him." Writers of detective stories, Sayers says, agree: "For the more the villain resembles an ordinary man, the more shall we feel pity and horror at his crime and the greater will be our surprise at his detection."

True enough. The problem is that when Aristotle calls for a character brought low not by "vice or depravity" but by "some error or frailty," he's not describing the villain. To use phrases most of us probably learned in high school, he's describing the "tragic hero" who has a "tragic flaw." So the hero of a tragedy is like the villain of a mystery--hardly proof that tragedy and mystery are essentially the same.

This discrepancy points to the central problem with Sayers's argument, a problem of which she was undoubtedly aware. The principal Reversal of Fortune in a tragedy is from prosperity to adversity--but that's just the first half of a detective story. To find a complete model for the plot of the detective story, we must look not to tragedy but to comedy. (Please note, by the way, that Sayers was talking specifically about detective stories, not about mysteries in general. So am I. Thrillers, noir stories, and other varieties of mysteries may not be comic in the least--including some literary mysteries that borrow a few elements of the detective story but really focus on proving life is wretched and pointless, not on solving a crime.)

Unfortunately, Aristotle doesn't provide a full definition of comedy. Scholars say he did write a treatise on comedy, but it was lost over the centuries. The everyday definition of comedy as "something funny" won't cut it. The Divine Comedy isn't a lot of laughs, but who would dare to say Dante mistitled his masterpiece? Turning again to high-school formulas, we can say the essential characteristic of comedy is the happy ending. As the standard shorthand definition has it, tragedies end with funerals, comedies with weddings.

For a more extended definition of comedy, we can look to Northrup Frye's now-classic Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Comedy, Frye says, typically has a three-part structure: It begins with order, dissolves into disorder, and ends with order restored, often at a higher level. Simultaneously, comedy moves "from illusion to reality." Using a comparison that seems especially apt for detective stories, Frye says the action in comedy "is not unlike the action of a lawsuit, in which plaintiff and defendant construct different versions of the same situation, one finally being judged as real and the other as illusory." Along the way, complications arise, but they get resolved through "scenes of discovery and reconciliation." Often, toward the end, comedies include what Frye terms a "point of ritual death," a moment when the protagonist faces terrible danger. But then, "by a twist in the plot," the comic spirit triumphs. Following a "ritual of expulsion which gets rid of some irreconcilable character," things get better for everyone else.

How well does the detective story fit this comic pattern? Pretty darn well. (Frye himself mentions "the amateur detective of modern fiction" as one variation of a classic comic character.) The detective story usually starts with order, or apparent order--the deceptively harmonious English village, the superficially happy family, the workplace where everyone seems to get along. Then a crime--usually murder--plunges everything into disorder. Complications ensue, conflicts escalate, the wrong people get suspected, dangers threaten to engulf the innocent, the guilty evade punishment, and illusion eclipses reality. But the detective starts to set things right during "scenes of discovery and reconciliation." Often after surviving a "point of ritual death" (which he or she may shrug off as a "close call"), the detective identifies the guilty and clears the innocent. The villain is rendered powerless through a "ritual of expulsion"--arrest, violent death, suicide, or, sometimes, escape. Order is restored, and a happy ending is achieved "by a twist in the plot."

To find a specific example, we can turn to Sayers's own detective stories. Gaudy Night makes an especially tempting choice. In the opening chapters, order prevails at quiet Shrewsbury College, and also in the lives of Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane. He proposes at set intervals, and she finds tactful ways to say no. The serenity on campus, however, is more apparent than real. Beneath the surface, tensions and secrets churn.

Then a series of mysterious events shatters the tranquility, and Harriet and Lord Peter get drawn into the chaos. Incidents become increasingly frightening, tensions soar as suspicion shifts from don to don and from student to student, and truth seems hopelessly elusive. Harriet undergoes a "point of ritual death" when she encounters the malefactor in a dark passageway. But "scenes of discovery and reconciliation" follow as Lord Peter unveils the truth, as relationships strained by suspicion heal. Illusions are dispelled, realities recognized. A "ritual of expulsion"--a gentle one this time--removes the person who caused the disorder. And, in the true, full spirit of comedy, the detective story ends with order restored at a higher level, with the promise of a wedding.

How many detective stories end with weddings, or with promises of weddings, as lovers kept apart by danger and suspicion unite in the final chapter? A number of Agatha Christie's works come to mind, along with legions of recent ones that bring together a police officer (usually male) and an amateur sleuth (usually female). Of course, if the author is writing a series and wants to stretch out the sexual tension, the wedding may be delayed--Sayers herself pioneered this technique. Still, the wedding beckons from novel to novel, enticing us with the prospect of an even happier ending after a dozen or so murders have been solved. Romance isn't a necessary element, either in comedies or in detective stories. But it crops up frequently, for it's compatible with the fundamentally optimistic spirit of both.

Humor, too, is compatible with an optimistic spirit, and it's nearly as common in detective stories as in comedies, from Sherlock Holmes's droll asides straight through to Stephanie Plum's one-liners. To some, it may seem tasteless to crack jokes while there's a corpse in the room. On the whole, though, humor seems consistent with the tough-minded attitude of both comedies and detective stories. Neither hides from life's problems--there could be no story without them--but neither responds with weeping or wringing hands. In both genres, protagonists respond to problems by looking for solutions, sustained by their conviction that problems can in fact be solved. The humor reminds both protagonists and readers that, even in the wake of deaths and other disasters, life isn't utterly bleak. Things can still turn out well.

Some might say the comparison with comedy works only if we stick to what is sometimes called the traditional detective story. Yes, Dupin restores order and preserves the reputation of an exalted personage by finding the purloined letter, and Holmes saves an innocent bride-to-be by solving the mystery of the speckled band. But what of darker detective stories? If we stray too far from the English countryside and venture down the mean streets of the hard-boiled P.I. or big-city cop, what traces of comedy will we find? We'll find wisecracks, sure--but they'll be bitter wisecracks, reflecting the world-weary attitudes of the protagonists. In these stories, little order seems to exist in the first place. So how can it be restored? How can an optimistic view of life be affirmed?

The Maltese Falcon looks like a detective story that could hardly be less comic. The mysterious black figurine turns out to be a fake, Sam Spade hands the woman he might love over to the police, and he doesn't even get to keep the lousy thousand bucks he's extracted as his fee. It's not a jolly way to end.

Even so, in some sense, order is restored. Spade has uncovered the truth. He's made sure the innocent remain free and the guilty get punished. He has acted. As he says, "When a man's partner is killed he's supposed to do something about it." Spade has done something.

Maybe, ultimately, that's the defining characteristic of comedy, and of the detective story. Protagonists do something, and endings are happier as a result--maybe not blissfully happy, but more just, more truthful, better. In detective stories, and in comedies, protagonists don't feel so overwhelmed by the unfairness of the universe that they sink into passivity and despair.

Maybe that's the real thesis of "Aristotle on Detective Fiction." In some ways, Sayers's playful comparison of tragedies and detective stories seems unconvincing. Probably, though, her real purpose isn't to argue that the detective story is tragedy rather than comedy. Probably, her purpose is to enlist Aristotle as an ally against what she describes as "that school of thought for which the best kind of play or story is that in which nothing particular happens from beginning to end." That school of thought remains powerful today, praising literary fiction in which helpless, hopeless characters meander morosely through a miserable, meaningless morass, unable to act decisively. Sayers takes a stand for action, for saying the things human beings do make a difference, for saying we are not just victims. Both comedy and the detective story could not agree more.

Labels:

B.K. Stevens,

comedy,

detectives,

Dorothy Sayers,

humor,

humour,

Maltese Falcon,

stories

09 January 2016

Of Lords and Eggs

by Unknown

Mystery short stories offer

us many pleasures, including the opportunity to enjoy,

briefly, the company of protagonists who might drive us crazy if we

tried to stick with them through an entire novel. I was reminded of this

truth recently when I reread a Dorothy L. Sayers story featuring

Montague Egg, a traveling salesman who deals in wines and spirits. Most

Sayers mysteries, of course, center on another protagonist, Lord Peter

Wimsey. As almost all mystery readers know, Lord Peter is highly

intelligent, unusually observant, and adept at figuring out how

scattered scraps of information come together to point to a conclusion.

Montague Egg fits that description, too. Both characters are engaging

and articulate, both have exemplary manners, and both sprinkle their

statements with lively quotations. More important, both Lord Peter and

Montague Egg abide by codes of honor, and both are devoted to the cause

of justice, to identifying the guilty and exonerating the innocent. And

Sayers evidently found both protagonists charming: She kept returning to

them for years, writing twenty-one short stories about Lord Peter,

eleven about Montague Egg.

But while Sayers also wrote eleven novels about Lord Peter,

she didn't write a single one about Montague Egg. I don't know if she

ever explained why she wrote only short stories about him--I checked two

biographies and didn't find anything, but there might be an explanation

somewhere. In any case, it's tempting to speculate about what her

reasons might have been.She

might have thought Egg lacks the depth of character needed in the

protagonist of a novel. That's true enough, but she could always have

developed his character further, given him more backstory. She did that

with Lord Peter, who's a far more complex, tormented soul in Gaudy Night and Busman's Honeymoon than he is in Whose Body?

Or perhaps she thought all the little quirks that make Montague Egg

such an amusing, distinctive short story protagonist would make him hard

to take if his adventures were stretched out into a novel. Yes, Lord

Peter has his little quirks, too, but I think his are qualitatively

different. For example, while Lord peter tends to quote works of English

literature in delightfully surprising contexts, Montague Egg sticks to

quoting maxims from the fictional Salesman's Handbook, such as

"Whether you're wrong or whether you're right, it's always better to be

polite." Three or four of these common-sense rhymes add humor to a quick

short story. Dozens of them might leave readers wincing long before a

novel ends.

I did plenty of wincing when I decided, not long ago, to read Anita Loos' Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

(not a mystery, but protagonist Lorelei Lee does go on trial for

shooting Mr. Jennings, so I figure I can sneak it in as an example). For

the first thirty pages or so, I relished it, laughing out loud at

Lorelei's uninhibited voice, at the absurd situations, at the appalling

but flat-out funny inversions of anything resembling real values. Before

long, however, I was flipping to the back of this short book to see how

many more pages I had to read before I could declare myself done.

Lorelei's voice, which had been so entertaining at first, had started to

get on my nerves, and her delusions and her shallowness were becoming

hard to take. I couldn't understand why this book had been so wildly

popular until I found out it had originally been a series of short

stories in Harper's Bazaar. Well, sure. A small dose of Lorelei

once in a while can be enjoyable, but spending hours with her is like

getting stuck talking to the most self-centered, superficial guest at a

party. If you ever decide to read Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, I recommend reading it one chapter at a time, and taking at least a week off in between.

There could be all sorts of reasons that a protagonist might be right for short stories but wrong for novels. I wrote a series of stories (for Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine) about dim-witted Lieutenant Walt Johnson and overly modest Sergeant Gordon Bolt. Everyone--including Bolt--sees Walt as a genius who cracks case after difficult case. In fact, Walt consistently misunderstands all the evidence, and it's Bolt who solves the cases by reading deep meanings into Walt's clueless remarks. A number of readers urged me to write a novel about this detective team. (And yes, you're right--most of these readers are members of my immediate family. They still count as readers.)

Despite my fondness for Walt and Bolt, though, I never even considered writing a novel about them. I think they're two of the most likable, amusing characters I've ever created. But Walt is too dense, too anxious, and too cowardly to sustain a novel. How long can readers be expected to put up with a detective who's always confused but never scrapes up the courage to admit it, no matter how guilty he feels about taking credit for Bolt's deductions? And while I find Bolt's self-effacing admiration for Walt sweet and endearing, I think readers would get fed up with his blindness before reaching the end of Chapter Two.

I think these two are amusing short-story characters precisely because they're locked into patterns of foolish behavior. As Henri Bergson says in Laughter, repetition is often a fundamental element in comedy. But this sort of comedy would, I think, get frustrating in a novel. Readers expect the protagonists in novels to learn, to change, to grow. Walt and Bolt can't learn, change, or grow without betraying the premise for the series. So I confined them to twelve short stories, spread out between 1988 and 2014. In the story that completed the dozen, I brought the series to an end, doing my best to orchestrate a finale that would leave both characters and readers happy--a promotion to an administrative job for Walt, so he can stop pretending he's capable of detecting anything, and a long-awaited wedding and an adventure-filled retirement for Bolt. I truly love these characters. But I'd never trust them with a novel.

Other short-story protagonists, though, do have what it takes to be protagonists in novels, too. Lord Peter Wimsey is one example--in fact, most readers would probably agree that, delightful as most of the stories about him are, the novels are even better. Sherlock Holmes is another example--four novels, fifty-six short stories, and I think it's fair to say he shines in both genres. I considered one of my own short-story protagonists so promising that I decided to build a novel around her. Before I could do that, though, I had to make some major changes in her character.

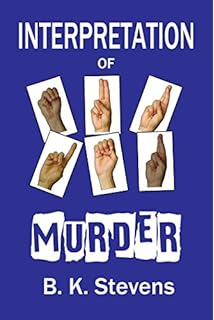

American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi first appeared in a December, 2010 Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine story, now republished as a Kindle story called "Silent Witness." Positive responses to the story--including a Derringer from the Short Mystery Fiction Society--encouraged me to think I might be able to do more with the character. It also helped that one of my daughters is an ASL interpreter who can scrutinize drafts and provide insights into deaf culture and the ethical dilemmas interpreters face. And I like Jane. She's smart, she's observant, she has acute insights into human nature, and she has a strong sense of right and wrong. In "Silent Witness," when she interprets at the trial of a deaf man accused of murdering his employer, she wants the truth to come out. She definitely doesn't want to see an innocent man go to prison.

But

the Jane Ciardi of "Silent Witness" is mostly passive. She's sharp

enough to figure out the truth and to realize what she should do, but

she lacks the courage to follow through. Her final action in the story

is to fail to act, to sit when she should stand, to convince herself

justice will probably be done even if she remains silent. I think all

that makes Jane an interesting, believable protagonist in a short story

that raises questions it doesn't quite answer.

But

the Jane Ciardi of "Silent Witness" is mostly passive. She's sharp

enough to figure out the truth and to realize what she should do, but

she lacks the courage to follow through. Her final action in the story

is to fail to act, to sit when she should stand, to convince herself

justice will probably be done even if she remains silent. I think all

that makes Jane an interesting, believable protagonist in a short story

that raises questions it doesn't quite answer.

I don't think it's enough to make her a fully satisfying protagonist in a novel--at least, not in a traditional mystery novel. In what's often called a literary novel, the Jane of "Silent Witness" might do fine--another protagonist paralyzed by doubt, agonizing endlessly about right and wrong but never taking decisive action. The protagonists of traditional mysteries should be made of sterner stuff. So in Interpretation of Murder, I made Jane regret and learn from the mistakes she'd made in "Silent Witness." We find out she did her best to correct them, even though it hurt her professionally. And when she's drawn into another murder case, she works actively to uncover the truth, she comes up with inventive ways of gathering evidence, and she speaks out about what she's discovered even when situations get dangerous. I can't be objective about Jane--others will have to decide if these changes were enough to make her an effective protagonist for Interpretation of Murder. But I'm pretty sure mystery readers would find the Jane of "Silent Witness" a disappointing companion if they had to read an entire novel about her.

Have you encountered mystery characters who are effective protagonists in short stories but not in novels--or, perhaps, in novels but not in short stories? If you're a writer, have you decided some of your protagonists work well in one genre but not in the other? If you've used the same protagonist in both stories and novels, have you had to make adjustments? I'd love to hear your comments.

There could be all sorts of reasons that a protagonist might be right for short stories but wrong for novels. I wrote a series of stories (for Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine) about dim-witted Lieutenant Walt Johnson and overly modest Sergeant Gordon Bolt. Everyone--including Bolt--sees Walt as a genius who cracks case after difficult case. In fact, Walt consistently misunderstands all the evidence, and it's Bolt who solves the cases by reading deep meanings into Walt's clueless remarks. A number of readers urged me to write a novel about this detective team. (And yes, you're right--most of these readers are members of my immediate family. They still count as readers.)

Despite my fondness for Walt and Bolt, though, I never even considered writing a novel about them. I think they're two of the most likable, amusing characters I've ever created. But Walt is too dense, too anxious, and too cowardly to sustain a novel. How long can readers be expected to put up with a detective who's always confused but never scrapes up the courage to admit it, no matter how guilty he feels about taking credit for Bolt's deductions? And while I find Bolt's self-effacing admiration for Walt sweet and endearing, I think readers would get fed up with his blindness before reaching the end of Chapter Two.

I think these two are amusing short-story characters precisely because they're locked into patterns of foolish behavior. As Henri Bergson says in Laughter, repetition is often a fundamental element in comedy. But this sort of comedy would, I think, get frustrating in a novel. Readers expect the protagonists in novels to learn, to change, to grow. Walt and Bolt can't learn, change, or grow without betraying the premise for the series. So I confined them to twelve short stories, spread out between 1988 and 2014. In the story that completed the dozen, I brought the series to an end, doing my best to orchestrate a finale that would leave both characters and readers happy--a promotion to an administrative job for Walt, so he can stop pretending he's capable of detecting anything, and a long-awaited wedding and an adventure-filled retirement for Bolt. I truly love these characters. But I'd never trust them with a novel.

Other short-story protagonists, though, do have what it takes to be protagonists in novels, too. Lord Peter Wimsey is one example--in fact, most readers would probably agree that, delightful as most of the stories about him are, the novels are even better. Sherlock Holmes is another example--four novels, fifty-six short stories, and I think it's fair to say he shines in both genres. I considered one of my own short-story protagonists so promising that I decided to build a novel around her. Before I could do that, though, I had to make some major changes in her character.

American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi first appeared in a December, 2010 Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine story, now republished as a Kindle story called "Silent Witness." Positive responses to the story--including a Derringer from the Short Mystery Fiction Society--encouraged me to think I might be able to do more with the character. It also helped that one of my daughters is an ASL interpreter who can scrutinize drafts and provide insights into deaf culture and the ethical dilemmas interpreters face. And I like Jane. She's smart, she's observant, she has acute insights into human nature, and she has a strong sense of right and wrong. In "Silent Witness," when she interprets at the trial of a deaf man accused of murdering his employer, she wants the truth to come out. She definitely doesn't want to see an innocent man go to prison.

I don't think it's enough to make her a fully satisfying protagonist in a novel--at least, not in a traditional mystery novel. In what's often called a literary novel, the Jane of "Silent Witness" might do fine--another protagonist paralyzed by doubt, agonizing endlessly about right and wrong but never taking decisive action. The protagonists of traditional mysteries should be made of sterner stuff. So in Interpretation of Murder, I made Jane regret and learn from the mistakes she'd made in "Silent Witness." We find out she did her best to correct them, even though it hurt her professionally. And when she's drawn into another murder case, she works actively to uncover the truth, she comes up with inventive ways of gathering evidence, and she speaks out about what she's discovered even when situations get dangerous. I can't be objective about Jane--others will have to decide if these changes were enough to make her an effective protagonist for Interpretation of Murder. But I'm pretty sure mystery readers would find the Jane of "Silent Witness" a disappointing companion if they had to read an entire novel about her.

Have you encountered mystery characters who are effective protagonists in short stories but not in novels--or, perhaps, in novels but not in short stories? If you're a writer, have you decided some of your protagonists work well in one genre but not in the other? If you've used the same protagonist in both stories and novels, have you had to make adjustments? I'd love to hear your comments.

03 September 2015

Serial Offenders

by Janice Law

Like most mystery fans, I have my favorites, characters I willingly read about time and again. Indeed, what lover of the genre wouldn’t like just one more Sherlock Holmes story or another vintage appearance from Lord Peter Whimsy or Adam Dalgliesh? Familiarity breeds contentment for the reader. The writer is another breed of cat.

Writers enjoy variety, new challenges, new plots, new directions, and perhaps for that reason even wildly successful mystery writers have sometimes had complicated feelings about their heroes and heroines. Demands for another helping of the same can arouse a homicidal streak – of the literary sort. Thus Conan Doyle sent Holmes over the Reichenback Falls and Henning Mankell gave Wallander not one, but two deadly illnesses. Agatha Christie wrote – then stored– Curtain, Poirot’s exit, at the height of her powers, while Dorothy Sayers, faced with either killing off or marrying off Lord Peter, mercifully opted for the latter. He was never the same in any case.

During my career, now longer than I like to mention, I’ve twice created serial characters, each begun as a one off. Anna Peters was never projected to live beyond The Big Payoff and my second novel used other characters entirely. Alas, Houghton Mifflin, my publisher at the time, was not enthralled, and the new novel was destined to be unlucky. Bought by Macmillan – or so I thought – the deal fell through when the entire mystery division was folded.

Back to Miss Peters, as she was then. Nine more books followed. They got good reviews and foreign translations and sold modestly well, although not ultimately well enough for the modern publishing conglomerate. I did learn one thing I’ll pass on to those contemplating a mystery series: don’t age your character.

Sure, aging a character keeps the writer from getting bored, but in five years, not to mention ten or twenty years down the road, you’re getting long in the tooth and so is your detective. Poor Anna got back trouble and was getting too old for derring do. I was faced with killing her, retiring her, or turning her into Miss Marple.

I chose to have her sell Executive Security, Inc. and retire ( some of her adventures are still available from Wildside Press). I imagined her sitting in on interesting college courses and wondered about a campus mystery. But I was teaching college courses myself at the time, and a campus setting sounded too much like my day job.

For at least a decade (actually, I suspect two) I stayed away from series characters. I published some contemporary novels with strong mystery elements and lots of short stories. I liked those because I didn’t need to love the assorted obsessives and malcontents that populated them. I just needed to like them enough for 10-14 pages worth.

Then came Madame Selina, a nineteenth century New York City medium, whose adventures were narrated by her assistant, a boy straight out of the Orphan Home named Nip Tompkins. Once again, I figured a one off, but a suggestion from fellow Sleuthsayer Rob Lopresti that she’d make a good series character led me write one more – pretty much just to see if he was wrong.

That proved lucky, as she has inspired in nine or ten stories, all of which have appeared or will appear in Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Thank you, Rob. However, there is a season for all things, and having explored many of the key issues of the nineteenth century with Madame Selina and Nip, I am beginning to tire of mysteries that can be wrapped up with a seance. That, by the way, gets harder each time out.

What to do? I’m not so ruthless as to kill off a woman who’s worked hard for me. But as she’s observed herself, times are changing and the Civil War, so horrible but so conducive to her profession, is now a decade past. As you see, I learned nothing from my experience with Anna Peters, as both Madame and Nip have continued to age.

I don’t think I’ll marry her off, either, although she knows a rich financier who might fill the bill. Instead, I think I’ll let her sell her townhouse and retire, perhaps to one of the resorts she favors, Saratoga or, better because I know the area, Newport, where she will take up gardening and grow prize roses or dahlias.

As for Nip, I’ve already picked his profession. Snooping for Madame Selina has given him every skill he needs to be a newspaperman in the great age of Yellow Journalism. Will the now teenaged Nip show up in print again?

We’ll see.

Writers enjoy variety, new challenges, new plots, new directions, and perhaps for that reason even wildly successful mystery writers have sometimes had complicated feelings about their heroes and heroines. Demands for another helping of the same can arouse a homicidal streak – of the literary sort. Thus Conan Doyle sent Holmes over the Reichenback Falls and Henning Mankell gave Wallander not one, but two deadly illnesses. Agatha Christie wrote – then stored– Curtain, Poirot’s exit, at the height of her powers, while Dorothy Sayers, faced with either killing off or marrying off Lord Peter, mercifully opted for the latter. He was never the same in any case.

|

| first POD for Anna. My design |

Back to Miss Peters, as she was then. Nine more books followed. They got good reviews and foreign translations and sold modestly well, although not ultimately well enough for the modern publishing conglomerate. I did learn one thing I’ll pass on to those contemplating a mystery series: don’t age your character.

Sure, aging a character keeps the writer from getting bored, but in five years, not to mention ten or twenty years down the road, you’re getting long in the tooth and so is your detective. Poor Anna got back trouble and was getting too old for derring do. I was faced with killing her, retiring her, or turning her into Miss Marple.

I chose to have her sell Executive Security, Inc. and retire ( some of her adventures are still available from Wildside Press). I imagined her sitting in on interesting college courses and wondered about a campus mystery. But I was teaching college courses myself at the time, and a campus setting sounded too much like my day job.

|

| Wildside edition, last Anna Peters |

Then came Madame Selina, a nineteenth century New York City medium, whose adventures were narrated by her assistant, a boy straight out of the Orphan Home named Nip Tompkins. Once again, I figured a one off, but a suggestion from fellow Sleuthsayer Rob Lopresti that she’d make a good series character led me write one more – pretty much just to see if he was wrong.

That proved lucky, as she has inspired in nine or ten stories, all of which have appeared or will appear in Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Thank you, Rob. However, there is a season for all things, and having explored many of the key issues of the nineteenth century with Madame Selina and Nip, I am beginning to tire of mysteries that can be wrapped up with a seance. That, by the way, gets harder each time out.

What to do? I’m not so ruthless as to kill off a woman who’s worked hard for me. But as she’s observed herself, times are changing and the Civil War, so horrible but so conducive to her profession, is now a decade past. As you see, I learned nothing from my experience with Anna Peters, as both Madame and Nip have continued to age.

I don’t think I’ll marry her off, either, although she knows a rich financier who might fill the bill. Instead, I think I’ll let her sell her townhouse and retire, perhaps to one of the resorts she favors, Saratoga or, better because I know the area, Newport, where she will take up gardening and grow prize roses or dahlias.

As for Nip, I’ve already picked his profession. Snooping for Madame Selina has given him every skill he needs to be a newspaperman in the great age of Yellow Journalism. Will the now teenaged Nip show up in print again?

We’ll see.

07 May 2015

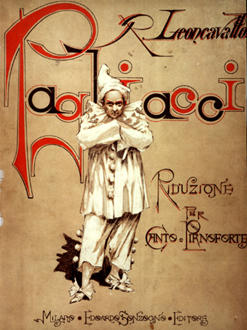

Pagliacci, or, Killing Your Lover is as Old as the Hills

by Eve Fisher

I went to the opera last weekend - The Met Live in HD at the Sioux Falls Century 14, big screen, great sound, and subtitles, what more could you ask for? They were showing Pagliacci. Now I'd heard about that opera all my life - everything from people on the old Ed Sullivan show singing their guts out to an Elmer Fudd parody. But I'd never seen it, so off I went, and enjoyed it a lot. Good old drama: jealousy, threats, attempted rape, betrayal, adultery and murder. What's not to like? Plus a play-within-a-play (which I am always a sucker for).

I went to the opera last weekend - The Met Live in HD at the Sioux Falls Century 14, big screen, great sound, and subtitles, what more could you ask for? They were showing Pagliacci. Now I'd heard about that opera all my life - everything from people on the old Ed Sullivan show singing their guts out to an Elmer Fudd parody. But I'd never seen it, so off I went, and enjoyed it a lot. Good old drama: jealousy, threats, attempted rape, betrayal, adultery and murder. What's not to like? Plus a play-within-a-play (which I am always a sucker for). The plot is simple: Act One: Traveling players, commedia dell'arte, arrive in a small Sicilian town, and set up shop. Canio (who plays the clown Pagliacci) is married to the beautiful Nedda (who plays the romantic heroine Columbine). The foreshadowing was the joshing about how (on stage) Columbine cuckolds Pagliacci every night with Arlecchino (Harlequin), and Canio said, hey what's on stage is fine, but in real life, I'd kill her. Cue the dramatic music, and they did. On comes the big thug Tonio (who plays Taddeo, a servant in the play-within-a-play), who wants Nedda and tries to rape her. She drives him off with a whip and he vows revenge. So he overhears and then oversees Nedda meeting up with her real lover, Silvio. He goes off, tells Canio, who gets drunk and weeps his aria, "I Pagliacci" while he puts on his white clown make-up.

Act Two: The Harlequinade, as Columbine gets ready for her tryst with Arlecchino. Taddeo wants her, she drives him off. Pagliacci arrives - but Canio/Pagliacci is murderously drunk and playing for real. (The audience, bloodthirsty as they come, is enthralled by his realism.) He chases her around the stage, they fight, and he stabs her to death. With her dying breath she calls "Silvio!" and, as Silvio fights his way up onto the stage, Canio/Pagliacci grabs him and stabs him to death, too. And then turns to the audience and cries, "La commedia è finita!" – "The comedy is finished!" Short, sweet, violent.

Pagiliacci, Cavallere Rusticana, and other operas were all part of the versimo movement of the late 1800's. Naturalism! Realism! Lots of violence! Lots of sex! Bodies piled up on the stage! (like that hadn't been done before - hadn't they ever noticed the Shakespearean body count?) And, of course, everyone is no good. Very much like film noir. The literature of the day was the same: whenever you want a good, depressing time among adulterers, thieves, murderers, whores and corrupt politicians, try Emile Zola's brilliant, harrowing, brutal Therese Raquin, Nana, and La Cousine Bette.

Pagiliacci, Cavallere Rusticana, and other operas were all part of the versimo movement of the late 1800's. Naturalism! Realism! Lots of violence! Lots of sex! Bodies piled up on the stage! (like that hadn't been done before - hadn't they ever noticed the Shakespearean body count?) And, of course, everyone is no good. Very much like film noir. The literature of the day was the same: whenever you want a good, depressing time among adulterers, thieves, murderers, whores and corrupt politicians, try Emile Zola's brilliant, harrowing, brutal Therese Raquin, Nana, and La Cousine Bette. But if that wasn't enough excitement for you - not enough sex, not enough violence, not enough B&D, S&M - you went to the Grand Guignol, where the old tradition of violence on stage was revived. Blood Feast, eat your heart out. Even Titus Andronicus didn't quite reach the levels of violence porn that the Grand Guignol did in its theater on the Rue Pigalle. From 1897 to 1962, they presented such upscale entertainment as Andre de Lorde's:

|

| Grand Guignol, 1932 |

- Le Laboratoire des Hallucinations: When a doctor finds his wife's lover in his operating room, he performs a graphic brain surgery rendering the adulterer a hallucinating semi-zombie. Now insane, the lover/patient hammers a chisel into the doctor's brain.

- Un Crime dans une Maison de Fous: Two hags in an insane asylum use scissors to blind a young, pretty fellow inmate out of jealousy.

- L'Horrible Passion: A nanny strangles the children in her care. (Synopses thanks to Wikipedia.)

(On the other hand, even the Grand Guignol didn't reach the heights of ancient Rome, where wealthy diners could and were treated to the entertainment of live gladiator contests, and theatergoers would be treated, in "The Death of Hercules", to an ending that included condemned criminal being burned to death in front of them. Humans do love violence porn...)

And they also love magic, dance, and romance. Which is also at the heart of Pagliacci. The Harlequinade that Canio and Nedda perform in Act 2 is straight from the commedia dell'arte, a staple and source of European entertainment for centuries, which always involved romance and sometimes murder. Characters from the commedia show up in Mozart operas, Shakespearean plays, and innumerable other operas and ballets. And mysteries: Sir Peter Wimsey dressed as Harlequin for half the plot of Murder Must Advertise, and Agatha Christie used the commedia over and over again as a trope or theme or a plot point, and at one point even a character - Harley Quin, who appeared in at least a dozen short stories.

And they also love magic, dance, and romance. Which is also at the heart of Pagliacci. The Harlequinade that Canio and Nedda perform in Act 2 is straight from the commedia dell'arte, a staple and source of European entertainment for centuries, which always involved romance and sometimes murder. Characters from the commedia show up in Mozart operas, Shakespearean plays, and innumerable other operas and ballets. And mysteries: Sir Peter Wimsey dressed as Harlequin for half the plot of Murder Must Advertise, and Agatha Christie used the commedia over and over again as a trope or theme or a plot point, and at one point even a character - Harley Quin, who appeared in at least a dozen short stories.The original commedia dell'arte was all about lovers (innamorate) who wanted to marry, but were hindered by elders (vecchio) and helped by servants (zanni). In the old companies (old being 1500-1700s) there would be 10 characters: two vecchi (old men), four innamorati (two male/female couples, one noble or at least middle class, the other lower class or downright clowns), two zanni, a Captain and a servetta (serving maid). That gave plenty of characters to interfere with the two classes of lovers.

|

| Papageno and Papagena |

BTW, this structure of thwarted/thwarting/attempting to thwart lovers, operating on two levels, is an old plot device. In "As You Like It", Rosalind and Orlando, the noble lovers, are balanced off by Touchstone and Audrey, the comic relief. In "The Magic Flute", the noble lovers Tamino and Pamina are balanced by Papageno and Papagena. In Anthony Trollope's "Can You Forgive Her?" there's a series of triangles: in the noble group, Plantagenet Palliser and Burgo Fitzgerald vie for Lady Glencora (PP's wife), in the middle-class group, George Vavasor and John Gray vie for Alice Vavasor, and in the lower-class group, Captain Bellfield and Squire Cheesacre vie for the Widow Greenow, and the latter three (the most hilarious) are straight out of the classic comic commedia dell'arte: smart woman, miser, and the captain.Anyway, the characters and plot lines went all the way back to ancient Greek and Roman plays, and were continually updated and remade. The major characters were:

Harlequin (a/k/a Arlecchino) - in love with and the beloved of Columbine. Originally, Harlequin - and this is what makes him very interesting - was an emissary of the Devil, and was played with a red and black mask and the motley costume that the demon(s) used to wear in the old Medieval Mystery Plays. An athletic, acrobatic trickster, he was transformed over time into a more romantic figure. But he remained a magician, and he could either be hilariously clever or diabolically deadly... Even to Columbine...

Harlequin (a/k/a Arlecchino) - in love with and the beloved of Columbine. Originally, Harlequin - and this is what makes him very interesting - was an emissary of the Devil, and was played with a red and black mask and the motley costume that the demon(s) used to wear in the old Medieval Mystery Plays. An athletic, acrobatic trickster, he was transformed over time into a more romantic figure. But he remained a magician, and he could either be hilariously clever or diabolically deadly... Even to Columbine...Columbine - beautiful, witty, often the wife of Pierrot (Pagliacci), but always in love with Harlequin, and always the smartest person in the room. She was usually the only person seen on stage without a mask or clown make-up.

Pierrot (a/k/a Pagliacci) - a clown who somehow got Columbine to marry him. In the 18th century, he (almost) gave up Columbine, because he had his own Pierrette. But Pierrette often died young, leaving Pierrot always, always grieving - the sad clown.

Scaramouche - a clown, but "sly, adroit, and conceited". Later he became swashbuckling, mainly because of the Rafael Sabantini novel in which a swashbuckling nobleman's bastard hides out (in a plot twist) in a commedia troupe. BTW, the novel "Scaramouche" opens with the great line: "He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad."

Pulcinella a/k/a Punchinella a/k/a Punch (as in Punch and Judy) - a mean, crafty, hunchbacked clown who pretends to be stupider than he really is. He is also incredibly violent: with his "slapstick" (a stick as long as himself), he beats the living crap out of everyone, especially Judy.