|

| Sherlock Ommmms |

The modern concept of mindfulness seems as far from Victorian England as Optimus Prime does from Robbie the Robot, yet maybe it's most ardent fictional practitioner shot out of that era like a bullet from a Webley Bulldog Revolver. Roughly 2300 years before the Victorian Age's namesake took the throne (and about 2420 years before The Kinks sang her praises in "Victoria"), the seeds of what we now call "mindfulness" started with Buddha himself, passing into the west largely through meditation, yoga, and for me as a kid, the TV show

Kung Fu.

The western medical community began picking up on these stress-reducing practices as an alternative to the drugs, booze, and all the other fun stuff we westerners use to to chill out. Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn was one of the first to do so and call it "mindfulness." "Mindfulness is awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally," said Kabat-Zinn. "And then I sometimes add, in the service of self-understanding and wisdom."

|

| Basil Rathbone being iconic |

|

| Jeremy Brett being brilliant |

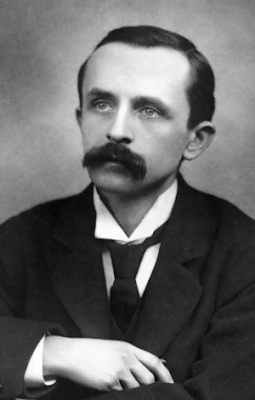

So who is this Victorian-era Buddha I mentioned earlier? His black shag tobacco is still sprinkled all over pop culture, one hundred and twenty-two years after he first appeared in print. We just can't seem to get enough Sherlock Holmes, be it in print, radio, theater, TV or movies. Holmes has been played by actors as varied as Basil Rathbone (my childhood favorite), Jeremy Brett (my all-time fav), Hammer Horror heroes Peter Cushing AND Christopher Lee, Robert Downey Jr, and Benedict Cumberbatch. Mr. Spock and Dr. House certainly share much of the Holmes DNA, as does last year's animated hit

Sherlock Gnomes. I bet if you looked long enough, you'd find Holmes porn floating around the internet. Please don't forward any links.

What is it about Holmes that still fascinates us? The knowledge, the reasoning, the

braininess of Holmes is what most consider Holmes' primary traits. Fans of the detective know there's so much more. Holmes' imagination, his ability to be

present and live utterly in the moment, his awareness of his own thought processes, his

mindfulness, are perhaps his greatest and most impressive gifts.

If Doyle meant the Holmes stories to be idle entertainment only, he was wildly successful. What if Doyle was also showing us a better way to live? Maria Konnikova thinks that's exactly what Doyle was doing, and she teaches us how to think like Sherlock Holmes in her fascinating manual-of-mindfulness

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes (2013)

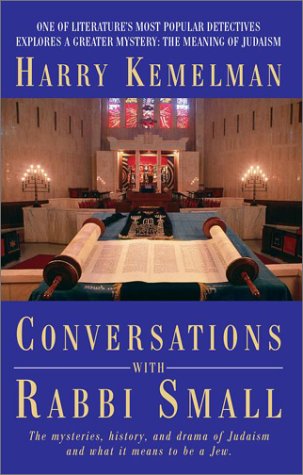

Maria Konnikova first caught the Holmes bug when her father read Holmes stories to her when she was little. She eventually earned her Ph.D. in psychology from Columbia and has published extensively about science, yet she owns up to the role that reading fiction has played in her life: "I think the best psychologists are actually fiction writers. Their understanding of the human mind is so far beyond where we've been able to get with psychology as a science."

Mastermind presents the two different ways in which people use their brains. There is the Watson system, which is our default system. The Watson system makes all the mental errors that Watson, Lestrade, and the rest of the bumblers make in the Holmes stories. The Watson system jumps to incorrect conclusions, is influenced by appearances, and isn't really paying attention, either to the outside world or to it's own mental workings.

The Holmes system will have none of that. By dent of effort, it takes the Watson system offline and installs a new operating system in our consciousness. "Checklists, formulas, structured procedures: those are your best bet,"

Mastermind explains. Through practice, habit, and the pursuit of mindfulness,

Mastermind claims that the Holmes system opens up a new world of thought: it forces us to be neutral in our observations; it cajoles us to be doubtful of first impressions and of our own minds; it commands us to be superior observers; it directs us to engage the world with all of our senses; it frees up our imaginations; it forbids multi-tasking and it demands focus on the job at hand. Be

present, it shouts, like a teacher to a student drifting off in class.

Mastermind backs up its precepts with science, and it can be a little dry. Having said that, I think Doyle (and Holmes) wouldn't have had it any other way. Konnikova digs into the science, but there is never any doubt that her inspiration for

Mastermind is the fiction of Doyle. I really enjoyed

Mastermind when it uses the Holmes stories to illustrate a point.

In

The Hound of the Baskervilles, Watson and Holmes take turns deducing the biographical details of Dr. James Mortimer by examining the absent doctor's walking stick. Watson makes his usual mistakes, and Holmes "embarks on his own logical

tour de force." Holmes goes on to deduce much about Dr. Mortimer's background, age, habits, ambitions, and pet ownership.

According to

Mastermind, this scene "brings together all of the elements of the scientific approach to thought that we've spent this book exploring and serves as a near-ideal jumping-off point for discussing how to bring the thought process together as whole." Some of the thought-practices Konnikova garners from this episode are: being aware of our environment; the value of thoughtful observation; and allowing the imagination, maybe the most powerful tool in our mental arsenal, to tangle with life's problems.

It wouldn't be fair to boil

Mastermind down to only one mental habit, but if forced to the edge of the Reichenbach Falls, I'd say it's the same exercise that's at the heart of mindfulness. "Holmes' mental journeying goes by many names, but most commonly it is called meditation," Konnikova writes. "Holmes is neither monk nor yoga practitioner," Konnikova adds, "but he understands what meditation, in its essence, actually is–– a simple mental exercise to clear your mind."

Konnikova argues that meditation trains our brains to be more Holmes-like. She discusses studies that show that meditation boosts concentration, learning, memory, and even brain density. Meditation "can help you create the right frame of mind to attain the distance necessary for mindful, imaginative thought."

I expect some eye rolls at this connection of Holmes and meditation, mindfulness, and anything that smacks of New Age mysticism. First I'd say that meditation has been moved out of the realms of eastern tradition and into medical practice by western science. Don't be put off if your MD prescribes a shot of meditation for what ills you, with a tai chi chaser.

The biggest complaint about

Mastermind could be that it's taking Sherlock Holmes too seriously. Doyle conjured the stories while his medical practice was slow, and surely he meant them only as idle entertainment. An argument could be made otherwise. Holmes is, after all, largely based on Dr. Joseph Bell, a professor at The University of Edinburgh Medical School who Doyle assisted. Bell was a doctor, a scientist, a teacher, and Doyle's mentor.

Like Holmes, Dr. Bell is purported to have had the skill of being able to tell a person's job just by looking at him. Bell once said "...we teachers find it useful to show the student how much a trained use of the observation can discover in ordinary matters such as the previous history, nationality and occupation of a patient." Perhaps Doyle is using Bell, a brilliant teacher, to create his own fictional teacher. After all, in

A Study in Scarlet, Holmes did write a magazine article on his methods for the public edification. He even gave it the rather self-important title "The Book of Life."

|

| Maria Konnikova calls your bluff |

After

Mastermind, Konnikova wrote

The Confidence Game (2016). In it she discusses the history of con artists and the reasons why people can be so easily duped. It's a great resource for crime writers, and a kind of sequel to

Mastermind and its mindfulness techniques. Though continuing to write, Konnikova is now a professional poker player. Considering her interests in Holmes, that should scare anyone with a handful of cards and secrets to hide.

|

Lawrence Maddox and Samuel Gailey

waiting to read at LA's Noir at the Bar |

Thanks to everyone who not only blew off one of the lamest Super Bowls ever, but also braved a stormy night to hit LA's Noir at the Bar at Mandrake. It was a great evening with myself, Gray Basnight, Eric Beetner, Samuel Gailey, Nadine Nettman and Wendall Thomas taking turns at the mic, and Eric Beetner and Steve Lauden hosting. Afterwards I somehow ended up clear across town at the Altadena Ale & Wine House discussing all things lit. See ya at the next one!