As have so many of us, I've been following the case of the four Moscow, Idaho students (three women, one man) stabbed to death in their off-campus house in the middle of the night. When I first heard that the suspect was a criminology student, I thought of "Crime and Punishment". Roskolnikov was a young, handsome, intelligent law student who kills the old lady pawnbroker for money, and to prove that he is "exceptional", superior, like Napoleon.

Meanwhile, an old friend e-mailed "Leopold and Loeb", and that's a good comparison too. For those who haven't ever heard of them, L&L were two wealthy Chicago students who were obsessed with

Nietzsche's idea of the "Ubermensch", and came to believe that's what they were.

As Leopold wrote to Loeb, "A superman … is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do." So they decided to prove it.

They started out doing stupid petty thefts. They broke into a frat house and stole penknives, a camera, a typewriter (which they later used to write the ransom note). They got away with all of it, but the crimes were so minor that no one made much of a fuss, which wasn't what they wanted. They wanted to be recognized and, somehow, honored rather than held liable.

Anyway, theft wasn't doing the job, so they tried arson, but no one noticed that, either.

So they moved on to the next (to them) obvious thing to do: kill someone.

They spent the next few months planning the kidnapping and murder of 14 year old Bobby Franks, the son of wealthy Chicago watch manufacturer Jacob Franks. Bobby was also Loeb's second cousin.

NOTE: This would seem to prove that it's better to not be related to some people: as Augustus Caesar said, “It's better to be Herod's pig than his son.”

The two lured Franks into a rented car, killed him, mutilated his body, and dumped him at Wolf Lake, outside of Chicago. Then they called the family and said a ransom note was coming. And that's when everything went off the rails: first a nervous family member forgot the address of the store where he was supposed to receive the next set of directions. Then Bobby Franks' body was found.

Loeb went about his daily routine, but Superman (all ego, no tights) Leopold went around offering theories to anyone who would listen. He even told one detective, "If I were to murder anybody, it would be just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks."

And, even before DNA, the police found evidence: The typewriter. The car. Leopold's eyeglasses in the car. And an eyewitness to Loeb driving and Leopold in the back seat.

It became "the trial of the century", mainly because Loeb's family hired the attorney of the century, Clarence Darrow* to defend their boy. Darrow took the case because he was a staunch opponent of capital punishment, and the first thing he did was entered a plea of guilty on their behalf in hopes of getting them sentenced to life.

Darrow tried everything: the best testimony money could buy about the men's dysfunctional endocrine glands, psychiatric testimony about childhood neglect, absent parenting, sexual abuse (by a governess of Leopold's), and Leopold's claim that he and Loeb were lovers.

In the end, Darrow gave a 12 hour speech that's been called the finest speech of his career, pleading their youth (they were 19 and 20 respectively), and their immaturity ("Is any blame attached because somebody took Nietzsche's philosophy seriously and fashioned his life upon it?"), and the judge sentenced them to life.

(Personally, I think it helped that they were white. I find it very hard to believe that a couple of young black men in the same situation would have gotten anything but the death penalty. If they even survived the arrest.)

|

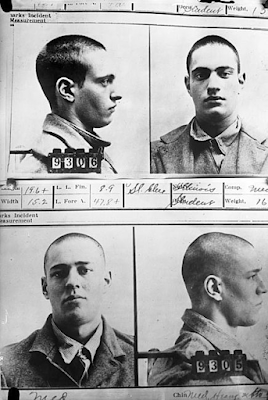

| Leopold & Loeb |

NOTE: Loeb ended up being killed in prison. Leopold eventually got parole in 1958, and moved to Puerto Rico, where he worked for The Brethren Service Commission, as a medical technician at its hospital. He went on to marry, get a master's degree, and do work in a variety of social services programs. (Wikipedia)

I don't know if the current suspect did the Idaho murders. I know that People magazine has some interesting reminiscences about him from his high school and college years: weight problems, bullying and being bullied, heroin addiction (and perhaps sales), a college contrarian who seemed to have problems with women, super curious, very intelligent, and a bit of a creep with the women at the local bar.

And then there's this:

Joey Famularo had Kohberger as a teaching assistant in one of her classes at Washington State and previously spoke about her experiences with him on TikTok. She recalled that Kohberger was a tough grader early in the semester, but that his behavior changed after Nov. 12, 2022, when the murders occurred.

She noted that there were no real red flags about him and that her class of 150 students "didn't see him very often," but explained, "after November 12th, his behavior changed significantly." Famularo noted that in October, Kohberger had failed all of his students on a test and left several comments on their work.

"Then starting November and December, he started just handing out 100s and leaving very minimal comments," she said. "So that was, I think, probably the biggest behavior change." (PEOPLE)

Yeah, that raises a bit of a red flag of something, doesn't it?

We'll all have to wait and see…

* Darrow went on the next year to defend the schoolteacher in the "Scopes Monkey Trial", where his sparring partner was William Jennings Bryan. Everything from vilification to hilarity ensued, but the main thing was endless publicity for all. It all sounds so modern…

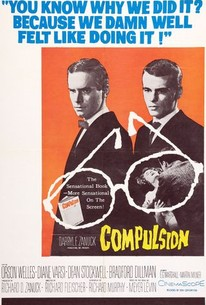

** Also, you could do worse than watch "Compulsion", the fictionalized version of the Leopold & Loeb case, starring Orson Welles (as the Clarence Darrow character), and Dean Stockwell and Bradford Dillman as the Leopold & Loeb characters. You can rent it on Amazon Prime or catch it on TCM.