Mark Twain's essay, 'Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses,' is one of the more definitive take-downs, rude, exacting, and murderously funny. Twain's subject was always America, the American narrative and the American imagination. Cooper, for all his faults, is clearly the first American novelist. An infelicitous writer he may be, but he's more or less trying to invent a New World literature, and in this sense, we wouldn't have Twain if Cooper hadn't ploughed the ground beforehand. Twain means what he says about Cooper's stylistic clunkers ("use the right word, not its second cousin"), and certainly there's a generational difference, Cooper an inflated literary monument who's fallen out of fashion, Twain the more spirited and energetic voice, but Twain's real quarrel seems to be with the tradition of Romantic literature itself. Cooper's themes are vigorous, but his execution is lazy, and generic conventions sand off the rough edges. Twain argues for a greater muscularity.

Cooper's dates are 1789 to 1851. Sir Walter Scott's are 1771 to 1832. They're almost contemporaries. And you can see similarities, their discursiveness on the one hand, and too many easy outs on the other - what you might call the With-One-Gigantic-Leap school of hairbreadth escapes. (In all fairness, Scott is a much livelier and more inventive writer than Cooper; credit where credit is due.) I'm also bringing up Scott because Twain's got a score to settle with him, too. Twain wrote Life on the Mississippi some years after the fact, and although he has a soft spot for the river and its steamboat culture, he's not at all nostalgic for the slave economy of the prewar South, and he puts the blame for the elegiac folderol of the Lost Cause squarely on Walter Scott. Nor does he mean it as metaphor. Twain says expressly that the sentimental goop in Scott's romances - in particular Bonnie Prince Charlie and the failed Stuart uprising of 1745 - leads not only into the failed enterprise of Secession, but that it influences the historically revisionist nonsense that the slave states were some kind of agrarian Eden, unsullied by grasping capital and crude industrial instincts, a benevolent plantation economy, where the darkies of some mythic bygone age were happy to know their place.

Twain has no patience with this crap at all. Remember that he was born in Missouri twenty-five years before the Civil War, and was no stranger to slavery as a commonplace of everyday life. Twain seems to be the first American writer to integrate slavery (no pun intended) into the fabric of his fiction. I don't mean to scant Harriet Beecher Stowe, but Uncle Tom's Cabin is agitprop. It was enormously successful, at the time second in sales only to the Bible, but let's be honest, it's not seriously coherent, or anything like realistic. It rings every phony bell. If we take Twain's critical yardstick as a useful measure, Uncle Tom's Cabin is flabby, and Huckleberry Finn is muscular. Twain represents slavery as a constant in the social dynamic, it's simply there. Harriet Stowe preaches. Twain is more subversive. If slavery is the lie at the heart of America, the original sin, Twain disinherits our creation myth. This country wasn't founded on the altar of liberty, he tells us, it was established with a crime.

Huckleberry Finn is celebrated for its vivid invention: Miss Watson, a tolerable slim old maid, Moses and the Bullrushers, praying for fishhooks; Huck's escape from his father, his deceptions, disguises, and improvisations; the long, somnolent days adrift on the river; the abandoned boat, and the House of Death; the Grangerford feud, easily the single most terrifying episode of the book; the killing of Boggs, and the public shaming of the lynch mob; the horrifying vigilante violence that overtakes the Duke and the King; even its farcical ending, the over-elaborate plot to free Jim. What knits it all together, through its eventfulness and Quixotic structure, the shifting landscape of shore and water, is Huck's shifting internal landscape, his moral antagonisms. Jim is clearly human, Huck sees him as a person; but Jim is chattel, he belongs to somebody else. There's a moment when Jim talks about trying to rescue his wife and children from their new owner, and Huck is scandalized. Jim's talking about doing an injury to a man Huck doesn't even know - this is how Huck puts it to himself - stealing another man's property. The irony passes without being labored. Another example is that that Duke and the King can trade Jim off as a fugitive (he is, of course, having run away from Miss Watson), but it doesn't matter whether Jim is a particular fugitive, on a wanted poster. The fact that he's black, and on the loose, and nobody lays claim to him, is enough. He's guilty by virtue of who he is. Once they miss the confluence of the Mississippi and the Ohio at Cairo, the tip of Illinois, they're drifting into the Deep South. Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas. Jim's exposure is greater, his hope of rescue that much less. The comedy begins to sink, and the inevitable weight of despair settles on Huck's shoulders, a long-held, guilty secret.

For all that I recognize Huckleberry Finn as a great book - I agree with Hemingway, among others, that it is in fact the Great American Novel - Huckleberry Finn is not Twain's closing argument about slavery. That book would be Pudd'nhead Wilson, a novel Twain began as slapstick, or farce, but which descends into utter darkness, a bottomless sinkhole of cruelty and shame.

Pudd'nhead Wilson is a murder mystery, and it turns on themes of doubling. The two Italian twins, who appear to be working a parapsychology con, and the two boys switched at birth, Tom Driscoll and Valet de Chambre. The resolution depends on fingerprinting, very much a novelty at the time of the action, the mid-1800's. (Twain was fascinated by technology. A picture shows him in Nikola Tesla's lab.) By his own report, Twain started out with a comic premise. but the social savagery crowded out social satire, and the unresolved tensions of race, privilege, and clan loyalties are redeemed in brute violence.

The peculiar institution, a coinage of John C. Calhoun's, had by the 1880's become completely racialized, an American refinement. The practice of indentured servitude, common in colonial times, was by definition a term of indenture with a set expiration date or a buy-out price. But slavery was an inherited station; you were born into it, and would die as property. Your children, no less, were livestock. None of slavery's advocates made a secret of its racial foundation, and of course breeding was encouraged - slaves were a cash crop. The flip side of this, and generally accepted, was that slave women were used for sex by their white owners, and they got pregnant, and these children were born slaves, too. The high-yaller gal was appreciated for having her more African characteristics diluted.

By the time we get to Pudd'nhead Wilson - to clarify, Twain wrote the book in the 1890's, but the story takes place some fifty years earlier, before the Civil War - these racial norms are well established. Roxana, owned by the Driscolls, is one-sixteenth black, and nursemaid to Thomas Driscoll. Her boy Chambers has a white father (possibly Percy Driscoll, her master), and he's but one-thirty-second black, which still condemns him to slavery. He looks white; in fact, Chambers is almost indistinguishable from Tom, but born on the wrong side of the blanket. Roxy exchanges the babies. Her son grows up as heir to the Driscoll fortune, and Driscoll's son grows up in the slave quarters - that hint of the tarbrush is enough. Later in the story, when Roxy explains his clouded birth to her grown son, masquerading as Tom, and threatens to expose him, he eliminates the threat by selling his mother downriver to the Delta cotton fields. Nothing if not resourceful, Tom murders his uncle, and frames one of the visiting Italian twins for it. In the end, he's too clever by half, and the pretense unravels. The false Tom is himself sold on the auction block. The real Tom, raised as the slave Chambers, is restored to his family legacy, but he's neither fish nor fowl: he loses the one tribe he knows, the slave community, and can't assimilate as a white slave-holder. The well has been poisoned.

Twain seems to suggest that the false Tom is corrupted by privilege, although he doesn't quite come down on one side or the other, nature or nurture. In the story, race is destiny, but not in the sense that one boy has a sunny outlook because he's secretly white, and the other has a temperament tainted by residual blackness. Some of their character can only be hard-wired, some is learned behavior. Perhaps the slave Tom has a native innocence, or a talent for it, and Chambers, the spoiled child, enlarges into bullyhood. Twain is ambiguous on this score. He's unambiguous in saying that circumstance itself - the iron conventions, the conditions of life, the immobility - creates a fatal lack of choice. Tom and Chambers are bound to one another by blood debt; both of them are trapped.

The longer shadow cast by Pudd'nhead Wilson is historical, the dark bruise of our national grief, spreading underneath the skin. The most pernicious aspect of historical denial is selective memory, and the evasion of responsibility. Glamorizing the South in defeat, and pretending race wasn't at issue, allowed for lynch law and Jim Crow, disguised as state sovereignty. It may have been coded language, but it was unapologetic white supremacy.

Not addressing the buried past - the unburied past, as it happens - or underlying social frictions, stresses any political system. It's generally accepted that the unequal terms imposed on Germany at Versailles in 1919 led to economic ruin and the rise of Hitler. Weimar was too weak to contain the tensions between the Red factions and the revanchist Right that played out across Europe. Much the same happened after the second war, the sentiment that the German Army was stabbed in the back again, even though this time they didn't have any Jews left to blame it on.

We see something familiar, then, in the grievance politics of our dislocated present. The vocabulary is different, to a degree, but the clamor, the intemperance, the hardening of the arteries, echoes the slave state sympathies of John C. Calhoun and his uncompromising belligerence. We seem ready to revisit the Lost Cause, not through the rosy lens of Gone with the Wind, but with a constipated whiner who got pushed off the swings. "George Porgie, pudding and pie, kissed the girls and made them cry. When the boys came out to play, Georgie Porgie ran away."

The question is ownership. Who controls the narrative? If we surrender the narrative, somebody else tells the story. Twain's lesson is that we can recover it, but we have to trust an unreliable narrator, a device as old as Homer. So we listen to our hearts. The rest is noise.

Showing posts with label American Civil War. Show all posts

Showing posts with label American Civil War. Show all posts

12 August 2020

Pudd'nheads

Labels:

American Civil War,

David Edgerley Gates,

Great American Novel,

Huckleberry Finn,

James Fenimore Cooper,

Mark Twain,

Sir Walter Scott,

slavery

21 June 2020

Statues of Limitations

by Leigh Lundin

In the initial wave of Black Lives Matter, I was astonished how many moderates misunderstood the message, good-hearted but befuddled people who responded with “All lives matter.” The debate reminded me of a marital argument where husband and wife talk past one another, those moments when she just wants him to listen.

I hope it still doesn’t need spelling out, but supporting Black Lives Matter is hardly tantamount to, say, embracing the Black Liberation Army, that mirror image of the White Aryan Resistance.

Yes, of course all lives matter, but realize BLM is literally an existential issue for black folks, and by existential, I mean life…and…death. This year more people– not everyone but an accelerating number– begin to understand marginalization and how tenuous the life of a black man can be. I still haven’t got past the killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice playing by himself in a Cleveland park on a snowy day. There’s no rationale, man.

Feet of Clay

A professional photographer I knew said, “The Klan does a lot of good. You know they feed children.”

“To what?” I said.

I’m not sure he got it. Hitler liked children too, very, very white ones.

Ten days ago, Brian Thornton wrote about monuments, D.W. Griffith, and the sanitizing and romanticizing of slavery in this country. I commented that a Jacksonville, Florida school only recently changed its name from that of a founder of the Ku Klux Klan.

Perhaps a balance should be sought about the value, equitability, and fairness of controversial statuary. A soldier doing his job, maybe. A murderous jayhawker or bushwhacker, nooooo. A founder of the KKK, nooooo, decidedly not. Just a thought.

Feat of Kaolin

Brian also mentioned Shelley’s poem ‘Ozymandias’, which reminded me of a great short story by Oscar Wilde, one I thought infinitely sad when I was a small child.

In that classics spirit set forth by Brian, here is Wilde’s fable…

I hope it still doesn’t need spelling out, but supporting Black Lives Matter is hardly tantamount to, say, embracing the Black Liberation Army, that mirror image of the White Aryan Resistance.

Yes, of course all lives matter, but realize BLM is literally an existential issue for black folks, and by existential, I mean life…and…death. This year more people– not everyone but an accelerating number– begin to understand marginalization and how tenuous the life of a black man can be. I still haven’t got past the killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice playing by himself in a Cleveland park on a snowy day. There’s no rationale, man.

Feet of Clay

A professional photographer I knew said, “The Klan does a lot of good. You know they feed children.”

“To what?” I said.

I’m not sure he got it. Hitler liked children too, very, very white ones.

Ten days ago, Brian Thornton wrote about monuments, D.W. Griffith, and the sanitizing and romanticizing of slavery in this country. I commented that a Jacksonville, Florida school only recently changed its name from that of a founder of the Ku Klux Klan.

|

| The Happy Prince © Morry |

Feat of Kaolin

Brian also mentioned Shelley’s poem ‘Ozymandias’, which reminded me of a great short story by Oscar Wilde, one I thought infinitely sad when I was a small child.

In that classics spirit set forth by Brian, here is Wilde’s fable…

The Happy Prince

by Oscar Wilde

Labels:

American Civil War,

free story,

Leigh Lundin,

Oscar Wilde

Location:

USA

21 December 2017

James Thurber Strikes Again

by Eve Fisher

Although technically, this is by James Thurber. And has an odd connection to a very famous Christmas poem - see if you can spot it!

("Scribner's" magazine is publishing a series of three articles: "If Booth Had Missed Lincoln," "If Lee Had Won the Battle of Gettysburg," and "If Napoleon Had Escaped to America." This is the fourth.)

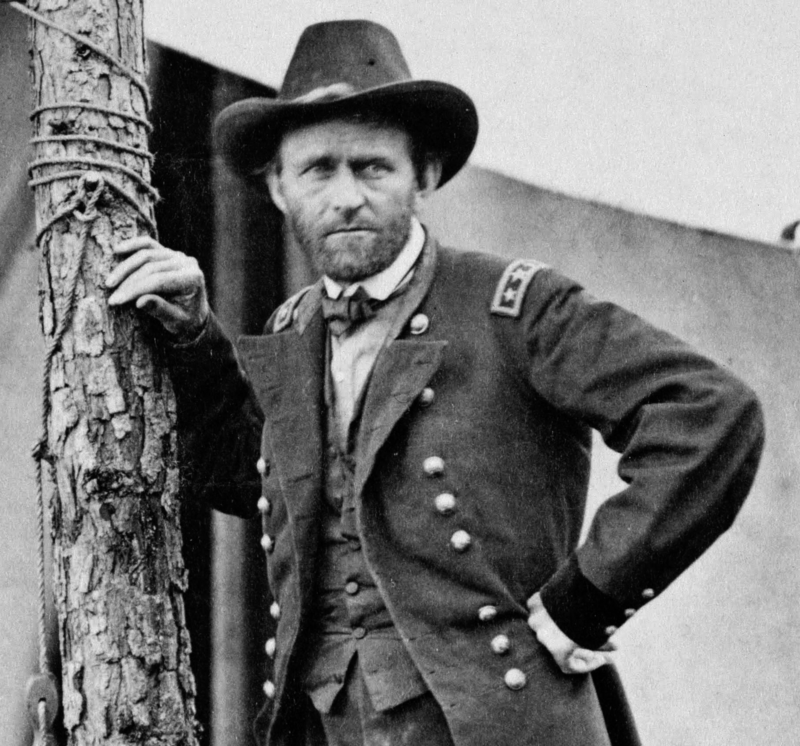

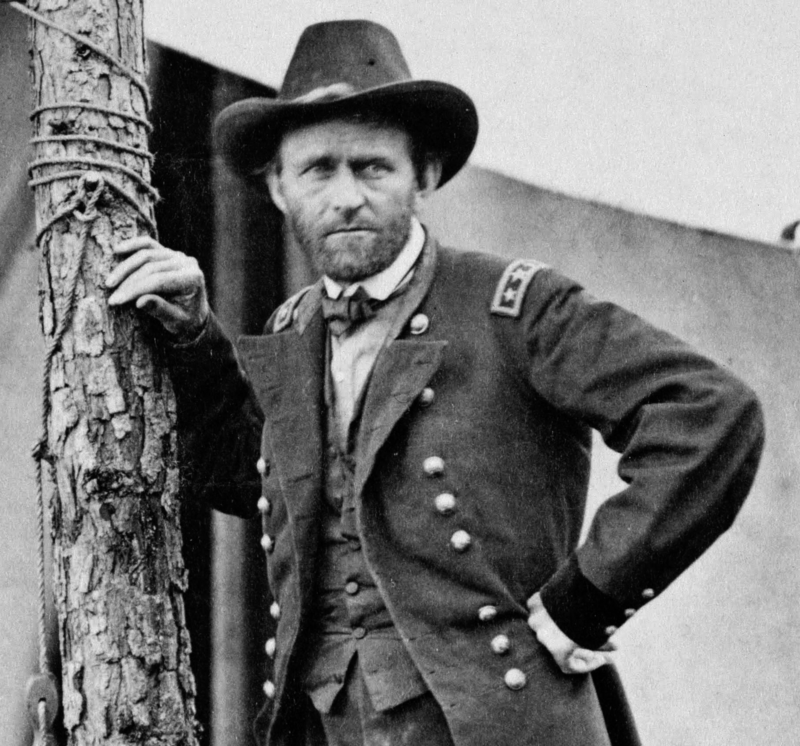

The morning of the ninth of April, 1865, dawned beautifully. General Meade was up with the first streaks of crimson in the sky. General Hooker and General Burnside were up and had breakfasted, by a quarter after eight. The day continued beautiful. It drew on. toward eleven o'clock. General Ulysses S. Grant was still not up. He was asleep in his famous old navy hammock, swung high above the floor of his headquarters' bedroom. Headquarters was distressingly disarranged: papers were strewn on the floor; confidential notes from spies scurried here and there in the breeze from an open window; the dregs of an overturned bottle of wine flowed pinkly across an important military map.

The morning of the ninth of April, 1865, dawned beautifully. General Meade was up with the first streaks of crimson in the sky. General Hooker and General Burnside were up and had breakfasted, by a quarter after eight. The day continued beautiful. It drew on. toward eleven o'clock. General Ulysses S. Grant was still not up. He was asleep in his famous old navy hammock, swung high above the floor of his headquarters' bedroom. Headquarters was distressingly disarranged: papers were strewn on the floor; confidential notes from spies scurried here and there in the breeze from an open window; the dregs of an overturned bottle of wine flowed pinkly across an important military map.

Corporal Shultz, of the Sixty-fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, aide to General Grant, came into the outer room, looked around him, and sighed. He entered the bedroom and shook the General's hammock roughly. General Ulysses S. Grant opened one eye.

"Pardon, sir," said Corporal Shultz, "but this is the day of surrender. You ought to be up, sir."

"Don't swing me," said Grant, sharply, for his aide was making the hammock sway gently. "I feel terrible," he added, and he turned over and closed his eye again.

"General Lee will be here any minute now," said the Corporal firmly, swinging the hammock again.

"Will you cut that out?" roared Grant. "D'ya want to make me sick, or what?" Shultz clicked his heels and saluted. "What's he coming here for?" asked the General.

"This is the day of surrender, sir," said Shultz. Grant grunted bitterly.

"Three hundred and fifty generals in the Northern armies," said Grant, "and he has to come to me about this. What time is it?". "You're the Commander-in-Chief, that's why," said Corporal Shultz. "It's eleven twenty, sir."

"Don't be crazy," said Grant. "Lincoln is the Commander-in-Chief. Nobody in the history of the world ever surrendered before lunch. Doesn't he know that an army surrenders on its stomach?" He pulled a blanket up over his head and settled himself again.

"The generals of the Confederacy will be here any minute now," said the Corporal. "You really ought to be up, sir." Grant stretched his arms above his head and yawned. "All right, all right," he said. He rose to a sitting position and stared about the room. "This place looks awful," he growled. "You must have had quite a time of it last night, sir," ventured Shultz. "Yeh," said General Grant, looking around for his clothes. "I was wrassling some general. Some general with a beard."

"The generals of the Confederacy will be here any minute now," said the Corporal. "You really ought to be up, sir." Grant stretched his arms above his head and yawned. "All right, all right," he said. He rose to a sitting position and stared about the room. "This place looks awful," he growled. "You must have had quite a time of it last night, sir," ventured Shultz. "Yeh," said General Grant, looking around for his clothes. "I was wrassling some general. Some general with a beard."

Shultz helped the commander of the Northern armies in the field to find his clothes. "Where's my other sock?" demanded Grant. Shultz began to look around for it. The General walked uncertainly to a table and poured a drink from a bottle. "I don't think it wise to drink, sir," said Shultz. Nev' mind about me," said Grant, helping himself to a second, "I can take it or let it alone. Didn' ya ever hear the story about the fella went to. Lincoln to complain about me drinking too much? 'So-and-So says Grant drinks too much,' this fella said. 'So-and-So is a fool,' said Lincoln. So this fella went to What's-His-Name and told him what Lincoln said and he came roarin' to Lincoln about it. 'Did you tell So-and-So was a fool?' he said. 'No,' said Lincoln, 'I thought he knew it.'" The'General smiled, reminiscently, and had another drink. ""That's how I stand with Lincoln," he said, proudly,

The soft thudding sound of horses' hooves came through the open window. Shultz hurriedly walked over and looked out. "Hoof steps," said Grant, with a curious chortle. "It is General Lee and his staff," said Shultz. "Show him in," said the General, taking another drink. "And see what the boys in the back room will have." Shultz walked smartly over to the door, opened it, saluted, and stood aside.

General Lee, dignified against the blue of the April sky, magnificent in his dress uniform, stood for a moment framed in the doorway. He walked in, followed by his staff. They bowed, and stood silent. General Grant stared at them. He only had one boot on and his jacket was unbuttoned.

"I know who you are," said Grant.'You're Robert Browning, the poet." "This is General Robert E. Lee," said one of his staff, coldly. "Oh," said Grant. "I thought he was Robert Browning. He certainly looks like Robert Browning. There was a poet for you. Lee: Browning. Did ya ever read 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix'? 'Up Derek, to saddle, up Derek, away; up Dunder, up Blitzen, up, Prancer, up Dancer, up Bouncer, up Vixen, up -'".

"I know who you are," said Grant.'You're Robert Browning, the poet." "This is General Robert E. Lee," said one of his staff, coldly. "Oh," said Grant. "I thought he was Robert Browning. He certainly looks like Robert Browning. There was a poet for you. Lee: Browning. Did ya ever read 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix'? 'Up Derek, to saddle, up Derek, away; up Dunder, up Blitzen, up, Prancer, up Dancer, up Bouncer, up Vixen, up -'".

"Shall we proceed at once to the matter in hand?" asked General Lee, his eyes disdainfully taking in the disordered room. "Some of the boys was wrassling here last night," explained Grant. "I threw Sherman, or some general a whole lot like Sherman. It was pretty dark." He handed a bottle of Scotch to the commanding officer of the Southern armies, who stood holding it, in amazement and discomfiture. "Get a glass, somebody," said Grant, .looking straight at General Longstreet. "Didn't I meet you at Cold Harbor?" he asked. General Longstreet did not answer.

"I should like to have this over with as soon as possible," said Lee. Grant looked vaguely at Shultz, who walked up close to him , frowning. "The surrender, sir, the surrender," said Corporal Shultz in a whisper. "Oh sure, sure," said Grant. He took another drink. "All right," he said. "Here we go."

Slowly, sadly, he unbuckled his sword. Then he handed it to the astonished Lee. "There you are. General," said Grant. "We dam' near licked you. If I'd been feeling better we would of licked you."

My friends, enjoy, two videos of this classic:

One, the Drunk-A-Vox recording of If Grant Had Been Drinking at Appomattox aloud (and how appropriate that is!);

Two, a video production of the same, directed by David Bowler, starring Dave Forshtay: You Tube Version

The 1946 movie version of Twas the Night Before Christmas!

IF GRANT HAD BEEN DRINKING AT APPOMATTOX -James Thurber

("Scribner's" magazine is publishing a series of three articles: "If Booth Had Missed Lincoln," "If Lee Had Won the Battle of Gettysburg," and "If Napoleon Had Escaped to America." This is the fourth.)

The morning of the ninth of April, 1865, dawned beautifully. General Meade was up with the first streaks of crimson in the sky. General Hooker and General Burnside were up and had breakfasted, by a quarter after eight. The day continued beautiful. It drew on. toward eleven o'clock. General Ulysses S. Grant was still not up. He was asleep in his famous old navy hammock, swung high above the floor of his headquarters' bedroom. Headquarters was distressingly disarranged: papers were strewn on the floor; confidential notes from spies scurried here and there in the breeze from an open window; the dregs of an overturned bottle of wine flowed pinkly across an important military map.

The morning of the ninth of April, 1865, dawned beautifully. General Meade was up with the first streaks of crimson in the sky. General Hooker and General Burnside were up and had breakfasted, by a quarter after eight. The day continued beautiful. It drew on. toward eleven o'clock. General Ulysses S. Grant was still not up. He was asleep in his famous old navy hammock, swung high above the floor of his headquarters' bedroom. Headquarters was distressingly disarranged: papers were strewn on the floor; confidential notes from spies scurried here and there in the breeze from an open window; the dregs of an overturned bottle of wine flowed pinkly across an important military map.Corporal Shultz, of the Sixty-fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, aide to General Grant, came into the outer room, looked around him, and sighed. He entered the bedroom and shook the General's hammock roughly. General Ulysses S. Grant opened one eye.

"Pardon, sir," said Corporal Shultz, "but this is the day of surrender. You ought to be up, sir."

"Don't swing me," said Grant, sharply, for his aide was making the hammock sway gently. "I feel terrible," he added, and he turned over and closed his eye again.

"General Lee will be here any minute now," said the Corporal firmly, swinging the hammock again.

"Will you cut that out?" roared Grant. "D'ya want to make me sick, or what?" Shultz clicked his heels and saluted. "What's he coming here for?" asked the General.

"This is the day of surrender, sir," said Shultz. Grant grunted bitterly.

"Three hundred and fifty generals in the Northern armies," said Grant, "and he has to come to me about this. What time is it?". "You're the Commander-in-Chief, that's why," said Corporal Shultz. "It's eleven twenty, sir."

"Don't be crazy," said Grant. "Lincoln is the Commander-in-Chief. Nobody in the history of the world ever surrendered before lunch. Doesn't he know that an army surrenders on its stomach?" He pulled a blanket up over his head and settled himself again.

"The generals of the Confederacy will be here any minute now," said the Corporal. "You really ought to be up, sir." Grant stretched his arms above his head and yawned. "All right, all right," he said. He rose to a sitting position and stared about the room. "This place looks awful," he growled. "You must have had quite a time of it last night, sir," ventured Shultz. "Yeh," said General Grant, looking around for his clothes. "I was wrassling some general. Some general with a beard."

"The generals of the Confederacy will be here any minute now," said the Corporal. "You really ought to be up, sir." Grant stretched his arms above his head and yawned. "All right, all right," he said. He rose to a sitting position and stared about the room. "This place looks awful," he growled. "You must have had quite a time of it last night, sir," ventured Shultz. "Yeh," said General Grant, looking around for his clothes. "I was wrassling some general. Some general with a beard."Shultz helped the commander of the Northern armies in the field to find his clothes. "Where's my other sock?" demanded Grant. Shultz began to look around for it. The General walked uncertainly to a table and poured a drink from a bottle. "I don't think it wise to drink, sir," said Shultz. Nev' mind about me," said Grant, helping himself to a second, "I can take it or let it alone. Didn' ya ever hear the story about the fella went to. Lincoln to complain about me drinking too much? 'So-and-So says Grant drinks too much,' this fella said. 'So-and-So is a fool,' said Lincoln. So this fella went to What's-His-Name and told him what Lincoln said and he came roarin' to Lincoln about it. 'Did you tell So-and-So was a fool?' he said. 'No,' said Lincoln, 'I thought he knew it.'" The'General smiled, reminiscently, and had another drink. ""That's how I stand with Lincoln," he said, proudly,

The soft thudding sound of horses' hooves came through the open window. Shultz hurriedly walked over and looked out. "Hoof steps," said Grant, with a curious chortle. "It is General Lee and his staff," said Shultz. "Show him in," said the General, taking another drink. "And see what the boys in the back room will have." Shultz walked smartly over to the door, opened it, saluted, and stood aside.

General Lee, dignified against the blue of the April sky, magnificent in his dress uniform, stood for a moment framed in the doorway. He walked in, followed by his staff. They bowed, and stood silent. General Grant stared at them. He only had one boot on and his jacket was unbuttoned.

"I know who you are," said Grant.'You're Robert Browning, the poet." "This is General Robert E. Lee," said one of his staff, coldly. "Oh," said Grant. "I thought he was Robert Browning. He certainly looks like Robert Browning. There was a poet for you. Lee: Browning. Did ya ever read 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix'? 'Up Derek, to saddle, up Derek, away; up Dunder, up Blitzen, up, Prancer, up Dancer, up Bouncer, up Vixen, up -'".

"I know who you are," said Grant.'You're Robert Browning, the poet." "This is General Robert E. Lee," said one of his staff, coldly. "Oh," said Grant. "I thought he was Robert Browning. He certainly looks like Robert Browning. There was a poet for you. Lee: Browning. Did ya ever read 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix'? 'Up Derek, to saddle, up Derek, away; up Dunder, up Blitzen, up, Prancer, up Dancer, up Bouncer, up Vixen, up -'"."Shall we proceed at once to the matter in hand?" asked General Lee, his eyes disdainfully taking in the disordered room. "Some of the boys was wrassling here last night," explained Grant. "I threw Sherman, or some general a whole lot like Sherman. It was pretty dark." He handed a bottle of Scotch to the commanding officer of the Southern armies, who stood holding it, in amazement and discomfiture. "Get a glass, somebody," said Grant, .looking straight at General Longstreet. "Didn't I meet you at Cold Harbor?" he asked. General Longstreet did not answer.

"I should like to have this over with as soon as possible," said Lee. Grant looked vaguely at Shultz, who walked up close to him , frowning. "The surrender, sir, the surrender," said Corporal Shultz in a whisper. "Oh sure, sure," said Grant. He took another drink. "All right," he said. "Here we go."

Slowly, sadly, he unbuckled his sword. Then he handed it to the astonished Lee. "There you are. General," said Grant. "We dam' near licked you. If I'd been feeling better we would of licked you."

My friends, enjoy, two videos of this classic:

One, the Drunk-A-Vox recording of If Grant Had Been Drinking at Appomattox aloud (and how appropriate that is!);

Two, a video production of the same, directed by David Bowler, starring Dave Forshtay: You Tube Version

The 1946 movie version of Twas the Night Before Christmas!

And a Merry Christmas to All!!!!

Labels:

American Civil War,

Appomattox,

Eve Fisher,

General Ulysses S. Grant,

James Thurber,

Robert E. Lee

30 November 2016

Writing for Whackademia

When Leigh - or was it Velma? - suggested a theme week about writing for non-mystery magazines, I said I could contibute nothing. Then I realized that if you include academic journals I have a bit to say.

You have probably heard of "publish or perish," the idea that college faculty have to do research to get tenure and keep their jobs. And you are right. The intensity depends on the field and the institution. I know people who are expected to publish several short articles a year, and others whose job security hangs on making it into certain major journals.

Fortunately neither of those apply to me, but I am expected to appear in scholarly journals. So what's the difference between one of those and a magazine? At the most basic, a scholarly (or academic, or peer-reviewed, or refereed... they all mean essentially the same thing) journal is one where, rather than deciding on the fate of an article herself, the editor sends it to people who have written on similar subjects (peers) for their assessment.

This is considered the gold-standard, the most reliable and authorative type of publication. And having said that, let me introduce you to Retraction Watch, a website that simply lists scholarly articles that have been renounced by their authors or publishers because of errors. These errors could be anything from deliberate fraud to an accidentally screwed-up graph. Some authors have been known to retract an article because, decades after publication, the science turned out to be wrong.

And don't forget Scholarly Open Access, a website created by librarian Jeffrey Beall, which reports on what he calls "predatory journals," which look like scholarly

material, but will accept anything you will pay them to publish.

"Vanity publishing!" you shout. Well, yes. But it's more complicated

than that because in some academic fields you are expected to pay a per-page fee for publication - or at least if you want the article to be "open access," so anyone can read it. It is so common that many universities have funds to pay for their professors page fees. Or if a grant pays for your research, you can figure it into the grant request. But the non-predator journals still reject most articles that are submitted, and won't take your fee until their referees have reviewed your work.

And don't forget Scholarly Open Access, a website created by librarian Jeffrey Beall, which reports on what he calls "predatory journals," which look like scholarly

material, but will accept anything you will pay them to publish.

"Vanity publishing!" you shout. Well, yes. But it's more complicated

than that because in some academic fields you are expected to pay a per-page fee for publication - or at least if you want the article to be "open access," so anyone can read it. It is so common that many universities have funds to pay for their professors page fees. Or if a grant pays for your research, you can figure it into the grant request. But the non-predator journals still reject most articles that are submitted, and won't take your fee until their referees have reviewed your work.

If you have begun to suspect that publishing scholarly journals is a license to mint money, there are many who will agree with you.

Let's get to a few of my own experiences in the field. Many years ago I did some research which I thought was interesting but probably not worth a publication, so I put it up on a webpage of my own. The managing editor of an editor read my work and invited me to turn it into an article for his journal. Great! I updated the info and submitted it, and waited.

And waited. And waited. Eventually (I think a year later) the editor-in-chief contacted me to say he had found the manuscript stuck in a desk drawer. If I wanted to update it again and resubmit it he would consider it (!).

Another time I felt obliged to explain to the committee who was evaluating my work for, say, 2011, that the reason I included an article published in a 2010 journal issue was that the publisher had been running late and slapped the wrong date on so a year would not be missing from the journal's run. And yes, these were both considered respectable publishers.

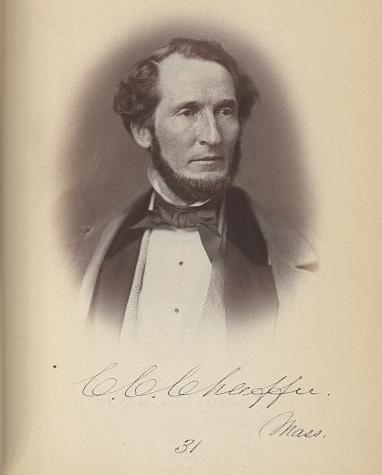

But my favorite story of scholarly hijinks involved the Congressional Serial Set. These books have been published since the 1830s and basically include reports to and from Congress. I found something very bizarre in one volume and showed it to my friend August A. Imholtz who is an expert on the Set. We wound up co-writing an article which was published under the name "'Reckless and Unwarranted Inferences': The US House Library Scandal of 1861." As befitted such a pompous title we wrote it with great seriousness and a flurry of footnotes.

As soon as it was published in a scholarly journal, with August's kind permission, I rewrote the same bit of history for laughs and sent it to American Libraries magazine which paid me for it (now that's the direction money is supposed to flow in publising) and put it up on their website with the title How Overdue Books Caused the Civil War.

You can read the lighter version by following the link above. In either version the story is this: After Lincoln was elected and southern states started to secede the New York Times published an article claiming that the southern ex-congressmen were stealing books from the "Congressional Library" to start their own. It turned out to be a mixture of wild gossip, bad journalism and shoddy library management. Oh, and it involves the Dred Scott Decision. Really.

Because when you dive into the academic swamp you never know what you will find.

You have probably heard of "publish or perish," the idea that college faculty have to do research to get tenure and keep their jobs. And you are right. The intensity depends on the field and the institution. I know people who are expected to publish several short articles a year, and others whose job security hangs on making it into certain major journals.

Fortunately neither of those apply to me, but I am expected to appear in scholarly journals. So what's the difference between one of those and a magazine? At the most basic, a scholarly (or academic, or peer-reviewed, or refereed... they all mean essentially the same thing) journal is one where, rather than deciding on the fate of an article herself, the editor sends it to people who have written on similar subjects (peers) for their assessment.

This is considered the gold-standard, the most reliable and authorative type of publication. And having said that, let me introduce you to Retraction Watch, a website that simply lists scholarly articles that have been renounced by their authors or publishers because of errors. These errors could be anything from deliberate fraud to an accidentally screwed-up graph. Some authors have been known to retract an article because, decades after publication, the science turned out to be wrong.

And don't forget Scholarly Open Access, a website created by librarian Jeffrey Beall, which reports on what he calls "predatory journals," which look like scholarly

material, but will accept anything you will pay them to publish.

"Vanity publishing!" you shout. Well, yes. But it's more complicated

than that because in some academic fields you are expected to pay a per-page fee for publication - or at least if you want the article to be "open access," so anyone can read it. It is so common that many universities have funds to pay for their professors page fees. Or if a grant pays for your research, you can figure it into the grant request. But the non-predator journals still reject most articles that are submitted, and won't take your fee until their referees have reviewed your work.

And don't forget Scholarly Open Access, a website created by librarian Jeffrey Beall, which reports on what he calls "predatory journals," which look like scholarly

material, but will accept anything you will pay them to publish.

"Vanity publishing!" you shout. Well, yes. But it's more complicated

than that because in some academic fields you are expected to pay a per-page fee for publication - or at least if you want the article to be "open access," so anyone can read it. It is so common that many universities have funds to pay for their professors page fees. Or if a grant pays for your research, you can figure it into the grant request. But the non-predator journals still reject most articles that are submitted, and won't take your fee until their referees have reviewed your work.If you have begun to suspect that publishing scholarly journals is a license to mint money, there are many who will agree with you.

Let's get to a few of my own experiences in the field. Many years ago I did some research which I thought was interesting but probably not worth a publication, so I put it up on a webpage of my own. The managing editor of an editor read my work and invited me to turn it into an article for his journal. Great! I updated the info and submitted it, and waited.

And waited. And waited. Eventually (I think a year later) the editor-in-chief contacted me to say he had found the manuscript stuck in a desk drawer. If I wanted to update it again and resubmit it he would consider it (!).

Another time I felt obliged to explain to the committee who was evaluating my work for, say, 2011, that the reason I included an article published in a 2010 journal issue was that the publisher had been running late and slapped the wrong date on so a year would not be missing from the journal's run. And yes, these were both considered respectable publishers.

| |

| Calvin C. Chaffee, House librarian, and luckless hero of my article. |

As soon as it was published in a scholarly journal, with August's kind permission, I rewrote the same bit of history for laughs and sent it to American Libraries magazine which paid me for it (now that's the direction money is supposed to flow in publising) and put it up on their website with the title How Overdue Books Caused the Civil War.

You can read the lighter version by following the link above. In either version the story is this: After Lincoln was elected and southern states started to secede the New York Times published an article claiming that the southern ex-congressmen were stealing books from the "Congressional Library" to start their own. It turned out to be a mixture of wild gossip, bad journalism and shoddy library management. Oh, and it involves the Dred Scott Decision. Really.

Because when you dive into the academic swamp you never know what you will find.

Labels:

academics,

American Civil War,

journals,

Lopresti,

writing

09 September 2015

Why We Fight, Pt. II

Last month, two U.S. Army officers, Capt. Kristen Griest and 1st Lt. Shaye Haver, were the first two women candidates to graduate Ranger school. This is an event to take pride in. Out of a field of four hundred, 25% made it. The others were washed out or set back, which gives you some idea how tough the course is. Not to diminish the effort they all made, but to suggest it's a steep gradient. A lot of us wouldn't qualify.

When the news broke, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee felt compelled to remark that the U.S. military isn't a social laboratory - they're meant to kill people and break things, is what he said. I take his point, but I think he's got it backwards. (He's also obviously taking a swipe at the retention of openly gay soldiers.)

In spite of being a deeply conservative, even intransigent, institution, the U.S. military has always been a social laboratory. The most intense combats we've fought are the Civil War and WWII, both of which brought enormous change. Viet Nam is of course a living memory to most of the people in my generation, but no matter how important it is, to us personally, and how divisive it was, to the country as a whole, I'm not sure it has as much historical significance as the other two. I could be proved

wrong. Viet Nam colors the thinking - strategic and political - of all our current senior commanders, and it's a perceived failure they don't want to see repeated. This leads to a kind of self-referential loop, or a fractured lens. It's a commonplace to say we're always fighting the last battle.

The point about the American Civil War, and the Second World War, is that they commanded near-total mobilization of men and resources. This is what sets them apart, in our experience. The machinery of the war effort was an engine that powered the new century. Few were left untouched by it. And then, afterwards, something similar happened both times. The peacetime Army drew down. It was more severe after the Civil War. 2 million men served under arms in the Union Army, and a million and a half fought for the Confederacy, but during the Indian Wars in the 1870's, the active-duty Army numbered no more than 30,000. WWII saw twelve million Americans serve. After demobilization, that figure dropped to a million-five.

The dislocations of war reflect broader social tensions and dislocations. To take one example, the Irish made up 10% of the Union Army - the Irish were also at the forefront of the New York draft riots, but they're a complicated clan - and a high proportion elected to stay in the military after the war ended. This at a time when professional soldiers were something of a despised class, and the Irish had a bad reputation to overcome, as well. It turned out to be a good career choice, in the main. More recently, although black GI's have served in every American war, there were few of them in combat during WWII, and that in segregated units, with white officers, but Truman fully integrated the services in 1948.

Women have played a supporting role - nurses and typists, although there were women pilots in WWII, not in combat, but ferrying resupply and aircraft into combat zones. The received wisdom being the usual boilerplate about upper body strength or lack of the warrior gene and all the rest, which still hasn't disappeared. Homosexuals have served with distinction, in spite of a prevailing locker room mentality. For that matter, so have Communist sympathizers and conscientious objectors.

In the end, it boils down to duty, not your politics, or your skin, or whether you sit down to pee. Lt. Haver and Capt. Griest have demonstrated that. They're the first but they won't be the last.

[This is a snapshot of my pal Michael Parnell, tired but happy, the day he himself completed Ranger training. I don't mean to make him self-conscious. He has every reason to be proud.]

http://www.davidedgerleygates.com/

When the news broke, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee felt compelled to remark that the U.S. military isn't a social laboratory - they're meant to kill people and break things, is what he said. I take his point, but I think he's got it backwards. (He's also obviously taking a swipe at the retention of openly gay soldiers.)

In spite of being a deeply conservative, even intransigent, institution, the U.S. military has always been a social laboratory. The most intense combats we've fought are the Civil War and WWII, both of which brought enormous change. Viet Nam is of course a living memory to most of the people in my generation, but no matter how important it is, to us personally, and how divisive it was, to the country as a whole, I'm not sure it has as much historical significance as the other two. I could be proved

wrong. Viet Nam colors the thinking - strategic and political - of all our current senior commanders, and it's a perceived failure they don't want to see repeated. This leads to a kind of self-referential loop, or a fractured lens. It's a commonplace to say we're always fighting the last battle.

The point about the American Civil War, and the Second World War, is that they commanded near-total mobilization of men and resources. This is what sets them apart, in our experience. The machinery of the war effort was an engine that powered the new century. Few were left untouched by it. And then, afterwards, something similar happened both times. The peacetime Army drew down. It was more severe after the Civil War. 2 million men served under arms in the Union Army, and a million and a half fought for the Confederacy, but during the Indian Wars in the 1870's, the active-duty Army numbered no more than 30,000. WWII saw twelve million Americans serve. After demobilization, that figure dropped to a million-five.

The dislocations of war reflect broader social tensions and dislocations. To take one example, the Irish made up 10% of the Union Army - the Irish were also at the forefront of the New York draft riots, but they're a complicated clan - and a high proportion elected to stay in the military after the war ended. This at a time when professional soldiers were something of a despised class, and the Irish had a bad reputation to overcome, as well. It turned out to be a good career choice, in the main. More recently, although black GI's have served in every American war, there were few of them in combat during WWII, and that in segregated units, with white officers, but Truman fully integrated the services in 1948.

Women have played a supporting role - nurses and typists, although there were women pilots in WWII, not in combat, but ferrying resupply and aircraft into combat zones. The received wisdom being the usual boilerplate about upper body strength or lack of the warrior gene and all the rest, which still hasn't disappeared. Homosexuals have served with distinction, in spite of a prevailing locker room mentality. For that matter, so have Communist sympathizers and conscientious objectors.

In the end, it boils down to duty, not your politics, or your skin, or whether you sit down to pee. Lt. Haver and Capt. Griest have demonstrated that. They're the first but they won't be the last.

[This is a snapshot of my pal Michael Parnell, tired but happy, the day he himself completed Ranger training. I don't mean to make him self-conscious. He has every reason to be proud.]

http://www.davidedgerleygates.com/

Labels:

American Civil War,

black soldiers,

David Edgerley Gates,

Rangers,

U.S. Army,

U.S. military,

women in combat,

World War II,

WWII

08 January 2012

The Brazilian Confederacy

by mystery guest

|

| Leighton Gage |

Leigh Lundin: When writers claim excitement introducing a guest article, you can expect a great deal of hyperbole. Not in this case.

A couple of years ago, a group of eight international mystery writers banded together to form the blog, Murder is Everywhere. I'd already met Michael Sears, Stanley Trollip, and Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, and I was pleased to read other contributors, especially today's guest, Leighton Gage.

Leighton Gage lives in a small town in Brazil and writes police procedurals set in that country. A Vine in the Blood, the latest installment in his Chief Inspector Mario Silva series, was called “irresistible” by the Toronto Globe and Mail. Coincidentally, that was the very same word the New York Times used to describe the previous book in his series, Every Bitter Thing. Vine also garnered a star from Publisher’s Weekly.

I touched base with Leighton about the time my AOL account crashed

and burned, but his daughter managed to send me a 'fita do Senhor do Bomfim', a ribbon I use as a

bookmark.

I touched base with Leighton about the time my AOL account crashed

and burned, but his daughter managed to send me a 'fita do Senhor do Bomfim', a ribbon I use as a

bookmark.Leighton created today's article, one I wish my mother, a student of American Civil War history, could read. Indeed, I felt a pleasant frisson of discovery when I first read this exciting bit of history by Leighton Gage.

The Brazilian Confederacy

One day, a couple of years ago, I was in an office in São Paulo chatting to a friend in English. A lady I didn’t know came up to us and joined in the conversation. She spoke with the dulcet tones of the American South, and I asked her where she was from.

“I was born here,” she said, meaning Brazil.

“Okay. Your parents, then?”

“Here. And my grandparents too.”

And then she told me the story of the Brazilian Confederates, which, Dear Reader, I’m now going to pass on to you:

After the War Between the States many families from the old South were left landless and destitute. They hated living under a conquering army of Yankees. They were looking for a way out.

|

| Dom Pedro II |

Many of them settled in the State of São Paulo in the towns of Americana and Santa Barbara D’Oeste. The name of the former is derived from the Portuguese for “Village of the Americans” and the latter is sometimes called the Norris colony, named after Colonel William Norris, a former senator from Alabama who was one of the founders.

|

| Col. Wm. Norris |

He's the gentleman in the photo at right. If you’re a Civil War buff, and would like to experience a vestige of the Old South, I suggest you go to Santa Barbara on the second Sunday in April. That’s when they hold a yearly party on the grounds of the cemetery. Yeah, that’s right, the cemetery, the one where all of those old confederates are buried.

You’ll find it behind the church that faces the square with the monument.

The folks in Santa Barbara really know how to stage a party.

|

| monument |

|

| close-up |

|

| Santa Barbara Church |

You can eat southern fried chicken, vinegar pie, chess pie and biscuits. Banjos are played. Confederate songs are sung. The women dress in pink and blue and wear matching ribbons in their hair.

|

| dining |

|

| dancing |

And, if you visit the church for the memorial services, you might even get to meet Becky Jones, who presides over the Association of Confederates.

Becky learned her English from her parents. They learned it from their parents. And so on. Prompted, she’ll tell you that (even) Damnyankees are welcome to the party, but they have to expect to be received differently than someone from the South.

She might tell you, too, about her grandmother, Mrs. MacKnight-Jones, who survived well into her nineties. Grandma learned from her parents never to call Abraham Lincoln by his name. In their household he was only referred to as "that man".

And that family tradition goes on until this very day.

Labels:

American Civil War,

Brazil,

Confederacy,

Leighton Gage

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)