Conventional wisdom says that books are sold on the basis of word of mouth. This rule of thumb is usually interpreted to mean the spoken word. Your friend tells you about a book that they loved, and you rush out to get it, or at least put it on your to-be-read list. A harried buyer dashes into a bookstore looking for a “good book” that they can take on a beach vacation, and a quick-thinking bookseller presses a book into their hands that does not disappoint. Good booksellers are part-clairvoyant, part-psychologist, but I digress.

Sometimes the sale happens exactly the way that the book industry wishes it would. A prominent critic writes a glowing review in a major newspaper—and people buy it on the strength of those few words alone. There’s even a school of thought that says reviewers must carefully choose the right buzzwords that will tell readers if the reviewed content is right for them. After all, even if the reviewer hates the book or movie, the reader might perceive it to be their cup of tea, if the review is crafted correctly.

In 1988, I was that mark. I read a review in the New York Times then bought the book, even though it was still only available in hardcover. I was 23 years old, working a crappy editorial job out of college, and I didn’t buy many hardcovers. I was all about paperbacks back then, mostly used. But there was something about that review that made the book sound irresistible. For some reason I cannot explain, it’s the only review of a book that has stuck in my mind. The reviewer happened to mention that he liked a specific quality of the author’s skill set. It was only last week that I tracked down the review to nail down the paragraph that spurred me. Here it is:

“[Mr. Harris] knows about strange things, like the life cycle of lepidoptera, the legal spacing of fishhooks on a trotline, moths that live only on the tears of large land animals, and the amount of brain matter it takes to tan a hide. The scene where Clarice Starling explores Dr. Lecter’s tip by forcing her way into a storeroom and investigating the back seat of a vintage Packard is a tour de force of descriptive economy.”

The book, of course, is The Silence of the Lambs, by Thomas Harris, which was published 34 years ago this month. (I assure you that I too am appalled by the passage of time.) The book spawned an Academy Award winning movie, and a media franchise that has included four books, five films, a TV series, and, horrors, a musical.

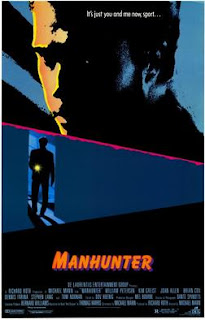

I don’t consider myself to be a Hannibal Lecter fan. Nor am I a Thomas Harris fan. Nor do I actively seek out serial killer fare. Cannibals? Yuck. I believe Silence just hit me at a formative time in my career, and I proceeded to read Harris’ first two thrillers, Black Sunday, about a terrorist plot to detonate a bomb at a Super Bowl game, and Red Dragon, the first novel to introduce Lecter. Dragon was made into a 1986 movie by Michael Mann, called Manhunter, which went straight to VHS.

Lately, I’ve been trying to understand why I like the books and media that I like. Is it the writing? The plot devices? What the hell was I hoping to glean from an author who “knows about strange things”? Why did I bring a notebook to the theater on my second viewing of Silence and take copious notes on its structure?

Well, besides the fact that I’m a kook, I think there are some boxes in my crime fiction interests that those early books and movies ticked.

I’m a sucker for psychological elicitation scenes, where a brilliant (or insane) shrink gets at the heart of the protag’s issues with a couple of quick questions. The Lecter/Starling relationship, which was hinted at in Christopher Lehman-Haupt’s Times review probably hooked me. Besides analyzing Starling, Lecter nutures her career, asking questions that prompt her to crack the case: “How do we begin to covet, Clarice?” Foster and Hopkins make the movie, but their onscreen time together amounts to a mere four scenes. If I dig deeper into my mystery fiction background, I was probably cued to enjoy shrink scenes from my early reading (and re-reading) of Ellery Queen novels, particularly Cat of Many Tails.

|

Cover of the first edition. |

I’m a sucker for the hurting/wounded protagonist who is still remarkably competent. Starling and Will Graham, the Red Dragon protagonist, both fit the bill. Jonathan Demme, the director of Silence, said in interviews that he went out of his way to portray the FBI as competent. Graham’s problem-solving thought process, as portrayed in both the book and film, is fascinating. I still get chills when the Manhunter Graham announces ruefully that he must visit Lecter in prison to “recover the mindset.”

I don’t want to gloss over the franchise’s issues. More than any other author, Harris put serial killers on the map, for better or for worse. I’d argue the reason so many crime writers don’t want to do serial killer POVs is because Harris’s imitators did ’em worse. I too don’t care for those kinds of books, although I did enjoy an early Tony Hillerman novel that brought us inside the mind of a hired assassin, making the guy seem poignant. Silence caught flak for its homophobic/transphobic content, and the later Hannibal books are just…well, don’t get me started.

That all said, I did really admire Harris’s writing in those early books. It’s clear that he is a reporter-turn-novelist, like Michael Connelly, and a lifetime of shoe-leather research ends up on the page. He really did interview FBI profilers, visit their offices, and meet trainees at Quantico. One scene I draw inspiration from is the very opening of Red Dragon.

Will Graham sat Crawford down at a picnic table between the house and the ocean and gave him a glass of iced tea.

Jack Crawford looked at the pleasant old house, salt-silvered wood in the clear light. “I should have caught you in Marathon when you got off work,” he said. “You don’t want to talk about it here.”

“I don’t want to talk about it anywhere, Jack. You’ve got to talk about it, so let’s have it. Just don’t get out any pictures. If you brought pictures, leave them in the briefcase—Molly and Willy will be back soon.”

The “descriptive economy” that Lehman-Haupt praised in that old review is clear. One sentence and we know where the scene is taking place. By the third graf we know that we’re in the presence of two men with a history. We sense Will’s reluctance to return to the work of profiling; his regard for his family is urgent, palpable. The single, mysterious word “it” says what the two men don’t say. It is the horrific darkness at the center of the novel. All told, a simply wonderful scene that I reread from time to time, just to recover the mindset.

* * *

See you in three weeks!

Joe

Interesting column, Joe--I enjoyed this. There's so much to that book, and movie too. I remember buying the novel when it first came out, without knowing a thing about it, and loved it from the start. (I'd met Harris once, at--believe it or not--a writers' conference here in Jackson, Mississippi.)

ReplyDeleteI also remember reading in one of the early reviews of the book that it would one day be revered as an example of How to write the perfect novel. I don't know if I'd call it perfect, but I thought it was outstanding, and is still one of the only books I can think of (Lonesome Dove, The Godfather, and To Kill a Mockingbird are others) that spawned movies that were every bit as good as the novels.

Thanks for yet another great post.

Thanks for the comments, John. I have had reason to go back and look at Red Dragon more carefully over the years. His background in newspaper journalism in particular and familiarity with FBI practices is masterful. I appreciate them more and more. The ending of Red Dragon is famous for the Shiloh reference that fans debate to this day.

DeleteMy brother drew my attention to Manhunter and Red Dragon. He said at the time both were underrated. He was right.

ReplyDeleteIt's been a while since I've purchased a hardback, but I distinctly remember tracking Bob McCammon's Boy's Life and buying three hardcover versions for my brothers. I'm not sure they ever read them!

I think the thing most haters miss is that the deaths in those early two books are treated seriously, as the tragedies they are. They aren't sensationalized. Investigators have to talk about their work, and these men and women do. They're professionals. It's just that their profession forces them into dark areas. That said, I like McCammon's work, so I might check out that book as well. That's for the comments.

DeleteGreat post as always, Joe—love the mix of review and analysis and reflection. And wow, yes, where does the time go?

ReplyDeleteThank you, Art. Means a lot coming from you.

ReplyDelete