by Robert Lopresti

by Robert LoprestiOur recent extravaganza about families got me thinking about a related subject. I didn't have time to write about it during our special fortnight because I was working on another project, one I will write about here in July. But since no one else covered this aspect of the subject I thought I would take a shot of it.

We wrote about having mystery writers in the family. But what about those families with, heaven help them, two mystery writers in the family? Here are the ones I could think of. Please tell me who I missed.

Married Couples

Ross Macdonald and Margaret Millar. Kenneth Millar married Margaret Sturm when they were both in their early twenties. Ken published stories first but Margaret got her first novels out ahead of him. To avoid confusion he tried various pseudonyms, eventually settling on Ross Macdonald, much to the fury of John D. MacDonald who didn't accept the lower case D as a big enough difference. Ross and Margaret both were named Grand Masters by MWA, in different years. They never collaborated.

Bill Pronzini and Marcia Muller. The other MWA Grand Master couple, both still publishing. They mostly write separately but have collaborated and even had their characters work together. They have also both been awarded the Eye for lifetime achievement by the Private Eye Writers of America.

William DeAndrea and Jane Haddam. DeAndrea won Edgars in three different categories, and that doesn't happen very often. Haddam has been nominated twice for an Edgar and once for an Anthony. DeAndrea died ridiculously young in 1996; Haddam is still active.

The Gordons. Gordon and Mary Gordon wrote many novels under the name The Gordons (which must have really bugged library catalogers). Many of them featured FBI agent John Ripley, leaning on Gordon Gordon's Bureau experience during World War II. They are perhaps best remembered for Undercover Cat, which Disney filmed as That Darned Cat. In the book the word was not darned, but hey, that's Disney.

Margery Allingham and Pip Youngman Carter. Allingham was, of course, the very successful creator of crime novels about Albert Campion. Hubby Carter was an artist who created her book covers, and wrote about thirty crime short stories of his own. When his wife died Carter finished her last book, Cargo of Eagles, and then wrote two more Campion books on his own.

Dick Francis and Mary Francis. Put a question mark by this one. Dick Francis was the only name on the cover of those books, although he acknowledged his wife as his researcher and editor. (She also took the photographs that graced the covers of the British editions of his books.) Late in life he said "She was in a way a co-author, but she wouldn't take the credit. I don;t really know why. She didn't really like publicity, and she was quite happy for me to have all the credit." Eventually some people declared that Mary had actually written the books, since an uneducated jockey could not possibly have produced such brilliant books. Ironically, that was precisely the sort of snobbery Francis's protagonists were constantly subjected to. But see below.

J.J. Cook. Jim and Joyce Lavene wrote cozies under this name as well as Ellie Grant, and Elyssa Henry.

Sisters

Perri O'Shaunessy. Pam and Mary O'Shaunessy write about attorney Nina Reilly. Pam was a lawyer herself until she gave it up for literature. They have written more than a dozen novels about Reilly, plus some stand-alones.

P.J. Parrish. Kris Montee and Kelly Nichols write under this name. They have won an Edgar for their series about Detroit cop Louis Kincaid.

Brothers

Peter Anthony. Anthony Shaffer and Peter Shaffer were twins. Anthony wrote several mystery plays, most notably Sleuth. Peter wrote non-mystery dramas such as Equus and Amadeus, but together they wrote several mystery novels under the name Peter Anthony.

Brother and Sister

Robert Lopresti and Diane Chamberlain. I am embarrassed to admit this is the last pair I thought of. Diane's novels are generally described as women's fiction, rather than crime fiction. Nonetheless The Bay at Midnight and Pretending to Dance are both investigations of suspicious deaths, and The Secret Life of CeeCee Wilkes and Necessary Lies (my favorite) include kidnappings.

Father and Daughter

Tony Hillerman and Anne Hillerman. After Tony died Anne took over the Navajo police franchise. Song of the Lion is number three.

Father and Son

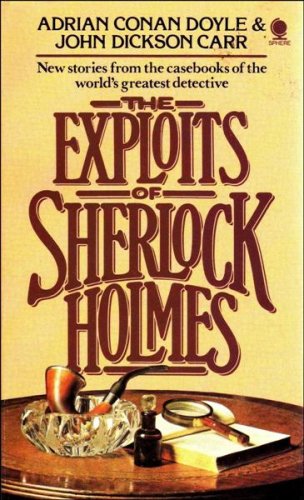

Arthur Conan Doyle and Adrian Conan Doyle. In the 1950s, decades after his father's death, Adrian teamed up with John Dickson Carr to write a series of short stories which were eventually published under the title The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes. I have always wondered whether they were aware that one meaning of "exploit" is "use selfishly for one's own ends."

Dick Francis and Felix Francis. See above. After his mother died Francis was listed as co-author of his father's books, and after Dick died, he has published several novels with titles beginning Dick Francis'...

William F. Buckley and Christopher Buckley. Among his many other books WFB wrote a series of spy novels about Boysie Oakes. His son Christopher's comic novels include No Way To Treat A First Lady, in which the protagonist is accused of murdering her philandering husband.

Mother and Daughter

Mary Higgins Clark and Carol Higgins Clark. Mary is, of course, a hugely successful author of suspense novels. Carol writes mysteries about Regan Reilly. Occasionally they write together, usually Christmas treats.

P.J. Tracy. P.J. Lambrecht, who died last year, wrote the Monkeewrench Gang novels with her daughter Traci. The gang were a bunch of computer geniuses who lived in the Twin Cities.

Mother and Son

Charles Todd. That is the pen name for Caroline and Charles Todd. Their most famous books feature Ian Rutledge, a Scotland Yard detective who is haunted by his experiences in the Great War. Specifically , he is accompanied everywhere by the voice of Hamish MacLeod, a soldier he had executed for disobedience during battle.

Cousins

Ellery Queen. You didn't think I would forget them, did you? Frederick Dannay and Manfred Lee defined the crime-writing-duo for more than four decades. Supposedly Dannay created the plots and Lee wrote the words.

I am sure I missed a bunch. Please add them in the comments.