A man named Karl who lived in Germany in the 19th Century was a jack-of-all-trades. A skinner at a local slaughterhouse. A dog catcher. A tax collector at a time when one literally went door to door collecting cash payments. And a night watchman. Anything to make ends meet.

|

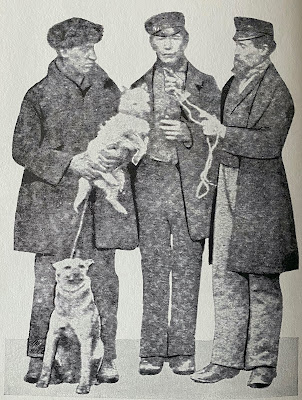

| Karl (left) with friends, canine and human. |

Karl needed to keep himself and the town’s funds safe as he strolled or patrolled the streets of the burgeoning industrial city of Apolda in Thuringia. Since Karl and his buddies loved dogs, and often frequented the city’s annual “dog market,” he hit upon the idea of breeding himself an animal to accompany him on his rounds. A four-footed security guard who would stick by his side and keep strangers at bay. A dog bred not for the field but for city streets. When Karl died in 1894, his canine-loving friends perfected that breed, which they named in honor of their departed friend, Karl Friedrich Louis

Dobermann.*

Cut to Summer 2019. I am standing at the edges of a decimated vegetable garden in North Carolina. Just as our veggies reach perfection, they become a banquet for the neighborhood’s rabbits and wild turkeys. The chief culprit is a groundhog who resides under our shed. Some days, I spot the plump marauder sunning itself in the yard. The effrontery! One day, I spot two.

“It’s a female!” I tell my wife. “She just had babies!”

Judging from the number of groundhogs we spotted over the ensuing years, Lady Whistle-Pig was popular with the gents.

One day, after surveying another truncated zucchini plant and chomped tomatoes, my wife announced, “We need a dog!”

I resisted. What do parents always tell their kids before bringing that puppy home? It’s a big responsibility. I wasn’t sure I wanted that. Except for the garden, I had perfected the art of sedentary living and marriage to my keyboard. A dog would wreck that.

Weeks passed, and Denise refined her requirements. We needed a smart dog. “I’m not going to have a stupid dog,” she said adamantly.

Two friends of hers had each recently gotten German shepherds, which appear prominently on lists of the world’s smartest breeds. These lists vary slightly, depending on who’s drawing them up. Anthropocentric to a fault, humans equate canine intelligence with trainability. The border collie is always No. 1, the standard poodle No. 2, the German shepherd No. 3. Also popular are golden retrievers (N0. 4) and Labrador retrievers (No. 7). The Australian cattle dog always makes the list too, around No. 10. Damn smart dogs, the Aussies.

A friend of ours—

a canine and equine artist—dissuaded us from the German shepherd. “Do you like the idea of cleaning up rolling tumbleweeds of fur around your house?” he asked.

We didn’t.

He recommended a Dobie. As a former vet tech, he believed Herr Dobermann’s breed ticked three basic boxes: They were among the Top 10 intelligent breeds, usually ranking at No.5.

They were less unpredictably bitey than shepherds. They shed minuscule amounts of eyelash-sized hair. And as an artist well versed in canine anatomy he regarded them as drop-dead gorgeous.

I grew up in a family with dogs; a golden retriever and later a mutt. Like Archie Goodwin, I had formed the erroneous impression that all dogs loved me. It never occurred to me to ask someone, “Is your dog friendly?” before approaching them.

In short, I was an idiot, and remained so until the day a neighbor’s Rottweiler took me for a snack. As the dog’s jaws clamped on my wrist—I still have the scar—two thoughts occurred to me in quick succession:

- Gee, he’s strong enough to crush my wrist.

- Huh—I probably should be wary of dogs.

Getting a Doberman to protect one’s vegetables seemed like overkill. Any yapping canine would do. During the pandemic, I surfed the web to research Dobermans, which in my uninformed view were just as fearsome as the pooch that bit me.

I learned that Karl’s breed are the only dogs created for personal protection. He and his friends believed that they were breeding “police-soldier dogs.” In World War II, the breed became a dog of choice for the Germans and the U.S. Marines. The latter used them as cave explorers, messengers, scouts, and bomb-sniffers. Twenty-five dogs, mostly Dobies, lost their lives on Guam, where a regal statue of a reclining Doberman stands in the U.S. war dog cemetery there. (More on this story in a future post.) They served as police dogs, too, until police forces moved on to breeds like German shepherds and the Belgian Malinois.

Doberman fanciers and police dog handlers love to pontificate on the reasons for that shift. Dobies have short coats, they say, so they aren’t great for outdoor police work in cold or hot weather. Taping their ears so they grow into the “correct” position is time-consuming. The dogs are too independent. They take too long to mature. Their bite style—bite and shred—makes them undesirable compared to shepherds, who bite and hold a suspect until they can be formally arrested.

On forums frequented by police dog handlers, people insist Euro-dobies are tougher animals. The European Dobermann is bigger and beefier. The American is more gracile. In their zeal to breed a safe family pet, goes the argument, Americans have winnowed the dogs’ natural aggression out of them. Breeders have created animals for show, not street work as originally intended. The American dogs were Little Lord Fauntleroys compared to der Dobermannpinscher.

Which sounded fine to me. It comforted me to see videos of American Dobermans patiently enduring the hugs of human toddlers, babysitting infants in swings, playing in kiddie pools, and serving as therapy and seeing-eye dogs.

Okay, I told Denise, let’s try to get a sit with some breeders. But that became impossible in 2020, when breeders halted their programs for fear that their animals would contract Covid-19 from prospective adopters, or vice versa. I gave up trying. It seemed like a pain in my tailless rump.

So when Denise revisited the dog issue again last summer, I told her we should select a rescue dog from the local shelter. Getting the eyelash-shedding dog of her dreams was unlikely to ever happen. Breeders required you to submit an application to judge your suitability. Did we have a yard that was completely fenced? (No.) Did we have experience taping Doberman ears? (No.) Had we thoroughly researched the dog ordinances in our municipality? (Um, what?) Sheesh.

“It’s way too complicated,” I said.

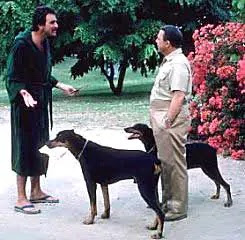

In early June 2022, we were sitting outdoors, again surveying our trampled garden. Denise peeked at the web on her phone for about three minutes, dialed a number, and in a matter of minutes was speaking with a lovely woman in South Carolina—three hours from our home—who had recently helped her champion female bring nine puppies into the world.

I am at heart a pessimist. If it was that easy to find a puppy, there had to be some catch. You don’t just pick a breeder off the web, I informed her, though that’s exactly what I had attempted to do in 2020. Turns out, she had unknowingly picked the oldest continuing Doberman kennel in the United States. A breeder whose late founder is mentioned lovingly in most textbooks on the breed. When the nine-pup litter was old enough to accept visitors, we drove south, and fell in love with one of the males. The kennel took a deposit, and promised to begin using with him the name we planned to bestow upon him.

I also learned that once in the kennel’s history, one of their dogs achieved fame prancing through the plotlines of this (fictional) detective’s adventures.

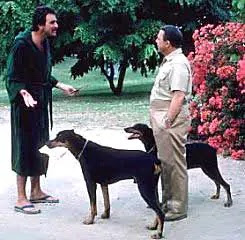

|

| Hillerman will always be Simon Brimmer to me. |

Well, shoot, I thought, I needed to break out my stash of Hawaiian shirts, and start growing a luxurious mustache. However, I wasn’t sure about sticking my ample keister into a pair of 70s-style short-shorts. But I had time to drop some weight; we would not be getting the dog for another six weeks.

While waiting, I dove back into the research. The breed was known for docked tails and cropped ears, to better reduce handholds for criminals. Ironically, in the 1980s European kennel clubs banned the practice of surgically altering dogs of any breed. They now regarded the practice as cruel and inhumane. Naturally, the erect ears and short tails remain the breed standard in the United States.

Hearing this, my own ears perked up. I had watched numerous videos on how to insert and wrap posts in my future puppy’s ears until his cartilage grew to support them in the customary position. We’d need to do this every five days, for 10 months at minimum. It looked daunting, fiddly, and prone to error.

We shot a note to the breeders. Please, oh pretty please, could we have our dog intact? The floppy ears issued at birth were perfectly fine with us. We never intended to show the dog. We just wanted him to protect our damn tomatoes.

Sorry, said they, the ears are already done. We cannot sell a dog that does not conform to the breed standard.

I haven’t talked much about this publicly, but during this period my doctors gave me a troubling medical

diagnosis. Luckily, the cancer was eminently treatable. But I would be shuttling daily to two different facilities for treatment. Did we really want the responsibility of a puppy as I endured chemo-radiation? Should we forfeit our deposit and walk away?

We couldn’t abandon this face.

When I was sick and wasting away, I’d wake from an unplanned nap to find the little guy asleep on my belly. When I woke mornings dreading the day, the only thing that got me out of bed was the thought that we had to walk the dog.

Months have passed, and the world looks different. I have grown accustomed to people stopping to say, “Sir, you have a very pretty dog.” (For some reason, it’s always hefty Southern gentlemen who use this phraseology.) I’m in remission, healthier, and stronger. I’ve gained back some of the forty-five pounds I lost, but constant walks and puppy training sessions have kept excess poundage at bay. I know the trails in the woods behind my house far better than I ever did before, and walk about 10 miles more a week than I ever have. My cholesterol’s dropped. Even my eyesight is better.**

Without hesitation I can say that this animal has saved my life.

Still, it’s challenging living with an 80-pound lap dog who doesn’t know his own strength. True to Herr Dobermann’s vision, the dog follows me everywhere—except when on a leash. He chases fish and tadpoles in the pond below the house, even though he’s too heavy to swim gracefully. He detests the rain, and won’t deign to walk in it. He peers curiously at passing hawks, crows, airplanes, but growls at the occasional Chinook helicopter. After each morning’s walk, he insists upon sitting perfectly erect in the front yard, head swiveling to check the perimeter of the entire neighborhood.

The groundhog under the shed is long gone. I must have missed the moving truck. Rabbits, turkeys, feral cats, and squirrels do not tarry long within our fenceline.

But since Mother Nature is a prankster, we have new problem.

The dog’s new favorite thing? Tearing up and scattering tomato plants to the four winds. Who can blame him? It’s the best fun ever.

* In Europe, kennel clubs retain two N’s when referring to the breed; in the U.S., it’s one N. The Europeans also reject the term pinscher, which means terrier, as inaccurate; Americans continue to use it.

** I know this sounds incoherent at first glance. But conditions such as ocular hypertension are apparently reduced by something called exercise. Never tried it until now.

Query: If anyone knows of dog handlers who have worked with the breed in law enforcement or military settings, kindly get in touch. I’m collecting interviews for a future nonfiction project.

See you in three weeks!

Joe

.png)