If the situation between us were put into a book, it would be damned as utterly incredible

Letter dated May 12, 1949

Quoted in Blood Relations by Joseph Goodrich

It is a rare event for Ellery Queen fans to have a new publication to enjoy, While Queen novels continue to be published around the world – notably in Japan, Italy and Russia – Ellery’s adventures, and other Queen-related works, can be found in the United States virtually only in used bookstores. On line you will be searching ABE, not Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

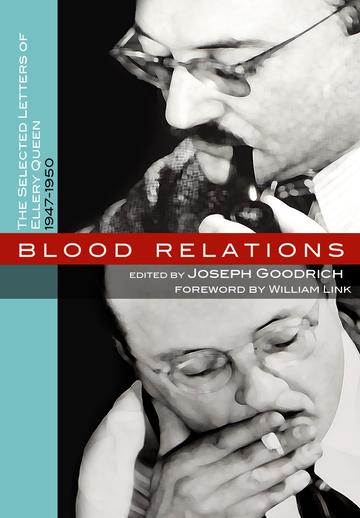

Swimming against that current, however, Joseph Goodrich has just offered up Blood Relations, the Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950, a slim but thoroughly engaging volume collecting the letters exchanged by Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee during the plotting and writing of three Ellery Queen mysteries – Ten Days Wonder, Cat of Many Tails and The Origin of Evil.

Swimming against that current, however, Joseph Goodrich has just offered up Blood Relations, the Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950, a slim but thoroughly engaging volume collecting the letters exchanged by Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee during the plotting and writing of three Ellery Queen mysteries – Ten Days Wonder, Cat of Many Tails and The Origin of Evil.The book is a great read on at least three levels: first, it provides a fascinating background on the writing of three of the strongest Ellery Queen mysteries, second it is a great teaching exercise on how mysteries are plotted, including how the suspicions of the reader can be deflected away from the true culprit, and third it is a revealing, and often troubling, insight into the rivalries that festered between two cousins, Dannay and Lee, who collectively were Ellery Queen.

Throughout their long literary partnership Dannay and Lee were famously at each others' throats. Lee described the partnership as a “marriage made in hell.” The friction in the “marriage,” as well as its long-term survival, was borne of necessity -- each cousin depended on Queen for the economic livelihoods of their respective families. And Ellery's survival could only be assured if the partnership between Dannay and Lee continued.

As mystery writer, professor and Queen scholar Francis M. Nevins has noted, neither Dannay nor Lee could complete a work of fiction alone. Rather, each of the Queen novels and short stories followed the same pattern: Frederic Dannay would supply a detailed outline of a proposed book or story – often running to 75 to 80 pages for a novel that would eventually ring in at around 300 printed pages. Then it would be left to Manfred Lee to transform the outline into a complete novel, building believable characters and a compelling narrative flow. According to Nevins, Lee could not plot out a story to save his life, and Dannay was equally incapable of writing a narrative from an outline. And so, bound at the wrists, and each damned by a resentment fueled by that which only the other could do, the cousins fought their way through over 40 Ellery Queen books.

Much of this acrimonious writing process was completed through the exchange of letters, particularly in the late 1940s when Lee was on the west coast supervising the production of the Ellery Queen radio show and Dannay was on the east coast editing EQMM. At a time when long distance telephone calls were unreliable and exorbitant, the cousins plotted (and bickered) in exchanges of very long special delivery letters. It is these letters that comprise Blood Relations.

The book reads as compellingly as good fiction, and offers up a fascinating insight into the minds of Dannay and Lee. A spoiler alert is warranted, however. Anyone reading Blood Relations will come away knowing all there is to know about Ten Days Wonder, Cat of Many Tails and The Origin of Evil.

The bitter and accusatory tone of the letters that comprise Blood Relations is not a complete surprise to Queen fans. Frederic Dannay’s papers, which contained copies of most correspondence between the cousins, were donated to the Columbia University Butler Library in 2005, the centennial year for Dannay and Lee, and therefore Ellery, as well. At that time Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine held a centennial Queen symposium at Columbia and Francis Nevins delivered a keynote lecture taken completely from the letters exchanged between the two cousins. But while the angry exchanges quoted by Nevins during that speech left a lot of the audience wide-eyed in 2005, reading the text of these exchanges in full provides even more of an eye opener.

|

| Francis M. Nevins at the Centenial |

The following exasperated passage from a 1948 letter from Lee illustrates this. Dannay has asked for a change of one sentence in Ten Days Wonder. Lee responds as follows:

When pages are spent arguing over one sentence in a draft, the reader is left to ponder how the finished products were ever produced. As Lee notes in a subsequent 1948 letter, “[w]hat began as friendly competition wound up as active and bitter hostility . . . our history as a ‘team’ is a series of explosions.” The marvel is that even given this the cousins in fact produced over 40 novels, anthologies and critiques.You say [that the phrase] is “out of key,” “ineffective,” and “tends to spoil the very good stuff that surrounds it.” I’ve reread the line in context and I don’t agree. I could take the line out to please you, certainly; but this very minor, unimportant example – by admission on both our parts – raises a major, important question: Is pleasing you, in the face of my strong affirmative opinion that the line is in key, effective and helps the stuff that surrounds it, to be my rule-of-thumb? We divided ourselves into rigid-boundaried “zones” just because our differences of opinion on basic matters of both plot and writing were so strong that we found it impossible to reconcile them either in principle or in practice. In the face of this, pleasing each other is pointless. We can only do, in our respective provinces, what pleases ourselves. . . .

On at least one level reading Blood Relations is therefore a bit like watching a rather steamy soap opera. The reader becomes enthralled, almost against better judgment, by angry tirades that normally would take place only behind closed doors. In that sense the experience of reading the book is a little akin to the natural tendency to slow down, even when we do not mean to, as we drive past a grisly automobile pile-up. Dannay and Lee mercilessly pick at each other, neither wanting to give an inch on a point, until the result becomes unbearable to both. And they do it all before our eyes. This from Lee, again in 1948 and addressing the drafting of Cat of Many Tails:

I now have the mere job of finishing this story. What in the good God’s world is the use of anything? What, I ask you? Why am I writing to you? Why do you write to me? We are two howling maniacs in a single cell, trying to tear each other to pieces. Each suspects the other of the most horrible crimes. Each examines each word of the other’s under a lens, looking, looking, looking for the worst possible construction. We ought never to write a word to each other. We ought never to speak. I ought to take what you give me in silence, and you ought to take what I give you in silence, and spit our galls out in the privacy of our cans until someday, mercifully, we both drop dead and end the agony.

The quotes provided here are but the tip of the iceberg that is Blood Relations. But the book also offers lessons on other planes. Beyond the vituperations that erupt in many of the letters of Dannay and Lee one finds two headstrong writers, each working to make the final product believable. Every writer already knows that despite what we may say, we do not particularly enjoy criticism. Strong criticism makes for a better final product, but each of us carries that silent wish that those who read our works will say “Perfect. Wouldn’t change a thing.” What Dannay and Lee subjected themselves to was just about the most rigorous barrage of literary criticism imaginable. Every single thing was subject to debate. But beyond the pent up hostility they each harbored, their arguments always have the purpose of furthering the written product. And the differences of approach that were at the core of each man fueled debates during the writing of the Queen novels that are illustrative of the struggles that all good writers go through, although more normally not in dialogue, when a book or story is devised and then executed.

The nature and end result of the process that brought about the Queen oeuvre is summarized by Dannay, also from a 1948 letter. Dannay's observations offer a denouement finally concluding the cousins’ blistering special delivery exchanges concerning Cat of Many Tails:

|

| Manfred B. Lee and Frederic Dannay |

[A]s I sit in front of the typewriter this morning, I feel extraordinarily calm; and in the calmness I see clearly – [even] without having read your [most recent] letter – that surely the answer is very simple: I must have misunderstood you, and you must have misunderstood me, and we both keep misunderstanding each other – and probably will keep right on. And perhaps that really isn’t too bad a thing, wearing as it is on our nerves and lives; it keeps both of us doing the best we possibly can, and while we are eternally suspicious of each other, and eternally hypersensitive to each other, the resultant work – coming out the hard way – is strangely enough, the better for it . . . [even though] the price is high . . . .Blood Relations is available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble. It is a must read for Ellery Queen fans, and it should also be a must read for writers interested in the meticulous plotting and drafting of mysteries.

Dale, this was absolutely fascinating! I’ve got to read this. Thanks!

ReplyDelete--Dixon

Interesting!

ReplyDeleteFlee all forms of literary collaboration is, I guess, the message.

Dale, another short story author and I tried a collaboration years ago We both liked the same type of stories, the same authors and enjoyed each other's published works. So, we wrote a mystery short together. And, while the relationship never became acrimonious, in the end we did not agree on the detective's name, appearance, height or even the story title. We did agree to split the money, 50 - 50, however, the small press magazine which accepted the story folded before publication. I'm amazed at how successful collaborations do it.

ReplyDeleteAs the record reflects, I have collaborated as well, and it is a challenge. The intriguing thing about Dannay and Lee, however, is, as the book illustrates, neither could have produced a book alone. The two ended up parasites, feeding on each other. And when Lee died, in 1971, the stories stopped.

ReplyDeleteI've always thought a successful collaboration was a rare and precious gift. I've just completed what might be my only experience of one: 400 hours in the studio with the co-producer of my CD of original songs. Note that it wasn't a writing collaboration--I think I'd hate that, even if I sometimes wish I had it. But the Queen story turns my idea of "successful" on its head. There's no denying the outcome of the Queen collaboration was successful. But the process sounds like a nightmare.

ReplyDeleteAn excellent review of a book that really blew me away when I read it. It's worth noting that the letters - full of accusations and recriminations - are still loaded as well with personal concerns about the other's family. "Dear Dan" and "Dear Man" indeed - talk about dysfunctional! It's a harrowing read, in many ways - and, because there are spoilers everywhere, should not be read until the reader has read "Ten Days Wonder," "Cat of Many Tails" and "The Origin of Evil." You might enjoy my review at Classic Mysteries.

ReplyDeleteI agree with R.T.--I'm amazed that collaborations ever work. I've tried it only once--a Boston mystery writer and I co-wrote a story a few years ago that we then submitted to AHMM. We both had a lot of fun with the story, but I think we received the fastest rejection in history.

ReplyDeleteI heard somewhere that collaboration is "twice the work for half the pay."

But back to what I really wanted to say: I will certainly read Blood Relations, Dale. Thanks for telling us about it.