Lately I've been giving a lot of thought to the notion of being "perfectly imperfect" when it comes to writing. A psychological term intended to help people embrace the notion that perfection is a worthy goal but an unrealistic destination, attaining the "perfectly imperfect" strikes me as the best of sort of goal for writers attempting to write realistic fiction.

One of the most beloved of the tricks in any stand-up comedian's bag is the so-called "call-back." It's that move where the comedian signals the end of his set with a joke referencing a bit on which he'd earlier elaborated at some length.

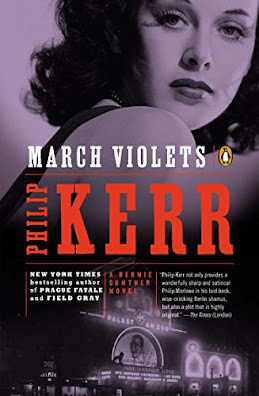

One masterful extension of this particular literary form came from the late, great Philip Kerr. In March Violets, the opening book in his unforgettable series featuring Weimar/Early Nazi era Berlin P.I. and former homicide cop Bernie Gunther, Kerr introduces his protagonist to Inge Lorenz, an attractive lady muckraker journalist. The two join forces both professionally and romantically, and the lady reporter proves a welcome resource in Gunther's ongoing search for the stolen necklace of the daughter of a wealthy industrialist.

At one point Gunther leaves Inge waiting in the middle of a suburban Berlin street while he investigates the house of one of the leads in their case. When he comes back just a few minutes later, the street is empty. No sign of Inge.

Gunther looks for Inge, but to no avail. She has simply disappeared without a trace. The case moves on to its inevitable conclusion. The book ends with the case solved, but Gunther never having found out what happened to Inge.

It's a loose end. And a pretty sizable one.

I learned early on in my crime fiction apprenticeship about the importance of the notion of "fair play with the reader," including, at least implicitly, the tying up of any and all loose ends. This is an unofficial rule of crime writing that goes back at least as far as Agatha Christie.

This "rule" arose in crime fiction writing largely in response to writers who employed all sorts of cheap maneuvers to cover for weak plots and lazy writing: you know, the detective reveals the killer and it turns out to be someone never mentioned, or even hinted at, up to this point in the novel, etc. Cheap bailouts of this type were not to be tolerated in a world where the Fair Play rule in effect.

And yet, is this sort of thing "realistic"?

Of course not. Life is messy. And while "real" and "realistic" are and never ought to be considered the same thing, realism requires at least the imitation of the rhythms and shades, lingua franca and cultural idioms of real life.

|

| The Master |

And for his next trick, Kerr goes on to "unsubvert" the Fair Play rule. Without giving too much away, Gunther stumbles across evidence of Inge's fate in a later novel. The description of what happened to her is not only believable, but also provides Gunther incentive to take down a couple of nasty customers he is investigating at the time: a full year after Inge's disappearance.

Fair Play delayed for the sake of literary realism, and eventually achieved in a completely realistic way.

Further proof supporting my long-held belief that to read the likes of Philip Kerr is to take a master class in plotting, conflict and character development.

And how's that for being "Perfectly Imperfect"?

|

| And yes, this IS my example of a "callback." |

In the day and age of the unreliable narrator (a trope of which I personally am not a fan), do loose ends left unexplained help or hinder the narrative? If so, how many are too many?

I look forward to reading your thoughts in the comments.

See you in two weeks!

I am also fed up with unreliable narrators, whether because of drink/drugs or dementia. Professional liars are fine with me, because there's a lot of them around.

ReplyDeleteMeanwhile I don't mind loose ends if they make sense, as in life - after all, we never find out what happened to Lara in "Doctor Zhivago." That's one hell of a loose end. Nor what happened to Zhivago's wife and children. Kerr's loose end with Inge makes perfect sense in pre-war Nazi Berlin.

In the context of a series, loose ends usually indicate to me that the issue will be addressed in a later novel. Sometimes, the author will hint that the issue is being left for the future.

ReplyDeleteIn a stand alone story, I have a problem with loose ends if they don't fit the context of the setting. Not knowing exactly what happened to people during WWII or the Russian Revolution or during various other wars/revolutions makes sense. Helplessness to resolve disappearances and lack of closure are hallmarks of these situations and settings.

However, if we are talking about a plot thread simply dropped and forgotten, never to be mentioned again, in a locked room mystery or cozy that's a problem for me.

I'd just mentioned Philip Kerr yesterday!

ReplyDeleteA sci-fi writer, perhaps Samuel R Delany, used to leave unfired guns on his walls all the time. I eventually grew used to it, but even as a reader and not yet a writer, I knew something wasn't right.

I'm glad Kerr revealed Inge's probable fate.

My mother used to say if something was worth doing, it was worth doing right. The counter-argument is if it's worth doing, it's worth doing wrong (rather than not doing it at all).