Years ago, I gave my honors American Lit students a summer writing assignment that was a little outside the lines. I had them read Kerouac's On the Road and selections from Thoreau's Walden, then write the flogged-to-death essay on "What I Did on My Summer Vacation" twice, once imitating Kerouac's style and the other imitating Thoreau.

Some people did brilliantly, capturing Kerouac's riffs and imagery like a Wardell Gray sax solo and Thoreau's pseudo-King James majesty. Others wrote essays so interchangeable that I don't think the writers could have told me which was which.

We fail to teach students an important lesson about style. The style must fit the mood of the piece, which is determined by the content. If style, mood, and content don't work together, that story, essay, or letter will fail.

I can't find the quote now so I may be paraphrasing, but Sinclair Lewis once gave my favorite definition of style. Style is how the writer conveys emotion in his writing. It depends upon two factors: the ability to feel, and the vacabulary to express those feelings.

When readers say they don't like a book, they often mean that they don't like the style. Style is voice, and it carries the narrator's attitude and feelings about the material. If you don't like the feeling, it's fair to expect that you won't like the story.

How do you create style? You don't. You just write the truth about how you (or your story-teller) feels.

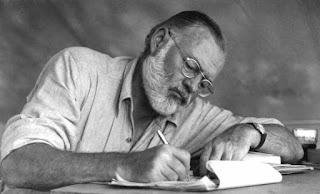

Extreme examples make it clearer. Read a paragraph by Ernest Hemingway and notice the generally short words a child can understand, combined into short punchy sentences that are equally clear. Hemingway could convey deep feelings and ideas, but in a deceptively simple style. It's hard to write so many short sentences without sounding choppy and abrasive, sort of like riding in a car when the transmission drops out. I see lots of writers try it and fail.

Now, read a paragraph from Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy. I have three graduate degrees and taught for over 30 years, but McCarthy often sent me to the dictionary. His words were always precise and conveyed his meaning more exactly than the synonyms I knew, and they never felt forced. McCarthy loved language and used it to serve his own purposes. I can't imagine anyone trying to imitate him.

Style is the way you use words to tell your story. We expect certain moods in certain kinds of stories, too. Noir writing is pessimistic. The weather is rainy or will be soon. Peopole will die and justice may not be served. Fairy tales usually have a happy ending and whatever ogres occupy the landscape may be frightening, but the hero will prevail with wit and courage.

The writer's job is to help the reader experience the events and emotions that the characters go through. It doesn't matter how clever or creative or beautiful the writer is. If the writing calls attention to that instead of the story, it fails.

Most of my writing is revision. I want the reader to see the events as my character sees and feels them, so I tend to use first person or detached third person POV and avoid opinion adjectives like "Nice," "Kind," "Beautiful" or "Evil" unles they get filtered through the character. Short stories don't have room for generalities, so it's vital to convey mood/attitude briefly. Mood matters. A few days ago, I decided a story I was writing for one publication didn't work because the story was supposed to be a cozy and the narrator was a gambler. Gamblers aren't cozy, they're noir.

Modern writers use more narration and less exposition than writers up until about 100 years ago. Think of long passsages of backstory and explanation in Dickens, Trollope, the Brontes or Hawthorne, then look at how Lehane, Lippman, Alison Gaylin or Don Winslow handles the same material.

I pinpoint the beginning of the change with Fitzgerald's description of the Buchanans' yard in chapter 1 of The Great Gatsby. Instead of static visual details, Fitzgerald makes the yard come to life so it runs from the beach, up the hill, jumps over a birdbath and sundial, and drifts up the walls of the house as "bright vines."

You can look at a picture as Hawthorne would describe it, but you can experience Tom and Daisy's yard. The average reader won't notice the difference, but he or she will feel it.

That's style at its best.