So, about my day gig.

I teach ancient history to eighth graders.

And like I tell them all the time, when I say, "Ancient history," I'm not talking about the 1990s.

For thirteen/fourteen year-olds, mired hopelessly in the present by a

relentless combination of societal trends and biochemistry, there's not

much discernible difference between the two eras.

It's a great job. But even great jobs have their stressors.

Like being assigned chaperone duty during the end-of-the-year dance.

Maybe you're familiar with what currently passes for "popular music"

among fourteen year-olds these days. I gotta say, I don't much care for

it. Then again, I'm fifty-one. And I can't imagine that most fifty-one

year-olds in 1979 much cared for the stuff that I was listening to then.

And it's not as if I'm saying *I* had great taste in music as a

fourteen year-old. If I were trying to make myself look good I'd try to

sell you some line about how I only listened to jazz if it was Billie

Holiday or Miles Davis, and thought the Police were smokin' and of

course I bought Dire Straits' immortal "Makin' Movies" album, as well

Zeppelin's "In Through The Out Door" when they both came out that year.

Well. No.

In 1979 I owned a Village People vinyl album ("Go West," with "YMCA" on

it), and a number of Elvis Presley albums and 8-track tapes. I also

listened to my dad's Eagles albums quite a bit. An uncle bought

Supertramp's "Breakfast in America" for me, and I was hooked on a

neighbor's copy of "Freedom at Point Zero" by Jefferson Starship, but

really only because of the slammin' guitar solo Craig Chaquico played on

its only hit single: "Jane." And I listened to a lot of yacht rock on

the radio. I didn't know it was "yacht rock" back then. Would it have

mattered?

But bear in mind we didn't have streaming music back then. And my allowance I spent mostly on comic books.

Ah, youth.

Anyway, my point is that someone my age back then may very well have

cringed hard and long and as deeply if forced to listen to what *I* was

listening to at eardrum-bursting decibels, and for the better part of

two hours.

That was me on the second-to-the-last-day of school a week or so back.

Two hours.

Two hours of rapper after rapper (if it's not Eminem, Tupac,

or the Beastie Boys, I must confess it all sounds the same to me)

alternating with "singing" by Rihanna, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, etc.

Thank God we got some relief in the form of the occasional Bruno Mars song. Bruno, he brings it.

And through it all, the kids were out there on the floor. Mostly girls, and mostly dancing with each other.

One group of these kids in particular caught my attention. Three

girls, all fourteen, all of whom I knew. All wearing what '80s pop-rock

band Mr. Mister once referred to as the "Uniform of Youth."

Of course,

the uniform continues to change, just as youth itself does.

But

in embracing that change, does youth itself actually change? Bear with

me while I quote someone a whole lot smarter than I on the matter:

"Kids today love luxury. They have terrible manners, contempt for

authority; they show disrespect for elders and love to gab instead of

getting off their butts and moving around."

The guy quoted (in translation) was Socrates, quoted by his pupil Plato, 2,400 years ago.

And some things never change.

Getting back to the three girls mentioned above, their "uniform of

youth" was the one au courant in malls and school courtyards across the

length and breadth of this country: too-tight jeans, short-sleeved or

sleeveless t-shirts, tennis-shoes. They looked a whole lot like so many

other girls their age, out there shaking it in ways that mothers the

world over would not approve of.

In other words, they looked like

thousands, hell, millions of American girls out there running around

today, listening to watered down pablum foisted on them by a rapacious,

corporate-bottom-line-dominated music industry as "good music", for

which they pay entirely too much of their loving parents' money, and to

which they will constantly shake way too much of what Nature gave

them–even under the vigilant eyes of long-suffering school staff

members.

Yep, American girls. From the soles of their sneakers to the hijabs covering their hair.

Oh, right. Did I mention that these girls were Muslims? Well, they are.

One from Afghanistan. One from Turkmenistan, and one from Sudan. At

least two of them are political refugees.

You see, I teach in one

of the most diverse school districts in the nation. One of the main

reasons for this ethnic diversity is that there is a refugee center in

my district. The center helps acclimate newcomers to the United States

and then assists in resettling them; some in my district, some across

the country.

So in this campaign season, when I hear some

orange-skinned buffoon talking trash about Muslims, stirring up some of

my fellow Americans with talk of the dangerous "foreign" *other*, it

rarely squares with the reality I've witnessed first-hand getting to

know Muslim families and the children they have sent to my school to get

an education: something the kids tend to take for granted (because, you

know, they're kids, and hey, kids don't change). Something for which

their parents have sacrificed in ways that I, a native-born American

descendant of a myriad of immigrant families, can scarcely imagine.

(And it ought to go without saying that this truth holds for the

countless *Latino* families I've known over the years as well.)

I'm not saying they're saints. I'm saying they're people. And they're

here out of choice. Whether we like that or whether we don't, they're

raising their kids *here*. And guess what? These kids get more American

every day. Regardless of where their birth certificate says they're

from.

Just something to think about, as we kick into the final leg of this excruciating election season.

Oh, come on. You didn't think this piece was gonna be just me grousing about kids having lousy taste in music, did ya?

(And they do, but that's really beside the point.)

Blessed Eid.

30 June 2016

29 June 2016

Sherlock Holmes by the Numbers

Recently I discovered a Sherlock Holmes story, previously unknown to me, in the government documents collection of the library where I work. No, this is not one of those rare-but-real incidents of someone opening an ancient box of manuscripts and finding an unknown treasure - like this one I read about yesterday. In fact, the story I discovered was not even by Arthur Conan Doyle.

It appeared, of all places in a book published in 1980 by the Census Bureau: Reflections of America: Commemorating the Statistical Abstract Centennial. As you can probably deduce, the book was intended to celebrate the 100th edition of Statistical Abstract of the United States. If you aren't familiar with these books, they are a type of almanac of varied data, covering whatever the Census Bureau thought was most important about life in the United States that year.

Just for kicks, here are some of the tables in Statistical Abstract, and the first year they appeared. It gives you some idea when the public - or at least the government - got particularly interested in a topic.

Immigrants of each nationality. 1878.

Public schools in the U.S. 1879.

Vessels wrecked. 1885.

Area of Indian Reservations. 1888.

Telephones, number of. 1889.

Civil Service, number of positions. 1910.

Homicides in selected cities. 1922.

Accidents and fatalities, aircraft. 1944/5.

Population using fluoridated water. 1965.

Motor Vehicle Safety Defect Recalls. 1978.

Firearm mortality among children, youth, and young adults. 1992.

Student use of computers. 1995.

Internet publishing and broadcasting. 2008.

Reflections of America features essays by distinguished authors discussing many different aspects of Statistical Abstract: Daniel Patrick Moynihan, James Michener, John Kenneth Galbraith,and Jeane Kirkpatrick, to name a few.

Reflections of America features essays by distinguished authors discussing many different aspects of Statistical Abstract: Daniel Patrick Moynihan, James Michener, John Kenneth Galbraith,and Jeane Kirkpatrick, to name a few.The essay on international trade, cleverly titled "A Case of International Trade," was written by business journalist J.A. Livingston,. It begins as you see on the right over there.

It goes on for many pages. You can read it all here if you wish. But what I am pondering is: why would anyone think that's a good idea?

I'm not talking about parodies, or what I call fan fiction (creating a new case for your favorite detective). I understand those impulses. But I think it is a bit weird to use a character for a completely different purpose than what made that character famous.

So, for instance, here are a few books about (or "about") Sherlock Holmes:

The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes

Conned Again, Watson!: Cautionary Tales of Logic, Maths and Probability

What other fictional characters have become cats's paws for authors who wanted to teach a subject painlessly? I knew without looking that one young lady must be on the list and sure enough:

Alice in Quantumland

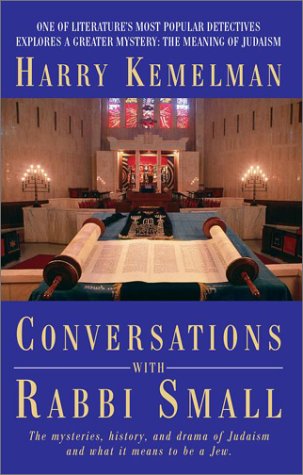

I even thought of one book in which the author himself did this to his character. Harry Kemelman's Conversations With Rabbi Small is an introduction to Judaism thinly disguised as a non-mystery novel about the amateur sleuth.

I even thought of one book in which the author himself did this to his character. Harry Kemelman's Conversations With Rabbi Small is an introduction to Judaism thinly disguised as a non-mystery novel about the amateur sleuth.I still say the instinct to do this is an odd one.

And as long as we are tying government publications to mysteries, let me point out an old federal document that is not available for free on the web: The Battle of the Aleutians: A Graphic History 1942-1943.

What's the mystery connection? It was co-authored by a rather

superannuated corporal who served in that frozen wilderness: Dashiell

Hammett.

And as long as we are tying government publications to mysteries, let me point out an old federal document that is not available for free on the web: The Battle of the Aleutians: A Graphic History 1942-1943.

What's the mystery connection? It was co-authored by a rather

superannuated corporal who served in that frozen wilderness: Dashiell

Hammett. 28 June 2016

Sometimes The Movie Is Better Than The Book – Case Study: In A Lonely Place

A classic film noir starring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame, based on a book by Dorothy B. Hughes. In a Lonely Place is one of my favorite film noirs. Hell, it’s one of my favorite movies of any genre. But there are two In a Lonely Places. The book and the movie. Some people are fans of both. Others fans of one or the other. I’m the other. I’m a much bigger fan of the movie than the book. That said, I like the book, but I don’t love it. I know a lot of Hughes fans will take what I say here as sacrilege, so get the bricks and bats ready. Uh, for those literalists out there I’m talkin’ figurative bricks and bats.

And that said, the focus of this piece is pretty narrow, dealing mostly with just one aspect of the movie vs. the book. But a major one.

There are several differences between the novel and the movie. But the main thing is that the book is a pretty straight-forward story about a psychopath who murders for fun, if not profit. In the book, he’s a novelist who sponges off his uncle…and worse. The movie (written by Andrew Solt and Edmund H. North, and directed by Nicholas Ray) is about a screenwriter with a temper and poor impulse control, to say the least. He’s a war hero. A previously successful screenwriter trying to get his mojo back, though I doubt that’s a term he would recognize.

He’s up to do a screenplay based on a book that he doesn’t want to read. So, he brings a woman home to his apartment to read the book to him. He gives her cab money when she’s done. She splits…and is murdered that night. Naturally, he’s a suspect. His alibi witness, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), just moved into his building. He’s charismatic in his own special way and after they meet at the police station, a romance buds between them. But, as the story progresses, she sees the negative sides of his personality, his rage, his jealousy, the way he treats his agent, and she begins to doubt his innocence.

In the book it’s pretty straight-forward. He’s guilty—he’s a psychopath who gets off on killing. In the

movie, we’re not sure because we haven’t actually seen him kill anyone, though we have seen him lose his temper, get into fights, and nearly kill an innocent kid. So, like Laurel, we, too, begin to doubt his innocence.

The novel is, to me, a much more straight-forward story about a serial killer and a more overt bad guy. He’s a psychopathic killer, no doubt about it. In the movie, we’re just not sure. That makes all the difference, especially in his relationship with Grahame. The movie is more ambiguous and with a more ironic ending. Because of this, in my opinion, the movie works much better and seems to strike a fuller chord. However, maybe when the book came out dealing with this psychopath it was more shocking and in turn seemed to have more depth than I see in it today.

Also, in the movie, Dix Steele is much more complex with many more layers to his personality. We like him or at least want to like him. But it’s hard, just as Laurel finds it harder and harder to like him, and especially trust him as time goes on and she sees the dark sides of his personality. We relate to Laurel’s dilemma and find ourselves going along with her and doubting Dix’s truthfulness. We start to believe he really is the killer. We judge him and convict him in our heads just like Laurel does. And we eventually realize how wrong we were as we and Laurel discover the truth.

In the end, Dix and Laurel’s relationship is destroyed by doubt, fear and distrust, even though he’s innocent, because she’s seen that other side of him. And even though Dix Steele doesn’t turn out to be the killer, this is far from a Hollywood happy ending. Very far from it.

The movie takes the basics of the book and adds an ambiguity that leads to a much more bittersweet and poignant story and ending than in the book. So this is a case where the filmmakers did change a certain essence of the story, but it works out for the better.

The movie is noir in the sense that Bogart is tripped up by his own Achilles Heel, his fatal flaw. To me, the thing that most makes something noir is not rain, not shadows, not femme fatales, not slumming with lowlifes. It’s a character who trips over their own faults: somebody who has some kind of defect, some kind of shortcoming, greed, want or desire…temper or insecurity, that leads them down a dark path, and then his or her life spins out of control because of their own weaknesses or failings. Here, Dix is innocent, but a loser, at least in a sense, and will always be a loser. His personality has driven away the one woman who really loved him. Love loses here too, as does Grahame’s character. Her inability to completely trust and believe in Dix leads to her losing what would have been the love of her life. It’s this ambivalence that make it a better movie than book, at least for me. There is, of course, much more to say about this movie, but my point in this piece is just to point out why I like the movie better than the book.

Dix and Laurel love each other, but they can’t be with each other—summed up in some famous lines from the film:

I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a

few weeks while she loved me.

Ultimately both versions need to stand on their own and they do. But for me, the bottom line is: I’d say: Good book, great movie.

As a side note, a long time ago I bought a poster of the movie from Pat DiNizio (lead singer and songwriter of the Smithereens), who did a great song based on the movie called—of all things—In a Lonely Place. The lyrics paraphrase the famous lines from the movie above. So, every time I look at the poster I think about him sitting under it, writing that song. Doubt he’d remember me, but for me that’s a cool memory. Click here to watch the YouTube music video.

And that said, the focus of this piece is pretty narrow, dealing mostly with just one aspect of the movie vs. the book. But a major one.

***SPOILERS AHEAD – DO NOT TREAD BEYOND THIS POINT IF YOU HAVEN’T SEEN THE

MOVIE OR READ THE BOOK***

There are several differences between the novel and the movie. But the main thing is that the book is a pretty straight-forward story about a psychopath who murders for fun, if not profit. In the book, he’s a novelist who sponges off his uncle…and worse. The movie (written by Andrew Solt and Edmund H. North, and directed by Nicholas Ray) is about a screenwriter with a temper and poor impulse control, to say the least. He’s a war hero. A previously successful screenwriter trying to get his mojo back, though I doubt that’s a term he would recognize.

He’s up to do a screenplay based on a book that he doesn’t want to read. So, he brings a woman home to his apartment to read the book to him. He gives her cab money when she’s done. She splits…and is murdered that night. Naturally, he’s a suspect. His alibi witness, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), just moved into his building. He’s charismatic in his own special way and after they meet at the police station, a romance buds between them. But, as the story progresses, she sees the negative sides of his personality, his rage, his jealousy, the way he treats his agent, and she begins to doubt his innocence.

In the book it’s pretty straight-forward. He’s guilty—he’s a psychopath who gets off on killing. In the

movie, we’re not sure because we haven’t actually seen him kill anyone, though we have seen him lose his temper, get into fights, and nearly kill an innocent kid. So, like Laurel, we, too, begin to doubt his innocence.

The novel is, to me, a much more straight-forward story about a serial killer and a more overt bad guy. He’s a psychopathic killer, no doubt about it. In the movie, we’re just not sure. That makes all the difference, especially in his relationship with Grahame. The movie is more ambiguous and with a more ironic ending. Because of this, in my opinion, the movie works much better and seems to strike a fuller chord. However, maybe when the book came out dealing with this psychopath it was more shocking and in turn seemed to have more depth than I see in it today.

Also, in the movie, Dix Steele is much more complex with many more layers to his personality. We like him or at least want to like him. But it’s hard, just as Laurel finds it harder and harder to like him, and especially trust him as time goes on and she sees the dark sides of his personality. We relate to Laurel’s dilemma and find ourselves going along with her and doubting Dix’s truthfulness. We start to believe he really is the killer. We judge him and convict him in our heads just like Laurel does. And we eventually realize how wrong we were as we and Laurel discover the truth.

In the end, Dix and Laurel’s relationship is destroyed by doubt, fear and distrust, even though he’s innocent, because she’s seen that other side of him. And even though Dix Steele doesn’t turn out to be the killer, this is far from a Hollywood happy ending. Very far from it.

The movie takes the basics of the book and adds an ambiguity that leads to a much more bittersweet and poignant story and ending than in the book. So this is a case where the filmmakers did change a certain essence of the story, but it works out for the better.

The movie is noir in the sense that Bogart is tripped up by his own Achilles Heel, his fatal flaw. To me, the thing that most makes something noir is not rain, not shadows, not femme fatales, not slumming with lowlifes. It’s a character who trips over their own faults: somebody who has some kind of defect, some kind of shortcoming, greed, want or desire…temper or insecurity, that leads them down a dark path, and then his or her life spins out of control because of their own weaknesses or failings. Here, Dix is innocent, but a loser, at least in a sense, and will always be a loser. His personality has driven away the one woman who really loved him. Love loses here too, as does Grahame’s character. Her inability to completely trust and believe in Dix leads to her losing what would have been the love of her life. It’s this ambivalence that make it a better movie than book, at least for me. There is, of course, much more to say about this movie, but my point in this piece is just to point out why I like the movie better than the book.

Dix and Laurel love each other, but they can’t be with each other—summed up in some famous lines from the film:

I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a

few weeks while she loved me.

Ultimately both versions need to stand on their own and they do. But for me, the bottom line is: I’d say: Good book, great movie.

***

***

Also, here are some pictures from my book signing last week with Pam Ripling at The Open Book in Valencia:

And my radio interview at KHTS AM 1220. Click here for the podcast.

Click here to: Subscribe to my Newsletter

Labels:

Dorothy B. Hughes,

film,

hardboiled,

In a Lonely Place,

noir,

Paul D. Marks,

writers,

writing

27 June 2016

Who Is At Fault?

by Jan Grape

A thirty-six year old woman was attempting to serve Court papers, on June 15th, at a northern Travis County home when she was attacked by six dogs. The attack resulted in her death.

The woman's family and the dog's owners were present at the hearing.

She didn't deserve to die and these dogs don't have a license to kill, the Judge said in making his ruling.

The Travis County medical examiner's office ruled that the dog's mauling caused the woman's death.

After the judge made his ruling the dog's chief owner said he would appeal the ruling.

No mercy was shown to our daughter so how can we show any mercy to these animals, the woman's parents said in a statement. She was innocent, doing her job. These dogs do not deserve to live. To euthanize them will be a small justice. Also it may prevent them from harming another person.

The dog's owner said his uncle and his wife were chief caretakers for the dogs and claims they are the victims. If she had heeded the warning signs that say, "NO Trespassing." This wouldn't have happened. The caretaker uncle is who found the woman's body.

Texas law states it doesn't matter whether or not a person has a right to be on a property in fatal dog maulings.

Four of the dogs are Labrador mixes and two are Australian cattle mixes. They range from two to six years old.

No word on when the dogs will be euthanized.

This was all taken from the Austin American-Statesman newspaper, Saturday, June 25, 2016

Maybe I'm strange but, personally I'm upset with the dog's owners and caretakers. Maybe they should be the ones euthanized. Somehow these owners trained or a least let the dogs understand that anyone who came on the property were to be attacked. I don't think dogs want or even think about harming a human. I suppose we'll never know if the dog owners's actually commanded the animals to "get" the woman.

I'm assuming this case isn't over and probably won't be for some time. I know other state's have laws that hold owners responsible for dog biting, mauling or killing a person. And unless I'm mistaken Texas law is that you must have your dog in your house on inside your fenced yard. The law also states you cannot have or keep your dog chained up.

I'm interested in knowing how my fellow sleuthsayers feel about this so please comment.

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX 78657, USA

26 June 2016

April in Manhattan

by R.T. Lawton

|

| AHMM editor Linda Landrigan at Notaro's Ristorante |

|

| 3 SleuthSayers at DELL reception R.T., Liz Zelvin & David Dean |

Supper that evening is with AHMM editor Linda Landrigan at Notaro's Ristorante, 635 2nd Avenue. This is a family owned business, the atmosphere is homey, the food is superb, the waiters are friendly and the prices are good. Try their Rigatoni alla Vodka with a glass of Pinot Noir. You'll come back to dine again. Even though we were all full, I got into a several minute discussion with our waiter about the Italian dessert Tiramisu and learned a few things. The waiter promptly returned with a plate of Tiramisu (on the house) and three forks. Best I've ever had, to include the one I ate in northern Italy where this dessert originated. Turns out our waiter is part of the family who owns the restaurant. It's not a large place, so I would recommend reservations. We will definitely eat there again.

|

| Some of the fancy dessert at Edgars Banquet. Edgar is white chocolate. |

Then, it's back to the Grand Hyatt for the Edgar Awards Banquet. The wife and I start with the Edgar Nominees Champagne Reception in a large room on the Ballroom level. As chief judge for the Best Novel category (509 hardcovers in ten months) it's interesting to meet and be able to chat with some of the Nominees. Best Novel Judges Brian Thornton and James Lincoln Warren are also in attendance.

|

| R.T. presenting to Edgars Best Novel Winner - Lori Roy |

|

| The Pond in Central Park |

|

| Reflections in Central Park |

|

| Baltika #3 in the Russian Vodka Room |

|

| SleuthSayer Brian Thornton & wife Robyn at Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal |

It was a great trip. If you haven't yet been to the Edgars, you should try it one of these Aprils. Just plan on spending some money.

Saturday is an early taxi ride back to La Guardia and a flight home.

Catch ya later.

Labels:

AHMM,

Alfred Hitchcock,

DELL Publishing,

Edgar Awards,

Linda Landrigan,

mystery magazine,

NYC,

R.T. Lawton

Location:

New York, NY, USA

25 June 2016

Damn Right, there's ME in my Characters!

Several times a year we do these reading and signing events. And people ask you a pile of questions about your books. Most are repeat queries that you’ve heard a

dozen times before. So you get pretty

good at answering them.

Lately, I was asked a question that I didn’t have a pat

answer to. In fact, it really made me

think.

“Do you make up all your characters, or do you put some of

yourself in them?”

I’d like to say that every character I write comes completely

from my imagination. For the most part,

they do. I can honestly say that I have

never seen a real person who matches the physical description of any of my

characters. (Not that I would mind

meeting Pete. But I digress…)

Back to the question:

are there bits of myself in my protagonists?

PROOF NO. 1 (others will follow in later posts)

“I am SO not a salad girl.”

Some people say this is one of the funniest lines in my

screwball mob comedy, THE GODDAUGHTER.

It is spoken by Gina Galla, goddaughter to the mob boss in Hamilton, the

industrial city in Canada near Buffalo, also known as The Hammer.

Gina is a curvy girl. She says

this line to her new guy Pete, as a kind of warning. And then she proceeds to tell him she wants a

steak, medium rare, with a baked potato and a side of mushrooms.

Apparently, that’s me.

So say my kids, spouse, and everyone else in the family.

Eat a meal of salad?

Are you kidding me? When there is

pasta, fresh panno and cannoli about? (I’ve

come to the conclusion that women who remain slim past the age of fifty must actually

like salad. Yes, it’s an astonishing

fact. For some people, eating raw green

weeds is not a punishment. )

Not me. I’m Italian,

just like my protagonist. We know our

food. Ever been to an Italian

wedding? First, you load up with

appetizers and wine, or Campari with Orange Juice if you’re lucky. When you are too stuffed to stand up anymore (why did you wear three inch

heals? Honestly you do this every time…) you sit down, kerplunk. Bring on the antipasto. Meat, olives, marinated veggies, breadsticks,

yum. Melon with prosciutto. Bread with olive oil/balsamic vinegar

dip. White wine.

Then comes the pasta al olio. Sublime.

Carbs are important fuel, right?

And I’m gonna need that fuel to get through the main course, because

it’s going to be roast chicken, veal parmesan, osso buco, risotto, polenta, stuffed

artichokes (yum), more bread, red wine.

Ever notice that salad is served after the main course in an

Italian meal? Good reason for that. We aren’t stupid. Hopefully, you will have no room left for it.

So yes, my protagonist Gina shares an important trait with

me. She likes meat, dammit.

So you can be a bunny and eat salad all you like. Bunnies are cute and harmless.

But Gina and I are more like frontier wolves. Try making us live on salad, and see how

harmless we will be.

Which is what you might expect from a mob goddaughter from

The Hammer.

Do you find bits of

yourself sneaking into your fiction?

Tell us here, in the comments.

Melodie

Campbell writes the award-winning Goddaughter mob comedy series,

starting with The Goddaughter which happens to be on sale now for $2.50. Buy it. It's an offer you can't refuse.

P.S. My maiden name was 'Offer.' No joke. Although I've heard a few in my time.

P.S. My maiden name was 'Offer.' No joke. Although I've heard a few in my time.

Labels:

characters,

creative writing,

fiction,

Italy,

Melodie Campbell,

protagonists,

readings,

signings,

writing

24 June 2016

Genre-Bending Brilliance: An Interview with Ariel S. Winter

by Art Taylor

Ariel S. Winter’s debut novel, The Twenty-Year Death, was actually a trilogy of novels, bound in a single volume, each in turn paying homage to a classic crime writer—Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and Jim Thompson, specifically—and together telling the full story of the beautiful Clothilde-ma-Fleur over two decades, from France in 1931 to Hollywood in 1941 to Baltimore in 1951. I reviewed the book for the Washington Post in 2012 and found it a truly stunning tour de force, a masterful achievement.

This spring, Winter returned with a second book, Barren Cove—which is equally (if not as epically) magnificent but which also shows Winter taking his talent in a different direction. Instead of a crime novel, Barren Cove is more solidly a family drama; a visitor staying in the guest cabana of a Victorian estate interacts with the mysterious and clearly troubled family living in the main house: the beautiful and haunted Mary, her larger-than-life brother Kent, the mischievous Clark, and then the reclusive Beachstone, whom the property is named after but whose sickness keeps him hidden away in his room.

Oh, and one more thing: Nearly all these characters—everyone but Beachstone—are robots.

Winter offered me the chance to speak with him about the new book—thrilling in many ways from a writer’s perspectives (and a reader's too, I should stress) but also challenging in a world where branding and marketing and categories are the order of the day.

ART TAYLOR: Barren Cove clearly signals a shift in genre, with its futuristic setting, with robots as the primary characters, even in the labeling with "science fiction” mentioned prominently in one of the back cover blurbs. Have you been as big a reader and a fan of science fiction as you are of mystery fiction? Are there specific authors here, as with The Twenty-Year Death, that was an influence?

ARIEL S. WINTER: I became a writer because of my great love of reading, and as a reader I've never limited myself to specific genres. Especially as a kid, I read fantasy, science fiction, mystery, comedy, literary fiction, pretty much anything my parents or librarians recommended, plus whatever I stumbled on myself. And lots and lots of comic books. Since all of those genres fueled my love of fiction, and my writing grew out of my love of fiction, it only makes sense that my writing encompasses all of the things that turned me into a writer in the first place.

Growing up, I read the classics, Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, Douglas Adams, several of whom I pay homage to in Barren Cove through characters' names. Then as I got older I moved on to Philip K. Dick, Jonathan Lethem, Alfred Bester, Thomas M. Disch, and I'm still filling in some of the gaps in my reading. I finally read the Dune books last year and was blown away.

As for influence on Barren Cove, it's less about style, and more about world building. I imagined that all robot fiction up to now takes place in a shared universe, so that the great robot books are detailing a continuous history. In R.U.R. by Karel Capek, the action takes place exclusively in a factory where robots are just first starting to be manufactured. By I, Robot, robots are an integral part of human life, but the laws of robotics put limits on their actions, and helps to keep them separate from humans. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? robots are indistinguishable from humans, even passing as human, and they are pervasive, but they're supposed to still be inferior socially. Barren Cove is the next book in that history, the point at which robots are now the majority, and humans are second-class.

While your two books might seem to readers very different, the interest in genre seems a central connection—not just in the specific genres of police procedural or hard-boiled detective novel or noir or science fiction, but in the idea of genre itself: what constitutes genre, how are specific genres defined, how does all this guide reader expectations. My questions for you: What is it about genre more generally that interests you and drives your writing? Is it exploration, experimentation, commentary on genres and genre-building or…?

I've always been excited by books that push the boundaries of form. Writers like Mark Z. Danielewski with his typography and page layouts, David Mitchell with his genre jumping within a single book, and writers like Faulkner, B.S. Johnson, Jan Potocki, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Laurence Sterne. Two of my favorite books, and the ones that probably had the greatest influence on Barren Cove are Frankenstein and Wuthering Heights, both of which play with multiple narrators, frame stories, several different forms such as journals, letters, and stories given orally that were subsequently written down, adding another layer to the trustworthiness of the story itself. So form is usually as big a driving factor in my work as genre is. And since genre carries with it certain expectations and conventions, it gives some kind of structure on which to lay formal experimentation. That makes it sound like genre is merely a tool though, and that's not right, because it goes back to wanting to write the kind of books I love, which are broadly defined, as I said earlier. I usually start with genre in the same way that I would decide to pick up one book or another to read, simply because it seems cool. Then as I explore the genre, I like to challenge it.

“Branding” is a big buzzword for authors today. After all the recognition you earned for The Twenty-Year Death, did you feel any pressure—from your editor or your agent or from readers or from self—to write another crime novel? Or any opposition to the book here that you did write?

The short answer is “yes.” The book that my agent and I tried to sell after The Twenty-Year Death was actually a domestic drama, literary fiction. We got some excellent feedback, several editors who were very serious about it, but they just couldn't sell it to their marketing and sales teams because it wasn't a mystery, and I was a mystery writer, even though I'd only published one book. In frustration, I pulled out Barren Cove, which I originally wrote in 2004, expanded it quite a bit, and we then went out with that. It was still a different genre, but it was mostly finished, and we could go out with it quickly. We met with a lot of the same resistance. People loved it, but it wasn't a mystery. I was lucky enough to finally find editors who were willing to take the risk, but it proved a real challenge for marketing, and it's met with mixed results. I've had to admit that while I insisted that a writer can jump genres, I've sort of been proven wrong. That's not because readers won't read across genres, which was a lot of my argument, because of course they will. But that the book publishing world from marketing to reviewers to bookstores are separated by genre so much that it isn't a question of finding readers who will follow you, but rather, of having access to the same people who covered your previous books in the press. It's a lot about the network. So, yes, I'm now being gently encouraged to return to crime. I've spent the last few years working on a fantasy, but that might get put on hold.

While the narrator and most of the characters in Barren Cove are robots, their struggles—both the conflicts between characters and then their internal, existential troubles—seem all too human. Ultimately, this is a story about identify and family and relationships. Why not just write a family drama? one without robots?

Someone asked me that at a social event a few years ago, and I was really taken aback, because it was such an astute question, especially given that she hadn't read the book. The answer is because robots can be immortal, replacing parts and upgrading indefinitely, and the possibility of immortality, which you can't have with human characters, really changes the nature of the existential question about death. If you don't have to die except by choice, why would you ever choose to die? It's a different question than we usually ask.

I also used robots, because as I said before, I like books with an unreliable narrator, which can sometimes be chalked up to a question of memory. But robots have perfect memories, so how accurate is a story when the memory is perfect? At the same time, however, robots, as computers, can have their memories erased or rewritten, so how trustworthy are they then?

I used the word “existential” before—but it’s not just questions of existence but also concerns about mortality, about death, that stood out to me reading it. What themes or issues drove you in writing this story? Or do you even think of themes in that way when you’re writing?

So I either start with genre or story, and that was the same here. I wanted to write something like a number of books I loved, so I looked at Wuthering Heights and Philip K. Dick and others, and said, I want to do something like this. The themes then develop organically in the writing. I'm not like Cormac McCarthy who seems to build a story around the idea of fate. Instead I build a story, and since I try to keep the stakes high, themes emerge. In The Twenty-Year Death, that became about losing a family member. In Barren Cove it became a question of why do we live. Then I go back and accentuate it in the rewrites. That being said, it's more important to me that a book is fun to read, that the story is compelling, than whether it's conveying an idea, so I try to use that as my guiding principle throughout.

This spring, Winter returned with a second book, Barren Cove—which is equally (if not as epically) magnificent but which also shows Winter taking his talent in a different direction. Instead of a crime novel, Barren Cove is more solidly a family drama; a visitor staying in the guest cabana of a Victorian estate interacts with the mysterious and clearly troubled family living in the main house: the beautiful and haunted Mary, her larger-than-life brother Kent, the mischievous Clark, and then the reclusive Beachstone, whom the property is named after but whose sickness keeps him hidden away in his room.

Oh, and one more thing: Nearly all these characters—everyone but Beachstone—are robots.

Winter offered me the chance to speak with him about the new book—thrilling in many ways from a writer’s perspectives (and a reader's too, I should stress) but also challenging in a world where branding and marketing and categories are the order of the day.

ART TAYLOR: Barren Cove clearly signals a shift in genre, with its futuristic setting, with robots as the primary characters, even in the labeling with "science fiction” mentioned prominently in one of the back cover blurbs. Have you been as big a reader and a fan of science fiction as you are of mystery fiction? Are there specific authors here, as with The Twenty-Year Death, that was an influence?

|

| Ariel S. Winter |

Growing up, I read the classics, Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, Douglas Adams, several of whom I pay homage to in Barren Cove through characters' names. Then as I got older I moved on to Philip K. Dick, Jonathan Lethem, Alfred Bester, Thomas M. Disch, and I'm still filling in some of the gaps in my reading. I finally read the Dune books last year and was blown away.

As for influence on Barren Cove, it's less about style, and more about world building. I imagined that all robot fiction up to now takes place in a shared universe, so that the great robot books are detailing a continuous history. In R.U.R. by Karel Capek, the action takes place exclusively in a factory where robots are just first starting to be manufactured. By I, Robot, robots are an integral part of human life, but the laws of robotics put limits on their actions, and helps to keep them separate from humans. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? robots are indistinguishable from humans, even passing as human, and they are pervasive, but they're supposed to still be inferior socially. Barren Cove is the next book in that history, the point at which robots are now the majority, and humans are second-class.

While your two books might seem to readers very different, the interest in genre seems a central connection—not just in the specific genres of police procedural or hard-boiled detective novel or noir or science fiction, but in the idea of genre itself: what constitutes genre, how are specific genres defined, how does all this guide reader expectations. My questions for you: What is it about genre more generally that interests you and drives your writing? Is it exploration, experimentation, commentary on genres and genre-building or…?

I've always been excited by books that push the boundaries of form. Writers like Mark Z. Danielewski with his typography and page layouts, David Mitchell with his genre jumping within a single book, and writers like Faulkner, B.S. Johnson, Jan Potocki, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Laurence Sterne. Two of my favorite books, and the ones that probably had the greatest influence on Barren Cove are Frankenstein and Wuthering Heights, both of which play with multiple narrators, frame stories, several different forms such as journals, letters, and stories given orally that were subsequently written down, adding another layer to the trustworthiness of the story itself. So form is usually as big a driving factor in my work as genre is. And since genre carries with it certain expectations and conventions, it gives some kind of structure on which to lay formal experimentation. That makes it sound like genre is merely a tool though, and that's not right, because it goes back to wanting to write the kind of books I love, which are broadly defined, as I said earlier. I usually start with genre in the same way that I would decide to pick up one book or another to read, simply because it seems cool. Then as I explore the genre, I like to challenge it.

“Branding” is a big buzzword for authors today. After all the recognition you earned for The Twenty-Year Death, did you feel any pressure—from your editor or your agent or from readers or from self—to write another crime novel? Or any opposition to the book here that you did write?

The short answer is “yes.” The book that my agent and I tried to sell after The Twenty-Year Death was actually a domestic drama, literary fiction. We got some excellent feedback, several editors who were very serious about it, but they just couldn't sell it to their marketing and sales teams because it wasn't a mystery, and I was a mystery writer, even though I'd only published one book. In frustration, I pulled out Barren Cove, which I originally wrote in 2004, expanded it quite a bit, and we then went out with that. It was still a different genre, but it was mostly finished, and we could go out with it quickly. We met with a lot of the same resistance. People loved it, but it wasn't a mystery. I was lucky enough to finally find editors who were willing to take the risk, but it proved a real challenge for marketing, and it's met with mixed results. I've had to admit that while I insisted that a writer can jump genres, I've sort of been proven wrong. That's not because readers won't read across genres, which was a lot of my argument, because of course they will. But that the book publishing world from marketing to reviewers to bookstores are separated by genre so much that it isn't a question of finding readers who will follow you, but rather, of having access to the same people who covered your previous books in the press. It's a lot about the network. So, yes, I'm now being gently encouraged to return to crime. I've spent the last few years working on a fantasy, but that might get put on hold.

While the narrator and most of the characters in Barren Cove are robots, their struggles—both the conflicts between characters and then their internal, existential troubles—seem all too human. Ultimately, this is a story about identify and family and relationships. Why not just write a family drama? one without robots?

Someone asked me that at a social event a few years ago, and I was really taken aback, because it was such an astute question, especially given that she hadn't read the book. The answer is because robots can be immortal, replacing parts and upgrading indefinitely, and the possibility of immortality, which you can't have with human characters, really changes the nature of the existential question about death. If you don't have to die except by choice, why would you ever choose to die? It's a different question than we usually ask.

I also used robots, because as I said before, I like books with an unreliable narrator, which can sometimes be chalked up to a question of memory. But robots have perfect memories, so how accurate is a story when the memory is perfect? At the same time, however, robots, as computers, can have their memories erased or rewritten, so how trustworthy are they then?

I used the word “existential” before—but it’s not just questions of existence but also concerns about mortality, about death, that stood out to me reading it. What themes or issues drove you in writing this story? Or do you even think of themes in that way when you’re writing?

So I either start with genre or story, and that was the same here. I wanted to write something like a number of books I loved, so I looked at Wuthering Heights and Philip K. Dick and others, and said, I want to do something like this. The themes then develop organically in the writing. I'm not like Cormac McCarthy who seems to build a story around the idea of fate. Instead I build a story, and since I try to keep the stakes high, themes emerge. In The Twenty-Year Death, that became about losing a family member. In Barren Cove it became a question of why do we live. Then I go back and accentuate it in the rewrites. That being said, it's more important to me that a book is fun to read, that the story is compelling, than whether it's conveying an idea, so I try to use that as my guiding principle throughout.

23 June 2016

Gods and Demi-Gods

by Eve Fisher

Ever since the Orlando shooting, I've seen a lot more memes about how America doesn't need more laws, it needs to turn back to God. But America has turned completely to its gods, which are money and power. We sacrifice human beings on their altars every day, and guns are one of the ways we do it. We swallow the deaths of 20 children, 50 people, a mass shooting every day, without a qualm because we know our gods are righteous and just and POWERFUL. Money and power require these (and other) human sacrifices, because otherwise we would not realize how powerful - and false - these gods are. Their worship is mediated through their denominations, (the modern, international corporations), their priesthood (lobbyists and politicians), and their demi-gods (celebrities and millionaires/billionaires).

Propaganda: The poor are "losers", "moochers", "lazy", "worthless", "stupid". Social Security and Medicare - both fully taxpayer funded, i.e., paid by us - are called "entitlements", which implies that they haven't been earned, but are something we moochers wrongly feel "entitled" to. (Damn straight I feel "entitled" to Social Security - I paid into it for 40 years!)

Political restrictions: Between gerrymandering, voting restrictions, and Citizens United, the powerful have done an excellent job of ensuring that the votes/interests/representation of the working class and poor are rendered irrelevant to the political process. My own congresspeople - John Thune, Mike Rounds, and Kristi Noem - respond to my e-mails and letters with form letters. I don't have the money to make them hear me.

Legal restrictions:

But fear counts above all. No one must ever question why - living in the richest, most privileged, most free society on earth, the "home of the free and the brave" - why they are so afraid, all the time, everywhere. And, why is the object of fear constantly changing? In Orwell's "1984" Oceania always at war, but the enemy kept switching from Eurasia to Eastasia. In my lifetime I have watched the enemy - the one who will destroy us at all costs - change from Communism to the Evil Empire (Soviet Russia)/China to Japan to the Axis of Evil (Iran/Iraq/North Korea) to Saddam Hussein to Osama bin Laden to Radical Islamic Terrorism, with a few stops along the way at black ghettos, hippies, drugs, black gangs, urban thugs, illegal immigrants, illegal immigrant children, legal refugees, and anyone wearing a turban. Not to mention polio, HIV, SARS, H1N1, Ebola, and Zika viruses.

But fear counts above all. No one must ever question why - living in the richest, most privileged, most free society on earth, the "home of the free and the brave" - why they are so afraid, all the time, everywhere. And, why is the object of fear constantly changing? In Orwell's "1984" Oceania always at war, but the enemy kept switching from Eurasia to Eastasia. In my lifetime I have watched the enemy - the one who will destroy us at all costs - change from Communism to the Evil Empire (Soviet Russia)/China to Japan to the Axis of Evil (Iran/Iraq/North Korea) to Saddam Hussein to Osama bin Laden to Radical Islamic Terrorism, with a few stops along the way at black ghettos, hippies, drugs, black gangs, urban thugs, illegal immigrants, illegal immigrant children, legal refugees, and anyone wearing a turban. Not to mention polio, HIV, SARS, H1N1, Ebola, and Zika viruses.

- The first thing to understand is that when money and power are gods, ALL corporations must make constant profits: the latest economic doctrine - "maximizing shareholder value" - says that a corporation has no purpose but to make profits for its shareholders. This means that employer/employee loyalty and customer service/satisfaction are both irrelevant. Pensions and/or health benefits can and must be cut whenever it's expedient to the bottom line. Jobs must be outsourced to the lowest bidder, taxes must be avoided by offshoring whenever possible, nationalism/patriotism is a 20th century concept (i.e., ridiculous) and the fact that unemployed people do not buy much is ignored. The honest truth is the United States is no longer the preferred customer of most corporations, including Coca-Cola: China is king.

- When money and power are gods, everything must be privatized, i.e., put into the hands of corporations. At the same time, the corporations are no longer national, they are global, in order to maximize shareholder value (see above). Government - on any level - is an impediment to profit, so it must be made as small and neutralized as possible, except when needed to help the corporations (see below).

- NOTE: I am constantly amazed at how, in one of the most successful propaganda campaigns in history, our government (a democracy, where the government is "we, the people") has become more dangerous in many people's eyes than corporations such as Monsanto, R. J. Reynolds, Dow Chemical, and Smith & Wesson. At least with government, I can vote the bastards out: corporations, can't even be sued any more (see Legal Restrictions below).

- Corporate profits must be maintained, at all costs, including military. Eisenhower recognized the beginnings of this in his Military Industrial Complex Speech. Since the end of the Cold War, there has almost always been an economic rather than political reason why troops are sent where they are, why outrage is expressed over certain international incidents and not over others. (This is why, for example, the entire international community joined the United States to invade Iraq in 1990-91's First Gulf War, a/k/a the 710 War, but everyone stood on the sidelines and watched as 800,000 people were slaughtered in the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.) And many aspects of war - supplies, security, etc. - are now routinely privatized to corporations which make a hefty profit with almost no oversight, including Bechtel (which was accused of war profiteering), Halliburton, and Blackwater (which was brought before Congress in 2007 for "employee misdeeds," among other things).

- NOTE: In the run-up to the Iraq war, Halliburton was awarded a $7 billion contract for which 'unusually' only Halliburton was allowed to bid (Wikipedia - Halliburton) It might not have hurt that Dick Cheney had been Chairman and CEO from 1995-2000.

- The gun manufacturers and armament industries must make constant profits, which means sales must be constant, and so the NRA preaches the complete and total ownership of any firearm of any kind by anyone at any time. (Soon coming to your neighborhood: personal flamethrowers! Sadly, I'm not kidding.) That's why each new shooting must be propagandized in whatever way that will increase sales:

- there are crazy people out there with guns, buy more guns now;

- the terrorists are coming to kill you, buy more guns now;

- the government is coming to take away your guns, buy more on guns now.

- Also, to ensure constant profits for the weapons industry, our entertainment and news media must be saturated with ever-increasing levels of threats and violence both to keep the fear and anxiety at suitable levels and - very important, very underestimated - product placement. (Remember that every prop / weapon / outfit / drink you see on Criminal Minds, James Bond, the Bourne Identities, etc., is there in order to sell one to you.)

- NOTE 1: If you don't believe that violence in media has any effect on people's behavior, then why do corporations spend billions on advertising? If the constant barrage of news feeds, hour-long TV show, binge-watching television shows, and movies, or unlimited video games has no effect on our minds and behavior, then why should corporations pay billions for a 30-second ad spot? Why do politicians and super-PACs do the same? Are they all stupid?

- NOTE 2: If you don't believe that violence in media has increased, watch an episode of Gunsmoke on RetroTV some time, and note how seldom Matt Dillon (or even the bad guys) used a gun. Some day count the number of weapons on display in previews during the morning news. (The average child will see 8,000 murders on television before finishing elementary school: Link).

When money and power are gods, and corporations are their high priests, it has real world consequences. And one of those is that the poor - collectively and individually - are sinners, and must be punished by any means at the disposal of the powerful. The results are:

- NOTE 3: The quantity of violence not only has increased, but, as the public becomes more jaded, it has become more and more perverse. On the news, "When it bleeds, it leads!" Literally. As for entertainment, in the 1980s, Law and Order SVU was considered fairly hard-core, with story-lines of children being abused and murdered, women and children being raped, tortured, etc. Not any more. Criminal Minds, Dexter, Hannibal, and other shows upped the ante with on-screen cannibalism, eye-gougings, etc. On "Game of Thrones" human beings are being castrated and flayed alive. Live, to-the-death gladiatorial contests cannot be far behind. (But it's all in jest, they but do poison in jest, no harm in the world...)

Propaganda: The poor are "losers", "moochers", "lazy", "worthless", "stupid". Social Security and Medicare - both fully taxpayer funded, i.e., paid by us - are called "entitlements", which implies that they haven't been earned, but are something we moochers wrongly feel "entitled" to. (Damn straight I feel "entitled" to Social Security - I paid into it for 40 years!)

Political restrictions: Between gerrymandering, voting restrictions, and Citizens United, the powerful have done an excellent job of ensuring that the votes/interests/representation of the working class and poor are rendered irrelevant to the political process. My own congresspeople - John Thune, Mike Rounds, and Kristi Noem - respond to my e-mails and letters with form letters. I don't have the money to make them hear me.

Legal restrictions:

- Our right to sue corporations is being stripped away from us by "mandatory arbitration clauses" put in place by most health insurance plans, dealership or franchise agreements, billing agreements (think credit cards), and many, many, many other corporate contracts. These deny the right of the consumer, employee, or contractee to sue in favor of arbitration before an arbiter of the corporation's choosing, at your expense (think $200-$300 an hour). See Public Citizen Access - Mandatory Arbitration Clauses.

- Gag orders have become common as part of settlements with large corporations. See Fracking gag order.

- If you are poor and arrested, even if you are found innocent, in many states and counties, you will be charged with court costs, fines, and fees for your (hopefully short) stay in jail. In some counties, you will be charged for a public defender, despite the Miranda Law's assurance that one will be provided for you.

- The prison system - which has been privatized in many states - must make constant profits, and their contracts require full prisons, no matter what the level of crime actually is. Therefore any laws which decriminalize any drugs must be fought. Also, addiction, mental illness, and mental disability have been unofficially criminalized, because there's not enough money for state or federal mental health facilities and private mental health facilities are only for those with excellent health insurance.

But fear counts above all. No one must ever question why - living in the richest, most privileged, most free society on earth, the "home of the free and the brave" - why they are so afraid, all the time, everywhere. And, why is the object of fear constantly changing? In Orwell's "1984" Oceania always at war, but the enemy kept switching from Eurasia to Eastasia. In my lifetime I have watched the enemy - the one who will destroy us at all costs - change from Communism to the Evil Empire (Soviet Russia)/China to Japan to the Axis of Evil (Iran/Iraq/North Korea) to Saddam Hussein to Osama bin Laden to Radical Islamic Terrorism, with a few stops along the way at black ghettos, hippies, drugs, black gangs, urban thugs, illegal immigrants, illegal immigrant children, legal refugees, and anyone wearing a turban. Not to mention polio, HIV, SARS, H1N1, Ebola, and Zika viruses.

But fear counts above all. No one must ever question why - living in the richest, most privileged, most free society on earth, the "home of the free and the brave" - why they are so afraid, all the time, everywhere. And, why is the object of fear constantly changing? In Orwell's "1984" Oceania always at war, but the enemy kept switching from Eurasia to Eastasia. In my lifetime I have watched the enemy - the one who will destroy us at all costs - change from Communism to the Evil Empire (Soviet Russia)/China to Japan to the Axis of Evil (Iran/Iraq/North Korea) to Saddam Hussein to Osama bin Laden to Radical Islamic Terrorism, with a few stops along the way at black ghettos, hippies, drugs, black gangs, urban thugs, illegal immigrants, illegal immigrant children, legal refugees, and anyone wearing a turban. Not to mention polio, HIV, SARS, H1N1, Ebola, and Zika viruses. - NOTE: So far, we're still here.

- Money and power are abstractions, fictions, a belief system rather than a reality, to which we sacrifice real human beings, not to mention real air, real water, real food, real life, daily.

- No matter how much money and power is worshiped, acquired, accumulated, fought for, praised, and sacrificed to, life will never be 100% safe, and 100% of all people will all still die naked and alone. Including the wealthiest of the 1%. The gods of money and power, the church of the corporation, the priests of politicians and lobbyists, the demi-gods of celebrity will not save any of us from that fate.

Labels:

celebrities,

entitlement,

Eve Fisher,

genocide,

guns,

money,

war

22 June 2016

Writers League of Texas Agents & Editors Conference

by Velma

by Jan Grape and Velma

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Location:

Austin, TX, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)