Don’t be like me. If you write short stories, read A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders now. Read it in paper, so you can scribble notes or highlight as you go. Depending on your years immersed in the craft, you will either a) learn things, or b) find fresh ways to think about the gift for creation you have so carefully nurtured.

For 20 years, Saunders, a MacArthur Fellow, has taught creative writing to MFA students at Syracuse University. His favorite class is one he teaches on 19th-century works of Russian fiction in translation. His book is a crash course on that class. We read seven short stories by four writers—Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, and Turgenev—and Saunders walks us through them. What he teaches his students, he teaches us.

Before I sprung for the book, I listened to a podcast Saunders did with Ezra Klein at the New York Times, and I was struck by the professor’s marvelous gift for conversation. I envy anyone who can speak articulately, with nuanced vocabulary, about complex topics at the drop of a hat. I cannot do that. In fact, I am certain that the reason I write is because I can’t speak well. His comments on revision, especially, about managing the writer’s “monkey mind,” are spot-on. As I read the book, I was pleased to see/hear/feel that same voice on the page. I found myself highlighting things as I read. Here are four disparate observations he makes in the first few pages of the book.

“Notice how impatient your reading mind is or, we might say, how alert it is… Like an obsessed detective, the reading mind interprets every new-arriving bit of text purely in this context, not interested in much else… One of the tacit promises of a short story, because it is so short, is that there’s no waste in it. Everything in it is there for a reason…”

***

“When I’m writing well , there’s almost no intellectual/analytical thinking going on. When I first found this method, it felt so freeing. I didn’t have to worry, didn’t have to decide, I just had to be there as I read my story fresh each time…willing to (playfully) make changes at the line level, knowing that if I was wrong, I’d get a chance to change it back on the next read.”

***

“We have to keep being pulled into a story in order for it to do anything to us…. Would a reasonable person, reading line four, get enough of a jolt to go on to line five? Why do we keep reading a story? Because we want to. Why do we want to? That’s the million-dollar question: What makes a reader keep reading? …. A story (any story, every story) makes its meaning at speed, a small structural pulse at a time. We read a bit of text and a set of expectations arises…. We could understand a story as simply a series of such expectation/resolution moments.”

***

“(A)story is a system for the transfer of energy. Energy made in the early pages gets transferred along through the story, passed from section to section, like a bucket of water headed for a fire, and the hope is that not a drop gets lost.”

I’m sure the writers among you were nodding as you read these few selections. His biggest global observation or piece of advice is what I call the Big Duh: stories are about escalation. Three times in the book he offers his rule: “Always Be Escalating.”

Professional writers practice this intuitively because they’ve learned the lesson the hard way. Young writers don’t. When Saunders reads student work, his eyeballs smack into expositions that drag on forever. The writers are talented young people, or else they wouldn’t be in this program, but at this stage in their careers, good writing means pretty sentences. They bog down in a recitation of opening splendors.

|

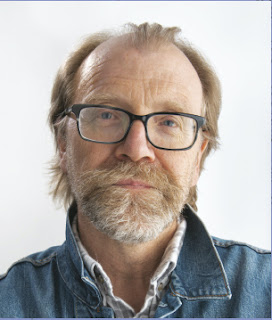

| Saunders. (courtesy Penguin Random House) |

This is nothing new. When Saunders was a student at the same institution, his professor—Douglas Unger—compelled everyone to stop and tell a damn story, verbally, as if around a campfire. If you do it that way, human instinct takes over. Your story cannot help but have a beginning, middle, and end. The story may not be great, but it will be real. That instinct falls to pieces when you attempt to put it down on paper. Which is why you must keep writing.

When revising, Saunders says, you’re engaging in a useful charade. You make minuscule changes along the way, all the while pretending that you’re reading the piece for the first time. Why do you make this change or that one? You probably don’t know. Instinct guides your hand. If you’ve done this countless times before, you will make the story incrementally better, and you will naturally know when to stop. Some piece of you knows that if you press on, you’ll blow it.

The last short story in the book is “Alyosha the Pot,” by Tolstoy. Only after we’ve discussed it at length does Saunders reveal that Tolstoy himself was not pleased with the piece, and never returned to it after that first pass. Saunders nails the problem: the ending is ambiguous, and thus unsatisfying.

I thought Saunders would stop there. Class dismissed! But no—he shows us how the ending has been rendered in English by several translators. Then he asks some Russian friends how they would interpret the passage. Looking over his shoulder as he conducts this analysis, I could not help admire the man’s patience and dedication. It has been a long time since I’ve scrutinized a story that way. Typically, if the story works for me, great. If not, I shrug and move on. But as a writer, it’s enormously helpful to know how subtle changes alter one’s perception of a piece. To think about the problem correctly, you must put yourself in that imaginary state of Never Having Read This Before.

I heard the SFF writer Mary Robinette Kowal once remark on the podcast Writing Excuses that genre writers really ought to be reading some literary fiction, if only to understand how ambiguity can make, break, or enhance your writing. Her remark has stuck with me for years, but I didn’t fully appreciate why until I read Saunders’ skillful treatment of the topic.

This book now occupies a spot on a shelf of writing books that mean something to me. The next time I feel the urge to don my ushanka and pour a shot of vodka, it will be waiting. Thank you, Professor Saunders. Za zdorov’ye!

***

To explore further:

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life by George Saunders (432 pages, Penguin Random House, 2021)

LA Review of Books: Convo with Saunders

New York Times: Review of the book

New York Times: Transcript of the Klein/Saunders interview. (Search for “monkey mind” if you want to read a small snippet.)

See you in three weeks!

Joe

When revising, Saunders says, you’re engaging in a useful charade. You make minuscule changes along the way, all the while pretending that you’re reading the piece for the first time. Why do you make this change or that one? You probably don’t know. Instinct guides your hand. If you’ve done this countless times before, you will make the story incrementally better, and you will naturally know when to stop. Some piece of you knows that if you press on, you’ll blow it.

The last short story in the book is “Alyosha the Pot,” by Tolstoy. Only after we’ve discussed it at length does Saunders reveal that Tolstoy himself was not pleased with the piece, and never returned to it after that first pass. Saunders nails the problem: the ending is ambiguous, and thus unsatisfying.

I thought Saunders would stop there. Class dismissed! But no—he shows us how the ending has been rendered in English by several translators. Then he asks some Russian friends how they would interpret the passage. Looking over his shoulder as he conducts this analysis, I could not help admire the man’s patience and dedication. It has been a long time since I’ve scrutinized a story that way. Typically, if the story works for me, great. If not, I shrug and move on. But as a writer, it’s enormously helpful to know how subtle changes alter one’s perception of a piece. To think about the problem correctly, you must put yourself in that imaginary state of Never Having Read This Before.

I heard the SFF writer Mary Robinette Kowal once remark on the podcast Writing Excuses that genre writers really ought to be reading some literary fiction, if only to understand how ambiguity can make, break, or enhance your writing. Her remark has stuck with me for years, but I didn’t fully appreciate why until I read Saunders’ skillful treatment of the topic.

This book now occupies a spot on a shelf of writing books that mean something to me. The next time I feel the urge to don my ushanka and pour a shot of vodka, it will be waiting. Thank you, Professor Saunders. Za zdorov’ye!

***

To explore further:

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life by George Saunders (432 pages, Penguin Random House, 2021)

LA Review of Books: Convo with Saunders

New York Times: Review of the book

New York Times: Transcript of the Klein/Saunders interview. (Search for “monkey mind” if you want to read a small snippet.)

See you in three weeks!

Joe

hey folks, the software has apparently decided to make it hard to comment today. We aren't picking on you.

ReplyDeleteI'm ordering this one, Joe. Thanks for telling us about it!

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you liked it! Hope you enjoy the book.

DeleteGreat post! I wish I could've been in his class. These days I find myself rereading and editing my stories far more often and more boldly than I once did. Every sentence counts.

ReplyDeleteI'm guessing that the real message of his instruction hits you best when you have a number of years of writing under your belt. I don't think I was as receptive as a young creative writing student as I would be today.

DeleteI read Saunders' book as soon after it came out and so much enjoyed and admired, for so many of the reasons you mentioned. (It also made me feel like I'm not hardly as strong a teacher as I should be. Saunders is brilliant and curious and inspiring.) I'm actually going to write about the book myself in a short piece ahead for EQMM's blog—since one chapter particularly inspired and guided my own story for the next issue. Stay tuned, and thanks for the great post here.

ReplyDeleteI look forward to see what you write. I could talk about this book forever.

Delete