"Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future."

-- Niels Hendrick David Bohrs, Danish physicist

|

| The (doctored) display from Doc's DeLorean |

As it turns out the Facebook post was a hoax – a photoshopped version of the DeLorean screen. In fact the actual date that Doc flew off to in the movie was October 21, 2015. But Devon’s larger disappointed point is still valid – unless we come up with flying cars in the next three years the movie’s view of the future turns out to be definitionally anachronistic.

Two weeks ago I wrote about Michael S. Hart, who had the prescience to foresee a world that would embrace e-literature long before the internet or the home computer existed. Hart’s foresight is all the more remarkable when one considers how poorly most of us perform in the prediction department.

A prime example of failing this challenge is the Stanley Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey. I remember seeing this movie for the first time in 1968 and being completely blown away. I think it was the only movie I saw that summer and I also think I saw it seven times. Viewed today the movie is . . . well, . . . dated. Twelve years after Y2K we are nowhere close to Kubrick’s vision of future space travel. In fact, we were closer in July of 1969, one year after the film premiered, when we were actually walking on the moon.

|

| On board the 2001 space station -- HoJo's sign at right |

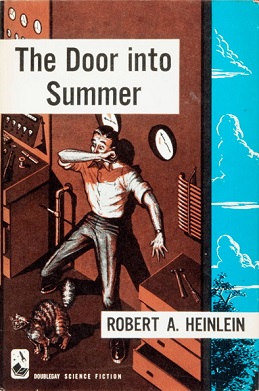

But to my mind just about the best examples of stumbling over the future are sprinkled throughout Robert Heinlein’s classic novel The Door into Summer. I need to note at the outset that Heinlein’s book, even with its predictive flaws, is one of my all time favorites and I re-visit it regularly. The Door into Summer was originally serialized in three issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in late 1956 and then published in hardcover in 1957.

But to my mind just about the best examples of stumbling over the future are sprinkled throughout Robert Heinlein’s classic novel The Door into Summer. I need to note at the outset that Heinlein’s book, even with its predictive flaws, is one of my all time favorites and I re-visit it regularly. The Door into Summer was originally serialized in three issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in late 1956 and then published in hardcover in 1957.The novel opens in 1970 and then jumps to 2000, giving Heinlein the opportunity to prophesize about not just one, but two different future eras and us the opportunity to shake our heads as to how wrong he got it since we have now lived through both. I read the novel for the first time in the 1960s, when I could still wonder at whether the author foresaw the 1970s and 2000s correctly. I then re-read the book again in the 1970s, when I was able to see how the 1970s predictions didn’t work out, while still holding out hope for the 2000s. Alas, I then re-read the novel most recently a few years ago. From those perspectives it has been interesting to watch, over the course of a lifetime, how the novel’s view of the future vectored from reality as I caught up in time with each era portrayed in the novel's timeline.

As I’ve said before, I don’t do “spoilers,” but there are still aspects of the novel that can be discussed without giving away too much. For example, the protagonist, Dan, is an inventor of robots -- “Hired Girl” (yeah, I know, even the name alone wouldn’t work now) and “Flexible Frank” -- which, in both 1970 and 2000 perform virtually all household chores. Never quite got there, did we? Those inventions and many other projections concerning life in both 1970 and 2000 that did not in fact come to pass provide an interesting, if unintended, subplot to this otherwise fine little story.

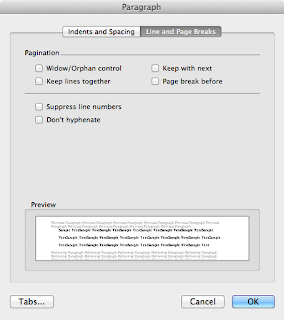

But my favorite Heinlein creation is Dan’s namesake invention: “Drafting Dan,” a machine that can automatically create engineering draft drawings. Drafting Dan creates these drawings using computer driven arms that draw on a drafting easel utilizing directions inputted from (gasp) a keyboard. The computer needed to power this invention has been shrunken to near room size by the use of super powerful new vacuum tubes.

|

| The earliest mouse! |

Like most predictions that go wrong, the blame can hardly be laid solely at Heinlein's feet. If anything has proven itself, it is the difficulty involved in figuring out what happens next. To envision the computer of the future Heinlein likely turned to those who in the 1940s and 1950s were at the forefront of the then-incipient computer industry – an industry that at the time involved figuring which of the spaghetti mess of multi-colored wires should be plugged in where.. Andrew Hamilton, a noted computer expert of the time, had the following to say in a 1949 article in Popular Mechanics hypothesizing on the future of computers: “Where a [computer] calculator . . . [in 1949] is equipped with 18,000 vacuum tubes and weighs 30 tons, computers in the future may have only 1,000 vacuum tubes and perhaps weigh only 1½ tons.” (“Hmmm,” we can almost hear Heinlein thinking.) In 1957, the year that The Door into Summer was published in hard cover, the editor of business books for Prentiss-Hall had this to say: “I have traveled the length and breadth of this country and talked with the best people, and I can assure you that data processing is a fad that won't last out the year.” At least Heinlein saw past naysayers such as this, and boldly chose a future where computers thrived. Other rejected paths include the prophecy of Ken Olsen, then chairman of DEC, who twenty years later, in 1977 “presciently” observed that “[t]here is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.” And printers and copiers? Here is IBM’s 1959 advice (to a team that later went on to found Xerox) concerning the future of the novel copying device the team was attempting to sell: “The world potential market for copying machines is 5,000 at most.”

Well enough of this picking on Heinlein. In fact, we are surrounded by prophetic mistakes that rear their humorous heads in literature. And they are not confined to technology. I have read a number of Randy Wayne White’s Doc Ford books, all set in Florida, and many dealing with Cuba. Five years ago, when the press was telling us that Castro lay dying and would not last the month, White apparently viewed that as gospel and took what looked to be a safe leap – he submitted a new installment in the series to his publisher in which Castro was already dead. Oops. White now has authored several additional books in the series over the last five years, each of which treks an alternate reality from ours, a world in which Castro has indeed already departed the mortal realm.

Well enough of this picking on Heinlein. In fact, we are surrounded by prophetic mistakes that rear their humorous heads in literature. And they are not confined to technology. I have read a number of Randy Wayne White’s Doc Ford books, all set in Florida, and many dealing with Cuba. Five years ago, when the press was telling us that Castro lay dying and would not last the month, White apparently viewed that as gospel and took what looked to be a safe leap – he submitted a new installment in the series to his publisher in which Castro was already dead. Oops. White now has authored several additional books in the series over the last five years, each of which treks an alternate reality from ours, a world in which Castro has indeed already departed the mortal realm. And, as illustrated by the computer quotes above, prognostication errors are not relegated solely to written fiction. They spring up all around us. Here is one of my favorites: During the Civil War it is reported that the last words of General John Sedgwick as he looked out over a parapet toward the enemy lines during the battle of Spotsylvania Court House were the following: “They couldn't hit an elephant at this dist . . . .”