"I can't access the fingerprint files," Phil said.

Sally fisted her hair. "Oh, no! That could negatively impact our investigation!"

Should I contact the lieutenant?" Fred asked.

"I'm efforting that right now," Phil assured him.

In this brief but thrilling bit of dialogue, I have verbed five nouns.

That is, I have taken five words once firmly ensconced in the language

as nouns, and I have used them as verbs. This sort of verbing

seems to be going on a lot these days. We read newspaper articles about

the benefactor who gifted the museum with a valuable painting, about the county office transitioning to a new computer system. And of course almost all of us speak of texting people and friending people. Some of

us say we Facebook.

Should we accept the verbing trend as inevitable, perhaps desirable? Should we resist it? Does resistance make sense in some cases but not in others? Writers, including mystery writers, probably have some influence on the ways in which language changes, perhaps more influence than we realize. So maybe, before we let ourselves slip into following a linguistic trend, we're obliged to examine it carefully, to think about whether it's a change for the better.

Should we accept the verbing trend as inevitable, perhaps desirable? Should we resist it? Does resistance make sense in some cases but not in others? Writers, including mystery writers, probably have some influence on the ways in which language changes, perhaps more influence than we realize. So maybe, before we let ourselves slip into following a linguistic trend, we're obliged to examine it carefully, to think about whether it's a change for the better.

Obviously, there's nothing unusual or improper about a word functioning as more

than one part of speech. "He decided to turn off the ceiling light and

light the candles, while his wife, wearing a light blue dress, fixed a

light supper." Here, in one sentence, "light" serves as noun, verb,

adverb, and adjective--repetitive, but not ungrammatical or unclear. And I think we'd all agree language is a living thing that needs to change

to meet new needs. Many would argue (and I'd agree) that the English

language, especially, is vital and expressive precisely because it's

always been so flexible and open, so ready to absorb useful words from

other languages and to adjust to changing conditions. Sometimes, change

means inventing new words to describe new things--telephone, astronaut,

Google. Sometimes, it means using existing words in new ways--text,

tablet, tweet. These sorts of changes in the language reflect changes in reality. Some of them may enrich the language; some may make it sillier or less euphonious. Either way, trying to resist them is probably pointless.

Is verbing such a change? In some cases, I think, it probably is. Consider the first sentence in the opening dialogue. "Access" used to be a noun and nothing but a noun. Fowler's Modern English Usage (I've got the second edition, published in 1965, inherited from my English professor father) draws careful distinctions between access and accession, showing scorn for those who "carelessly or ignorantly" confuse the two. Fowler doesn't even consider the possibility that anyone might use "access" as a verb. One might need a key to gain access to the faculty washroom, but the idea that anyone might access the washroom--no. Today, though, when almost all of us use computers and often have trouble getting at what we want, using "access" as a verb seems natural. Yes, Phil could say he can't gain access to the fingerprint files, but the extra words feel cumbersome here, an inappropriate burden on a process that should take seconds. Old fashioned as I am, I think using "access" as a verb might be a sensible, useful adjustment to change.

Back to the opening dialogue: Sally fears not being able to access the fingerprint files "could negatively impact our investigation." I think some writers use "impact" as a verb because, like "fist," it sounds sexy and forceful, sexier and more forceful than "affect" or "influence." But does it convey any meaning those words don't? If not, I'm not sure there's an adequate reason for creating a new verb. And if we have to modify "impact" with an adverb such as "negatively" to make its meaning clear, wouldn't it be more concise to choose a specific one-word verb such as "hurt" or "stall"--or "end," if the negative impact will in fact be that bad? Again, I'd say "impact" is a verb we can do without. It answers no need our existing verbs fail to meet. It adds nothing to the language.

What about "contact"? In the opening dialogue, Fred asks if he should "contact" the lieutenant. Like "access," "contact" was once a noun and nothing else. Is there a problem with using it as a verb as well? Strunk and White think so. In the third edition of Elements of Style (a relic from my own days as an English professor), they (or maybe just White) declare, "As a transitive verb, [`contact'] is vague and self-important. Do not contact anybody; get in touch with him, or look him up, or phone him, or find him, or meet him." Or, in this situation, Fred might ask if he should inform the lieutenant, or warn her, or ask her for advice. "Contact" is pretty well established as a verb by now, but I think the argument that it's "vague and self-important" still holds. "Contact" is a lazy verb. It doesn't meet a new need--it just spares us the trouble of saying precisely what we mean. Even if few readers would object to using "contact" as a verb these days, writers who want to be clear should still search for a more specific choice.

Then there's "effort." What possible excuse can there be for transforming this useful noun into a pretentious verb? In the second edition of Common Errors in English Usage (a wonderful resource), Paul Brians declares such a transformation "bizarre and unnecessary": "You are not `efforting' to get your report in on time; you are trying to do so. Instead of saying `we are efforting a new vendor,' say `we are trying to find a new vendor.'" Maybe some people think "efforting" will make it sound as if they're working harder. If so, they can always say they're "striving" or "struggling"--but those words will be obviously inappropriate if not much work is actually involved, if they're just making a phone call. Is "efforting" appealing because it lets us get away with making simple tasks seem more arduous than they really are? If so, we should definitely resist the temptation to inflate the importance of what we're doing by using a fancy new verb.

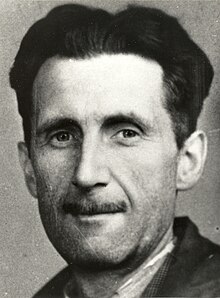

By now, some may be wondering if any of this matters. If we want to dress up our sentences by turning some nouns into impressive-sounding new verbs, so what? Where's the harm in that? George Orwell provides an answer in his classic "Politics and the English Language." I can't summarize his subtle, complex argument here; I can only offer a quotation or two and urge anyone who hasn't already read the essay to do so. Just as ideas can influence language, Orwell argues, language can influence ideas. The English language "becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts." Nor should we surrender to damaging trends in language because we assume resistance is futile. "Modern English, especially written English," Orwell says, "is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble." As writers, perhaps we have a special responsibility to protect the language by setting a good example. At least we can effort it.

Oops. Sorry. At least we can try.

Great piece, B.K. Love the Orwell quote.

ReplyDeleteA nice piece. We live in an age of toxic language inflation.

ReplyDeleteSometimes it hurts to be a college English or communications teacher! BK - I can really relate to this post. I wouldn't mind so much if my students knew what they were doing to the language. But what burns me is they can't tell a verb from a noun, because they were never taught the parts of speech.

ReplyDeleteOkay, enough rant from this prof! Back to my writing cave...

--Paul, thanks for your comment. I think "Politics and the English Language" is an amazing essay--written almost seventy years ago, but as timely as ever.

ReplyDelete--Janice, I love the phrase "toxic language inflation." I think "inflation" is the perfect way to describe the source of many abuses of language. People dress language up not to express their meaning more precisely but to make sentences that don't mean much sound more impressive.

--Melodie, I share your frustration. It's hard to teach a college-level course when one is forced to spend half the semester teaching things students should have learned in high school.

Hi, B.K.,

ReplyDeleteWe've been told that verbs need to be active. One way is to use nouns as verbs giving language more flexibility.

Thanks for your comment, Jacquie. I agree that it's good for language to be flexible. If using a noun as a verb allows us to express an idea we couldn't otherwise express as clearly or concisely, I've got no objection. I think "access" passes that test. I do have reservations when people use nouns as verbs to avoid the need to be specific ("contact") or to make something simple seem more impressive or powerful than it really is ("effort," "impact").

ReplyDeleteI’m guilty of using access and contact as verbs, but I’m with you. I wonder if ‘efforting’ was some way conflated or confused with ‘effecting’?

ReplyDeleteBesides ‘gifted’, ‘party’ is a verbulated noun that drives me crazy. I once heard a 20s-something guy use ‘harsh’ as a verb: “She harshed on him.” I supposed that’s a verbized adjective.

James Lincoln Warren argued verbed nouns were a natural evolution of language, but you never knew if he was ornerinessing.

While I’m at it, I’d like to complain about the Oxford English Dictionary treatment of ‘nonplussed’. The small electronic edition I use says:

“In standard use, nonplussed means ‘surprised and confused’: the hostility of the new neighbor's refusal left Mrs. Walker nonplussed. In North American English, a new use has developed in recent years, meaning ‘unperturbed’—more or less the opposite of its traditional meaning: hoping to disguise his confusion, he tried to appear nonplussed. This new use probably arose on the assumption that non- was the normal negative prefix and must therefore have a negative meaning. It is not considered part of standard English.”

I have never heard this so-called North American use (please don’t prove me wrong) except in the Oxford English Dictionary.

I picked up a Writers Digest book from Amazon’s bargain bin offering advice on writing. Following SleuthSayers guidelines, I won’t mention the author (and I see at least three other books of the same title), but after only two chapters, I was aghast.

ReplyDeleteThe author, apparently a professor, criticizes ‘old’ writing and promotes new, fresh, modern writing: Don’t hesitate to break old-fashioned rules. Fair enough, but while calling the reader ‘dude’ (really!), he goes on to recommend ditching obsolete punctuation like colons, semicolons, and parentheses. Even that’s tolerable under the right circumstances, but unlike your examples, Barb, he doesn’t like verbs.

Instead. He loves. Incomplete sentences.

Sentence fragments, good. Complete sentences, bad. Obsolete. Old fashioned. So yesteryear.

Clearly this expert is so tone deaf, he doesn’t realize the reader has to pause, re-parse the words, and try to figure out what the writer is trying to say. Ironically his attempts to be modern give the book a late 1980s / early 1990s feel.

He offers some bits of reasonable advice (use 'said' and no other speech tags) but he's also loaded with bad advice. I read two chapters and didn't feel like I could take much more. But I bet his ignore-the-rules advice sells a lot to self-pubbers.

Leigh, I've never heard of that "North American" usage of `nonplussed,' either. Should I say that Oxford English Dictionary entry leaves me feeling plussed?

ReplyDeleteAnd I'm prepared to fight to the death for the right to use colons, semicolons, and parentheses--I find them all useful, and (as you can see)I like dashes, too. As for sentence fragments, I think an occasional one is fine, especially in dialogue, but too many can make prose seem self-conscious and artificial.

Turning adjectives into verbs sounds like a very, very bad idea. I'm also not crazy about turning verbs into nouns. When I worked in a college advancement office (a.k.a. fundraising office), people spoke of "making the ask." Good grief. And I cringe when publishers refer to a "cover reveal." We are living through dark, troubled times.

Great column, Bonnie! I can't help thinking about the times all my Baptist friends use nouns as verbs: "We'll meet afterward and fellowship," or "I think we should dialogue about that." Good grief.

ReplyDeleteI don't usually mind nouns being used as verbs--contact, access, house, balloon, phone, hammer, etc. etc.--but some of them just sound wrong, like--as you said--"effort."

Is it just me who's having giggling fits over one of these words in a very adult context?

ReplyDeleteGreat post! Some verbing annoys me, but I don't know why, when others do not. I would consider my context and could conceive of places where I'd use even the ones that make my skin crawl. I would give those to the dialogue or POV of an unsavory character. Sometimes I want a pretentious character to use words wrongly, so anything goes there. I love the English language, even as it evolves.

ReplyDeleteI find it funny that Strunk and/or White said not to contact someone. Phone him instead. As if phone isn't a noun that was verbed...And when did the wonderful noun "verb" become a verb anyway?

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comments, everybody. John, I'd never before heard "fellowship" used as a verb, but I have heard academics say they're going to workshop or to conference. Anonymous, I wish I knew which word you have in mind--I'd enjoy a good giggle. Barb, I think Strunk and White object to "contact" as a verb not so much because it started as a noun but because it's vague. "Phone" refers to a specific action; "contact" spares the speaker (or writer) the trouble of being specific. Lots of words function usefully as both nouns and verbs, and sometimes as other parts of speech as well. I used "light" as an example--there are many, many others, and I'd say "phone" is one of them. And I used "verb" as a verb as a joke. Kaye, like you, I'm annoyed by some nouns as verbs but not by others. I think the key is to be aware of what we're doing and to make careful choices. If we've got a good reason for using a noun as a verb, fine, but if an existing verb will express our meaning just as well or better, maybe we should stick to that. Why say someone referenced something when we can simply say he or she referred to it?

ReplyDeleteGreat column. Sometimes I lose track of all the changes going on in language. Thanks for this.

ReplyDeleteTerrie, I think we all lose track sometimes--the changes are so constant, and so often make so little sense. We all have to work at keeping ourselves aware of what's going on.

ReplyDeleteSome "verbing" produces a precise meaning in a more concise form, as with "access" v. "gain access to" or "text" vs. "type a text message and send it with one's phone." And I would defend "contact" precisely because it is vague; I use it in news articles followed by a phone number, an email address, and sometimes a website. It saves me from using three verbs or verb phrases. I see no reason for "efforting." I agree with your guidelines, Bonnie. Does it express a concept more precisely or concisely than existing verbs? One I hate: "conceptualize."

ReplyDeleteMo, I see your point about "contact. In that context, it does seem more concise than the alternatives. I don't have a problem with using nouns as verbs when it serves a useful purpose. I object only when speakers or writers do it because they're lazy or careless, or because they want to make something sound more impressive than it really is. "Efforting" strikes me as a prime example of that.

ReplyDeleteGreat article. I still refuse to use access as a verb though, as cumbersome as it may seem to some.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous, my husband agrees with you. (He also still refuses to use "update," while I've learned to live with it--I don't like it, but I can grudgingly admit to its usefulness.)

ReplyDelete