by Michael Mallory |

Paget's Original Deerstalker Illustration

|

Here’s a simple experiment: draw a stick figure, like a “Hangman” victim, and then ask anyone who it is.

They will not know. How could they?

Now cover the round circle head in a cap with a front and back brim and a bow on top, and ask again.

The reply is guaranteed to be “Sherlock Holmes.”

Once a symbol of country life, the common deerstalker──a tweed cap with ear-flaps worn by hunters in rural areas of England as they (wait for it…) stalk deer──has incongruously become synonymous with one of the most renowned Londoners of all time.

How did this turn of events come about?

Blame it on the illustrator. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle never mentioned a deerstalker by name in any of his 60 Holmes adventures, though in the 1891 short story “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” Dr. Watson described Holmes as traveling to a village in Hertfordshire wearing “a close-fitting cloth cap.” That could, of course, just as easily have signified a flat “newsboy” cap. But one year later, when “The Adventure of Silver Blaze” first appeared, Watson got a little more specific in describing Holmes’s headgear, stating he wore “his ear-flapped travelling cap” to Dartmoor. While flat caps of the era sometimes came with ear protectors, the “Silver Blaze” description certainly sounds like a deerstalker, so Strand Magazine illustrator Sidney Paget took the inference and ran with it.

Paget first depicted Sherlock Holmes wearing a deerstalker for “Boscombe Valley,” and then recreated that illustration nearly verbatim for “Silver Blaze.” As a result, the cap immediately became shorthand for the appearance of Holmes, so much so that he was rarely depicted in any stage or film incarnation without it. This was despite the fact that a deerstalker in London would have looked as out-of-place to a fashionable Victorian as would a Native American war bonnet.

|

Bernhardt in Fedora

|

A half-century after Sidney Paget’s iconic drawings of Holmes, another form of headgear started to be identified with a detective, albeit a tougher, harder-boiled one. This was the fedora, whose origins were anything but tough…or even male.

French stage star Sarah Bernhardt wore a unique hat in her starring role in a popular 1882 play by Victorien Sardou: it was a soft felt hat with a narrow brim (narrower than most women’s hats of the time, anyway), and rather lavishly decorated.

The play was called Fedora and the hat caused a sensation. Parisian women raced to their milliners to request “a Fedora hat,” which is how the name got pasted to the style. In short order the chapeau became unisex, though men’s fedoras tended to be less-showy, except for the one sported by Oscar Wilde. His signature version of the fedora, which was always worn at a dramatic angle, featured a tall, dented crown and a wide, turned-down brim.

|

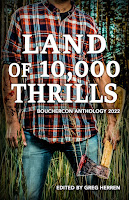

Bogart in The Big Sleep

|

By the 1920s, the fedora was well on its way to becoming the default hat for city men, edging out the derby, the more formal homburg, and the straw boater. By the ‘30s, it was hard to find a man who was not wearing a fedora, either a weather-durable felt one for autumn and winter, or a chic Panama straw fedora for spring and summer. Derbies and boaters were more commonly seen on film comedians of the era than the average man on the street.

How, then, did the fedora become de rigueur for a 20th century gumshoe──usually accompanied by a trench coat? The answer is time plus the march of fashion.

In the period between the two World Wars, fedora hats were so universal that they were not even referred to as such. One could read every novel written between 1930 and 1960, and watch every film produced within that time, and encounter the word “fedora” less than two-dozen times. The lids were referred to simply as “men’s hats” or “soft hats.” As widespread as they had been, though, by the late 1950s, classic fedoras were on the way out.

|

Andrews in Laura

|

Many blame President John F. Kennedy for this since he famously chose not to wear hats (he did carry a Cavanagh brand fedora for photo ops, though, since the head of the Cavanagh Hat Company was an old Navy friend of the president’s). But the truth is that fashion sense had been changing for some time prior to Camelot.

The porkpie hat──not the comically flat one worn by Buster Keaton, but taller ones made of felt or straw that also bore snap brims──had become prevalent. What remained of the fedora morphed into the “trilby,” a hat that was similar in shape but with a shorter, tapered crown and a much narrower brim, and sometimes made of leather.

By the end of the 1960s, most men did not wear hats at all, and those who did often preferred the more casual lids such as fishing hats, bucket hats, or “skipper” hats.

Yet the images from the movies remained. Humphrey Bogart decked out in a fedora and trench coat in The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1943), and The Big Sleep (1946), plus Dana Andrews similarly attired in Laura (1944), solidified the connection. Just as “ten-gallon” hats defined the look of the Westerner in people’s eyes (the classic “cowboy hat” being more a product of Hollywood than reality), so did the fedora and trench coat become the de facto uniform for a private eye on screen, though that connection would not really enter into the collective consciousness until a generation after the fact.

|

Eddie Constantine in Alphaville

|

As the wartime trench coat gave way to sleeker rain coat, and the classic straight-crowned, wide-brimmed fedora went the way of pocket watches and spats, what was normal daily dress evolved into a costume, one that was resurrected by later filmmakers who wanted to evoke that lost time.

French director Jean-Luc Godard revived the look in Alphaville (1965), his bizarre, futuristic homage to film noir, while Peter Sellers lampooned it as Inspector Clouseau.

And while some might argue that Indiana Jones rescued the fedora from total association with detectives, it was the kind of rescue that lasted only until the next Indy film.

|

| Downey in Sherlock Holmes |

Through no fault of their own, the humble, practical deerstalker and the once-ubiquitous fedora defined more than a century of fictional sleuths. So iconic have they become to their archetypal characters that the decision to put Robert Downey, Jr. in a Wildean fedora in Sherlock Holmes (2009) seemed somewhere between an anachronism and a sacrilege.

.jpg)