And one that I hear really often: What, exactly, IS a mystery?

What is it indeed? Does it have to be a whodunit? Must it include a murder? Must it always feature a detective? It's one of those arguments that could be called, well, mysterious.

Criminal activity

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."NOTE: In looking over the Amazon reviews for The Best American Mystery Stories 2015, I notice that several reviewers said they didn't like it because it included stories that weren't mysteries. My response would be that they didn't read the intro. It doesn't leave much room for doubt.

Why is such a definition important? Does it even matter? I think it does. It's important because writers need to know what they've written in order to know where to submit it. If a magazine (or anthology) editor or a book publisher or agent says he or she is looking for mystery stories/novels, then you/I/we need to know what to send and what not to send. And, again, Otto's definition seems logical. I think mysteries can be whodunits, howdunits, whydunits, etc. (Much has been said at this blog recently about the TV series Columbo, and while I think all of us would classify those episodes as mysteries, none of them were whodunits. All were howcatchems.)

Consider this: If a character spends an entire story or novel trying to murder someone and is stopped just before doing it (The Day of the Jackal, maybe?) does that story or novel fall into the mystery category? Sure it does. A crime--the threat of a crime, in this case--is central to the plot. And I can think of a few mysteries aired on Alfred Hitchcock Presents that didn't even involve a crime. One example is Man From the South, featuring Steve McQueen and adapted from the short story of the same name by Roald Dahl, and another is Breakdown, starring Joseph Cotten as a paralyzed accident victim whose rescuers believe he's dead. Some of you might've seen those, and if you did you'll remember that they were more suspenseful than mysterious.

I'll take Stephen King for 100, Alex

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.

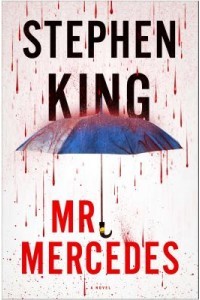

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.To get back to the subject of this column, though, I also find it interesting that King, who is of course best known for horror fiction, won a well-deserved Edgar Award last year for the novel Mr. Mercedes and another Edgar this year for his short story "Obits." Neither of them fit into some folks' idea of a mystery. The novel was more of a suspense/thriller, and "Obits" was firmly entombed in the spooky/otherwordly/paranormal category. My point is that the Edgar is awarded by Mystery Writers of America, and that in itself means those two works should be considered to be--among other things--mysteries.

Check the label

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:Eddie knew that a detective wears an

Overcoat and hat,

But he lost his pipe and magnifying

Glass, so that was that.

What Eddie didn't understand is that very few things in this life are simple and elementary, my dear Watson. Sometimes the prettiest colors are those that are blended, or at least mixed-and-matched. I think mystery is a broad category, and--IMHO--hybrids are welcome.

It's probably worth mentioning that Elmore Leonard--who was once recognized as a Grand Master by Mystery Writers of America--was always quick to point out that he'd never in his life written a traditional mystery. His stories and novels were about crime and deception, not detection. Even so, the best place to find his work is in the MYSTERY section of the bookstore.

Final Jeopardy question:

What's your take, on this particular argument? Do you think books and stories that lean more toward "suspense" or "thriller" should always be so labeled, or at least identified as a subgenre of "mystery"? Or do you agree that the inclusion of a crime qualifies any such story to be called a mystery?

Investigative minds want to know.

Great piece, John. And I think pretty much everything you describe can fall under the category of either "mystery" or "crime fiction." And I don't see why we need to have such narrow definitions of everything. I think mystery has become a catch-all for many kinds of crime fiction, whether or not there is a traditional mystery to it. And people who want to claim otherwise are spinning their wheels to no good effect.

ReplyDeleteI tend to call what I write these days "crime fiction" because there are people who think that a mystery has to be about solving who committed a crime, and a lot of what I write is from the point of view of the crime doer. That said, I'm fine with the mystery label and would be thrilled to see everything I write in a bookstore's mystery section.

ReplyDeleteI haven't read Stephen King's "Obits" yet, but I plan to. I read on a Listserv I'm on that some people thought it was a strange Edgar and winner because it didn't have a mystery in it. Ahh, those darned definitions again.

I tend to take a broad view of the genre, but I must admit that I've found more traditional forms sell better. Alas!

ReplyDeleteI agree, Paul. If there are really only five genres (romance, mystery, western, SF, and horror), then any fiction involving crime/suspense must be "mystery." Even so, there are many writers and readers who seem to feel that a piece of fiction, short or long, must be a whodunit in order to qualify.

ReplyDeleteAgain, Penzler's definition is good enough for me.

Barb, you would like the Stephen King story. In fact there are many of his in that collection (The Bazaar of Bad Dreams) that I think you'd enjoy. But yes, it probably was a strange choice for the Edgar.

Janice, I think you're right. In the case of EQMM, I'm almost certain the chances are better with a traditional mystery. AHMM seems to be more receptive to a wider range of subject matter, even to (occasionally) the inclusion of paranormal elements.

ReplyDeleteI think Otto Penzler had the right definition.

ReplyDeleteAnd John, since I've never cracked EQMM, it's interesting to get an insight into the difference between them and AHMM. Thanks for the hint!

Eve, I can't be certain about that "difference" between EQMM and AHMM (traditional vs. non-), but it does seem sometimes to be true. I am fairly sure, though, that AH is occasionally more receptive than EQ to otherworldly plots, as well as plots with a lot of humor and some other mixed-genre elements. And EQ seems to like pastiches more than AH.

ReplyDeleteLike you, I've been more successful at AHMM, but I've always loved reading 'em both.

I loved your piece, John, and I agree that "mystery" can be tough to define. Years ago, when I taught a little non-credit mystery-writing class, I defined mysteries as combining two elements, crime and the unknown. In a whodunit, the unknown element is usually something that happened in the past--the detective has to figure out who killed the victim, how the victim was killed, or something along those lines. In a thriller, the unknown element is usually something that might happen in the future--the protagonist doesn't know if the bomb will be defused in time, if the kidnapping victim will be rescued safely, and so so. Of course, many mysteries keep us guessing about both the past and the future--we wonder who killed the victim and also if the killer will strike again. It's not a terribly sophisticated definition, but I think it's inclusive enough to cover most works most people would consider mysteries.

ReplyDeleteWell said, Bonnie! I agree with the definition you gave your class.

ReplyDeleteI've always been intrigued by the differences between the elements of traditional mysteries vs. thrillers. And I still find it interesting that many traditional mysteries (whodunits?) are told in first person (or at least third-person limited) because the author doesn't want the reader to know certain things before the protagonist does (and "solves" the case), while thrillers are usually third-person multiple because the author WANTS the reader to know certain things before the protagonist does--to increase the tension and suspense we feel for the welfare of the hero. Makes sense.

I'm not a big fan of labels. But I think Penzler's definition is on the mark. Maybe that's why the British prefer to use Crime Story over Mystery.

ReplyDeleteYou're right, maybe "crime story," as Barb said earlier, would be a better term. The only glitch there is that, as mentioned in the column, some of the episodes on the old Alfred Hitchcock Presents show actually featured no crime at all. Maybe a good catch-all description would be stories of "deception," which in fact ALL of them are.

ReplyDeleteI’m still bowled over that EQMM published Swamped. It started out with a jailing but no crime and the only mystery was the stranger in the bar. But I’m grateful, oh, so grateful!

ReplyDeleteLast Thursday, I read an unusual story published in 1901, In the Fog by Richard Harding Davis, a once popular author. It employs the unreliable narrator principle with a vengeance. It’s nominally about three different takes of the same crime, but it really isn’t about that at all.

Mysteries are like what people say about art… I know what I like.

In the Fog by Richard Harding Davis can be found in several ebook formats here in Project Gutenberg.

ReplyDeleteLeigh, I'm with you: I know what I like. That's probably the best definition of all.

ReplyDeleteGreat post here, John. I've seen so many readers make those same comments on the BAMS anthologies--and about other stories and books. (In fact, I've helped judge the Edgars twice, and while I can't speak about the judging process itself, I can say that even the judges have sometimes had very clear differences of opinion about what constitutes a mystery and what doesn't. And we're the people who write them!)

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed your take on all this!

Art

Thanks, Art. Yes, that point came up a time or two when I was an Edgar judge as well. Thank goodness we were (mostly) in agreement, though. Penzler's definition does make sense.

ReplyDelete