The forces of Evil have always been present in this strange country of Mexico, watered though it has been by the blood of saints.

Todd Downing

Vultures in the Sky

The “golden ages” of both mysteries and Mexico are pretty much behind us.

As to mysteries, diligent readers can still, at times, stumble onto the occasional forgotten trove of golden age “fair play” mysteries, where the plotting is stylish, the murders are relatively free of gore, and where all of the clues are handed to us yet we still reach the last page (or, perhaps, the penultimate page) befuddled. But today these are rare finds indeed. Agatha Christie remains in print, almost single handedly defying Professor Francis Nevin’s rule that the books die with the author. But most of the other golden age mystery volumes that once populated the library mystery shelves have, along with those authors, long since disappeared.

As to mysteries, diligent readers can still, at times, stumble onto the occasional forgotten trove of golden age “fair play” mysteries, where the plotting is stylish, the murders are relatively free of gore, and where all of the clues are handed to us yet we still reach the last page (or, perhaps, the penultimate page) befuddled. But today these are rare finds indeed. Agatha Christie remains in print, almost single handedly defying Professor Francis Nevin’s rule that the books die with the author. But most of the other golden age mystery volumes that once populated the library mystery shelves have, along with those authors, long since disappeared.

|

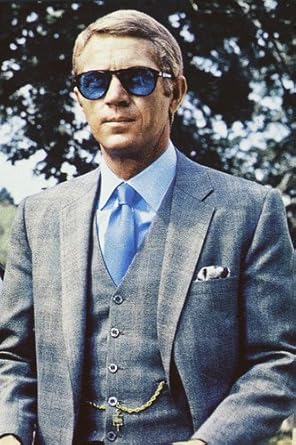

| Todd Downing pictured on the cover of Clues and Corpses by Curtis Evans |

Based on Curtis Evans’ Facebook recommendation I promptly ordered Downing’s Vultures in the Sky from Amazon. (An added bonus -- Vultures begins with a biographic sketch of Todd Downing written by Evans.)

Vultures is set on the Aztec Eagle, the Mexican train that for many decades provided daily rail service between Nuevo Laredo and Mexico City. The novel’s sense of claustrophobia and mounting terror is heightened by the constricted setting of the first class accomodation of the Aztec Eagle as it meanders its way along its 1,100 mile day-and-a-half journey from the Mexican border to the capital. Think of Vultures in the Sky as a sort of Mexican analog to Murder on the Orient Express. And from the moment I began reading I knew that I was on familiar ground.

Vultures is set on the Aztec Eagle, the Mexican train that for many decades provided daily rail service between Nuevo Laredo and Mexico City. The novel’s sense of claustrophobia and mounting terror is heightened by the constricted setting of the first class accomodation of the Aztec Eagle as it meanders its way along its 1,100 mile day-and-a-half journey from the Mexican border to the capital. Think of Vultures in the Sky as a sort of Mexican analog to Murder on the Orient Express. And from the moment I began reading I knew that I was on familiar ground.

So -- why did Vultures speak personally to me? Well, although I am still young enough (thankfully!) not to have experienced Todd Downing’s Mexico of the 1930s, I am very familiar with the Aztec Eagle. It is the same train that I rode, on my own, during the summers of 1967 and 1968 -- my 17th and 18th years. (What were my parents thinking? I would have locked my kids in their rooms if they had proposed undertaking such an unchaperoned adventure in their teens.)

|

| My (ancient!) copy of Mexico on 5 Dollars a Day |

My teenage adventures in Mexico were momentous for me in many respects; so much so that I could never bring myself to part with the guidebook that was my bible throughout my five weeks of riding the rails each of those summers -- Mexico on 5 Dollars a Day, by John Wilcock. Here, in words that could have been taken from Vultures in the Sky, is the description of the Aztec Eagle from pages 22 and 23 of the 1966 edition of 5 Dollars a Day:

The Mexican Railroad’s pride and joy is the glittering Aztec Eagle, which leaves the border town of Nuevo Laredo at 6:15 p.m. daily. Once you have boarded this and sat down to dinner, all kinds of exciting things happen. Take a look at the railroad company’s own brochure:

“During your trip south, from an easy chair in the lounge, you may watch the dramatic panorama of Mexico unfold. On either side of the train stretch desert plains studded with dwarf and giant cacti. Suddenly, as though spun round on a revolving stage, the landscape changes to tree-dotted valleys. The train passes the Tropic of Cancer. Inside the air-conditioned cars there is no indication that the train has entered tropic territory.

The train trip in itself is an introduction to Mexico -- to its rich agricultural areas, cacti-covered desert stretches, valleys and highlands. At times the train winds over giddy peaks, clings to sheer rock walls, looks down into steep ravines, crosses mineral-laden land, rushing mountain streams and great irrigated fields. Along the way there are small, typical Indian villages of adobe huts, processions of burros laden for market, Indian families dressed in regional clothes, serapes and rebozos. Whenever the train stops, they gather outside the cars offering for sale food, fruits, candy, drinks, bright woven basketry, serapes and other local handicrafts.”

|

| Typical Pullman Sleeper Car |

|

| Interior of typical Observation car |

|

| The observation car at the end of the Aztec Eagle |

Although The Aztec Eagle had staked its claim as flagship, a strong argument could be made for the proposition that that honor should at least be shared with the nightly train from Mexico City to Guadalajara. That train, all first class, was comprised of 18 Pullman sleepers, two diners, two club cars and two observation lounges. The train was so long that it left Mexico City’s Buena Vista station nightly in two sections, each propelled by its own set of engines. The trip itself was leisurely -- the train left at 8:20 each evening, and arrived in Guadalajara (under 300 miles to the north west) at 9:00 a.m. the next morning. Accommodations on the train sold out almost every trip -- prospective passengers had to reserve their tickets days in advance. The cost? According to Mexico on 5 Dollars a Day I paid around $6.00 to travel first class between Guadalajara and Mexico City.

It is a hard battle for any series of golden age mysteries to remain in publication (almost as hard as it has been for rail passenger service to survive). Mysteries run the risk of becoming dated, and the tastes of the reading public is apt to change. But that battle likely was a particularly difficult one for Todd Downing’s series, I suspect, since the series is set in the unfamiliar Mexico of his era. That Mexico has simply ceased to exist. That era, and the Mexican trains as well, are gone.

When I was a child, before I discovered Mexican rail transporation, my father’s favorite vacation was a driving trip from St. Louis, Missouri (our home) to Mexico City. Part of that drive was along Mexico’s Route 101, which stretches from Matamoros, Mexico (across the Rio Grande from Brownsville) to Ciudad Victoria. One should question our sanity in undertaking this 3,400 mile round trip in the constraints of a two week vacation back then, but there is no question at all as to the the lack of sanity of someone attempting a road trip through central Mexico today. And that is particularly the case along Route 101. The Washington Post has this to say about present conditions along that highway:

|

| Mexico Route 101 -- The Highway of Death |

Highway 101 through the border state of Tamaulipas is empty now — a spooky, forlorn, potentially perilous journey, where travelers join in self-defensive convoys and race down the four-lane road at 90 miles per hour, stopping for nothing, and nobody ever drives at night.

. . . .

As rumors spread that psychotic kidnappers were dragging passengers off buses and as authorities found mass graves piled with scores of bodies, people began calling this corridor “the highway of death” or “the devil’s road.”

For a fictionalized (but I suspect accurate) view of what traveling through central Mexico is like today, try Michael Gruber’s latest book, The Return, and compare the horrors depicted there with the Mexico that I knew and that is depicted in Vultures in the Sky. As The Washington Post also reported, even convoys traveling together down “the devil’s road” -- the stretch my family rolled along in our station wagon -- are not safe. Several years ago one such convoy failed to arrive in Ciudad Victoria. The charred bodies of 145 drivers and passengers were eventually found by the Mexican police in a desert fire pit. Even numbers did not buy safety, and facing a convoy meant nothing to the Mexican drug cartel.

I read these news reports of current Mexican horrors, I remember the Mexico that I traveled through as a child with my family, and that I later traveled through alone as a teenager, and I am bewildered and saddened by the change that 50 years has wrought.

I read these news reports of current Mexican horrors, I remember the Mexico that I traveled through as a child with my family, and that I later traveled through alone as a teenager, and I am bewildered and saddened by the change that 50 years has wrought.

The Aztec Eagle and the nightly train from Mexico City to Guadalajara, in any event, are long gone. Except for two tourist lines -- one servicing the Copper Canyon, another running to and from a popular tequila distillery -- all Mexican inter-city passenger service is currently a thing of the past. All of the other Mexican passenger trains were discontinued in 1995. We can't even blame the drug trade for this. The decision pre-dated much of Mexico’s current descent into warring drug cartels.

For several years I taught a graduate course for the University of Denver that traced the history of transportation regulation in the United States. The gentleman who taught the course immediately following mine was an official of Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México. While visiting with him once I asked him about Mexico’s 1995 decision to abandon its popular passenger rail service and his response was a simple one: The railroad realized it could make more profit running one full boxcar of cargo between Mexico City and Guadalajara than it could running that 50 car first class passenger service between those two cities.

One could, of course, question that logic. Rail passenger service is subsidized virtually everywhere, including in the United States. The need for the service is not, necessarily, susceptible to a strict profit and loss analysis. It also requires a balancing of public transportation needs. But all of that is a different issue for a different article. The point here is also a simple one: the Mexico that Todd Downing knew in the 1930s, and that I knew in the 1960s, including The Aztec Eagle, is no more. Segun dicen en español -- Ya se fue.

But, then again, nothing stands still. Where we are today is not, necessarily, where we will be tomorrow. And sometimes you might, if lucky, get to go home again. Or, for our purposes, perhaps back to Mexico.

|

| High Speed Rail: Still an Option for Mexico? |

And a renewed Mexican passenger rail system is also not beyond the realm of hope. The first fitful step -- and it would have been an enormous one -- has been the attempt by the Mexican government to build a high speed inter-city passenger rail system connecting the cities of Mexico. In 2014 Mexico entered into a contract with a Chinese consortium to construct such a line but, in light of budgetary problems and continuing governmental scandals, the project was put on indefinite hold this past February. When and if that services is finally begun it is estimated that the trip from Mexico City to Guadalajara (that 12 hours overnight trip that I took as a teenager) would then take just over two hours.

Two hours! That’s hardly enough time to settle into your seat with a highball and a good Todd Downing mystery.