Those of us of a certain age discovered some great music in the 1980s. Before I drifted into jazz by way of progressive rock, my rock gods were Led Zeppelin and many of the bands that competed with them or followed in their footsteps. However, if you were raised in a household of a particular religious persuasion, you heard about it.

"That's devil music!"

In mom's defense, Jimmy Page was once a devotee of Aleister Crowley, whose hedonist creed used a lot of demonic imagery. Perhaps it didn't help when Zeppelin contemporary Ozzy Osbourne bit the head off a bat in concert. Or certain bands slapped pentagrams on their album covers. Eventually, I learned this was marketing, almost identical to slapping a Parental Advisory sticker on an album.

But that was not the real source of conflict. The real source came from parents watching the likes of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Jim and Tammy Fayre Bakker. All of them pushed one of the most dubious conspiracy theories ever devised: backward masking.

For the uninitiated, backward masking was an idea that backwards messages could be baked into the lyrics of a song. Repeated playings would register these messages in the subconscious and brainwash unsuspecting teens into devil cults. The idea gained credibility when someone stumbled onto the Beatles' "Revolution #9" containing the phrase "Turn me on, dead man" when the voice repeated "Number Nine" over and over. "Oh, my God! What are they saying? Paul is dead?" (1.) No, and even Pete Best thinks those who believe that are stupid, and 2.) "Revolution #9" is so clearly the result of an LSD trip that anything being intentional in it is almost as likely as NASA proving the Earth is flat.) The most notorious culprit came from Zeppelin itself, specifically, "Stairway to Heaven."

A tape circulated purporting to prove Zeppelin's masterpiece contained several of these backwards messages designed to send your children to Satan. (Cue evil laughter.) Except the tape was so clearly faked (like it didn't sound a thing like Robert Plant), and...

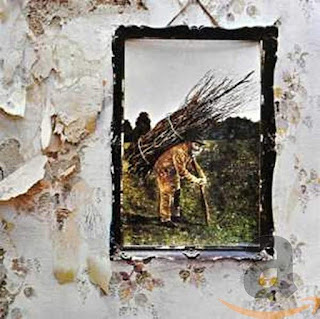

Your truly bought a cheap turntable to play vinyl, which was not as revered in the advent of CDs as it is now. It had a DC connector in an attempt by the manufacturer to force one to buy their receiver to play it through. Clever boy that I was, I bought an AC adapter and spliced the wires. I accidentally discovered that, if you reversed the polarity, the turntable would play records backward. And I owned a copy of Led Zeppelin IV. Spoiler alert: There are no backward messages on "Stairway." Zip. None. Nada. "And it makes me wonder" can be sounded out to "There is no escaping it." You're likely to find more meaning in "Turn me on, dead man."

That's not to say there wasn't a kernel of truth in the Satanic scare. In 1991, before I journeyed to Cincinnati to put down roots, I lived for six months near Shreve Swamp in Ohio's Amish Country. The swamps, for some reason, attracted devil worshipers. Not the hippie hedonists of Anton Levay's Churc of Satan. These teens, out to prove who knows what, sacrificed small animals to Old Scratch. They also liked an abandoned Dutch Reform Church cemetery near a house my parents rented one summer. Cemeteries, of course, attract all sorts of off-brand fringe religions. In the case of the cemetery, they went to school with my brother and his uber-religious classmates. My brother, being a cynic at an early age, amused himself by driving his car straight through one of their black masses. One of them threatened him at school the following week, to which my brother responded by doing his best Crazy Riggs from Lethal Weapon.

| |

| Warner Bros. |

But threats of curses and human sacrifice? There are places where it happens, but it's rare. But what about all those heavy metal pentagrams? James Hetfield of Metallica put it best. Metallica is a decidedly non-Satanic band. Dark imagery, maybe, but the Prince of Darkness doesn't really appear in their music. He said the pentagram told them it was heavy metal, and they should probably give it a listen to learn the craft. I'd say they succeeded.

What did I believe? I honestly got annoyed. By the time I discovered Zeppelin, I had most of the catalog of their rivals, Deep Purple. Zeppelin sounded like a more polished version of Purple, more flexible in their sound, and a tighter unit. Talk of backward messages to me was silliness, something an uncle has never forgiving me for debunking. It led me to Yes, which led to King Crimson, but it also led me to grunge and the alt rock of the 90s for me. Last I checked, I wasn't praying to the devil for untold riches, no matter how charming he is on Lucifer.