|

| The Folklorist and the Librarian |

I assume that last month you, like the rest of the world, heard that rapper Nicki Minaj told her millions of followers that her Trinidadian cousin refused to get the covid vaccine because his friend got it and his testicles swelled up.

I know nothing about Nicki Minaj and less about virology, but my instant reaction was: "I recognize a FOAF when I hear about one." And that brings up a subject I have been meaning to write about for years: urban legends.

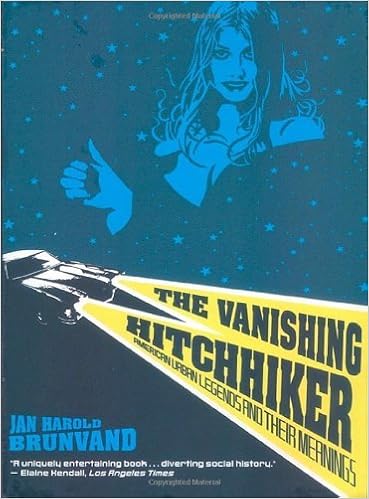

I first learned about them

when I read Jan Harold Brunvand's book The Vanishing Hitchhiker. Dr.

Brunvand is a folklorist and he did not invent the study of urban

legends but he popularized it in a series of books, starting with TVH. (By the way, I corresponded with Dr. B. in the early days of email and even coaxed him into speaking at my university.)

"Urban legends" are so named to distinguish them from standard folklore which is assumed to be the product of rural regions and allegedly unsophisticated people. Like their country cousins, urban legends are told by people who believe them to be true, and often swear that they know people who know the person they happened to (the Friend of a Friend, or FOAF). The stories often reflect whatever issues are running through the zeitgeist, and frequently have a moral, usually in the form of a warning.

An urban legend is a classic example of a story a reporter may consider "too good to check" but Brunvand pointed out at least one example of a reporter eagerly trying to find the origin of a tale -- only to see it constantly receding like the horizon. After realizing there was no truth to it, he kept following from source to source, just to see how far back it would go. Of course, he could not identify its beginning.

Let's take an example: the "Choking Doberman." This version appeared in Woman's World magazine in 1982, as part of an article called "Rumor Madness":

A weird thing happened to a woman at work. She got home one afternoon and her German shepherd was in convulsions. So she rushed the dog to the vet, then raced home to get ready for a date. As she got back in the door her phone rang. It was the vet, telling her that two human fingers had been lodged in her dog's throat. The police arrived and they all followed a bloody trail to her bedroom closet, where a young burglar huddled -- moaning over his missing thumb and forefinger.

This legend had appeared in various newspapers a year earlier with reporters contacting local authorities in search of the truth, to no avail of course. ("Police can't put finger on story.") An interesting fact is that as the story mutates the burglar's digits often become "black" or "Mexican" fingers. As I said, you can learn a lot about American obsessions by watching legends grow.

By the way, years later I read a short story in a mystery magazine which ended with the dog owner getting a call from the vet urging him to "Leave the apartment now!" but the bloody burglar is already coming toward him, seeking revenge.

Brunvand also tells about the "Attempted Abduction," in which a child disappears while shopping with her mother in a department store. Two women are caught in the bathroom, having cut and dyed the child's hair and changed her clothes. The moral is clear: Keep a close eye on your kids!

Of course, the story is highly unlikely. One attorney: "How could you dye a kid's hair in a public restroom? I'd rather give a cat a bath." And reporters were (surprise!) unable to trace the source of a story in which the location, store name, and gender of the child kept shifting with each telling.

Brunvand noted that the story seemed to appear every five years, but it actually popped up again three years after he reported it. And the next year it showed up in Ann Landers' column.

As far as I can tell the good professor stopped writing his books before social media came along, much less "alternative facts." I'm sure folklorists are keeping busy following the latest versions.

I suspect that the researcher would be overwhelmed by the all the myths and rumors of the web. But maybe there's a good short story in one of these tales?

ReplyDeleteI've certainly read stories based on some of these legends.

DeleteA FOAF took the Covid vaccine and two days later his neighbor's doberman was dead, having choked on his swollen testicles. Or something like that. Anyway, I swear the story is true beause it happened in (I think) Puerto Rico.

ReplyDeleteI hate when that happens.

DeleteI love this kind of thing. I have often used "The Choking Doberman" and stories like "The Hook" (remember that one?--I first heard it in high school) in my short-story classes as examples of mini-stories where the plot is everything and the characters are only there to hold the story together. I had not heard the one about the child and the dyed hair!

ReplyDeleteJohn, you got me thinking. A story in which plot is everything and the characters don't matter: that's a parable. And parables, like urban legends, often have a moral. Interesting. Oh, and the title of Chapter 3 of The Vanishing Hitchhiker is "The Hook and Other Horror Stories."

DeleteI worked in a store in the 1980s where we caught a guy putting hair color on a kid that had gotten separated from his Mom. He had duct taped the little boy's hands together and his mouth. Several of us fought him and kept him in the store until police arrived and took control. He had been missing for about ten minutes when we started looking for him. We later found out the dude was a multi convicted sex offender out on parole. He got violated back to Huntsville.

ReplyDeleteAs the lawyer said, not easy to do successfully.

DeleteAh, yes - urban legends. The squirrel that comes up the toilet when it flushes, biting the sitter you know where, so always flush AFTER you get up! The person who goes on a wild date and gets blind drunk and wakes up in the morning in the bathtub, packed in ice, with a note taped to the telephone "Thanks for the kidney, better call 911 right away."

ReplyDeleteA jug of wine, a FOAF of bread, and thee… sitting under the yum-yum-tree.

ReplyDeleteSome seem programmed for this. A journalist took it upon himself (or herself) to follow up those click-bait pieces, those like "The One Food to Never Eat" or "The One Medical Procedure That Can Kill You'. She (or he) clicked for hours and days, and encountered many, many ads, but never reached the article itself.