Recently I discovered a Sherlock Holmes story, previously unknown to me, in the government documents collection of the library where I work. No, this is not one of those rare-but-real incidents of someone opening an ancient box of manuscripts and finding an unknown treasure - like this one I read about yesterday. In fact, the story I discovered was not even by Arthur Conan Doyle.

It appeared, of all places in a book published in 1980 by the Census Bureau: Reflections of America: Commemorating the Statistical Abstract Centennial. As you can probably deduce, the book was intended to celebrate the 100th edition of Statistical Abstract of the United States. If you aren't familiar with these books, they are a type of almanac of varied data, covering whatever the Census Bureau thought was most important about life in the United States that year.

Just for kicks, here are some of the tables in Statistical Abstract, and the first year they appeared. It gives you some idea when the public - or at least the government - got particularly interested in a topic.

Immigrants of each nationality. 1878.

Public schools in the U.S. 1879.

Vessels wrecked. 1885.

Area of Indian Reservations. 1888.

Telephones, number of. 1889.

Civil Service, number of positions. 1910.

Homicides in selected cities. 1922.

Accidents and fatalities, aircraft. 1944/5.

Population using fluoridated water. 1965.

Motor Vehicle Safety Defect Recalls. 1978.

Firearm mortality among children, youth, and young adults. 1992.

Student use of computers. 1995.

Internet publishing and broadcasting. 2008.

Reflections of America features essays by distinguished authors discussing many different aspects of Statistical Abstract: Daniel Patrick Moynihan, James Michener, John Kenneth Galbraith,and Jeane Kirkpatrick, to name a few.

Reflections of America features essays by distinguished authors discussing many different aspects of Statistical Abstract: Daniel Patrick Moynihan, James Michener, John Kenneth Galbraith,and Jeane Kirkpatrick, to name a few.The essay on international trade, cleverly titled "A Case of International Trade," was written by business journalist J.A. Livingston,. It begins as you see on the right over there.

It goes on for many pages. You can read it all here if you wish. But what I am pondering is: why would anyone think that's a good idea?

I'm not talking about parodies, or what I call fan fiction (creating a new case for your favorite detective). I understand those impulses. But I think it is a bit weird to use a character for a completely different purpose than what made that character famous.

So, for instance, here are a few books about (or "about") Sherlock Holmes:

The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes

Conned Again, Watson!: Cautionary Tales of Logic, Maths and Probability

What other fictional characters have become cats's paws for authors who wanted to teach a subject painlessly? I knew without looking that one young lady must be on the list and sure enough:

Alice in Quantumland

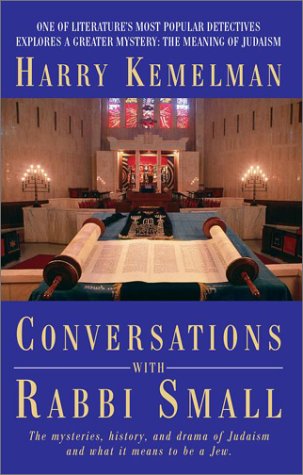

I even thought of one book in which the author himself did this to his character. Harry Kemelman's Conversations With Rabbi Small is an introduction to Judaism thinly disguised as a non-mystery novel about the amateur sleuth.

I even thought of one book in which the author himself did this to his character. Harry Kemelman's Conversations With Rabbi Small is an introduction to Judaism thinly disguised as a non-mystery novel about the amateur sleuth.I still say the instinct to do this is an odd one.

And as long as we are tying government publications to mysteries, let me point out an old federal document that is not available for free on the web: The Battle of the Aleutians: A Graphic History 1942-1943.

What's the mystery connection? It was co-authored by a rather

superannuated corporal who served in that frozen wilderness: Dashiell

Hammett.

And as long as we are tying government publications to mysteries, let me point out an old federal document that is not available for free on the web: The Battle of the Aleutians: A Graphic History 1942-1943.

What's the mystery connection? It was co-authored by a rather

superannuated corporal who served in that frozen wilderness: Dashiell

Hammett.

Clearly it is a mixed blessing to create a character so charismatic that he or she escapes not only their original books but the whole genre.

ReplyDeleteReflections on America sounds like a font of inspiration for any writer!

Given my dim view of bad pastiches (and awful Robert Downey Jr movie adaptations), I find the use of Holmes in this case rather charming. Why? First, because it’s done by amateur who obviously loves and knows the canon. Secondly, it’s not badly written at all. But there’s a third critical element. I’ll explain.

ReplyDeleteWhen I designed software, after I finished a project I had to explain what the software package did. Rather than the usual dry introduction, I led off with a humorous story (which wasn’t as well written as the Holmes pastiche example). As an independent developer, I had a lot of freedom to do things my way, but I got a lot of corporate push-back from the sales offices… they wanted the usual bland, dry-as-dust biz-speak writeup. Creativity wasn’t something to be tolerated, let alone encouraged, but I fought back and got my way. Those terrible little stories became kind of a trademark.

As tough as it was eking out creativity in the corporate world, I expect it might be harder yet in the government realm. I picture a long-ago clerk with his eyeshade, his typewriter and a bottle of white-out, plinking out that story, daring to defy the higher-ups who wanted the usual, non-committal blather. Hurray, I say!

As for the science mysteries of Sherlock Holmes, when I was a kid I loved comics or stories that reduced the tedium in history, geography, and yes, even science. I recall Superman as well as Pooh explaining some arcane topic, so why not Sherlock? It's all about relating with the audience.

I believe I’ve read Alice in Quantumland, although I don’t recall specifics. But if you’re into physics, the surreality of Alice makes a good fit– interdimensions, string theory, entanglement– the world around us is far stranger than we can imagine.

Thanks for bring the topic to our attention, Rob. Very cool article.

I read the Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes when I was a kid and loved them. And, while I never read "Alice in Quantumland", I have read and own "Alice in Puzzleland" one of the many [fiendish] logic puzzle books by Robert Smullyan. (ALL ARE EXCELLENT. And, as I said, fiendish.)

ReplyDeleteI prefer these kinds of things to the "remakes" of beloved characters, where they're revamped into something they never were - such as the Robert Downey, Jr. version of Holmes. Or the Geraldine McEwan version of "Miss Marple" who suddenly had had an affair as a young girl, etc....

As a non-writer, I'd be interested in what you all think about the spate of new "werewolf-vampire" novels using established characters and books from the 1800s. I haven't read them (or seen the movies they are apparently making now, based on those books), but . . . well, I guess what I think isn't the point. How do they strike you all?

ReplyDeleteI’m not sure about werewolves, but vampire and monster stories trace their origins back to Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley. Amazing horror writers like Oliver Onions, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and H.P. Lovecraft teased, taunted, and tantalized us in the 1800s and early 1900s. With little doubt, tales of terror and horror date back to our ancient ancestors sitting around the dying embers of their cookfires, telling stories to frighten their audience. Much of modern day writing pales in comparison, although movies tended to be rich in detail.

ReplyDeleteBut of course the real monsters aren’t Frankensteins or werewolves or vampires. They are ourselves.