In mystery stories, the crime story typically ends with the detective's dénouement explaining how he arrived at his conclusions. In some of the 1940s radio plays, the protagonist might even chortle: "Old Sparky will electrify you, Eli!" or "It's the gallows for you, Gusman!"

In real life, this can be the point when the plot intensifies if it's believed detectives or the prosecutor got it wrong. And, in a surprising number of cases, they do. Common wisdom argues a tiny fraction are mistaken, but common wisdom is wrong. Looking only at DNA cases, the State of Illinois discovered one in sixteen condemned men were innocent, but cases of actual innocence could be double that. Experts extrapolate that as many as one in eight men sent to their deaths may be innocent. If they're right, three hundred currently on death row might not be guilty.

That number may be extremely conservative because the Innocence Project exonerated 250 men by February of last year. The pace is slowing… in many cases there is no DNA to connect the crime with the accused but, according to Innocence Project statistics, eyewitness identification erred in an astonishing 70% of their cases. Even in up-close-and-personal rape, identification is often wrong.

The Court of Lost Appeal

Another reason the pace is slowing is that prosecutors and courts throw up impediments to testing. Prosecutors sometimes 'lose' evidence or launch legal arguments to prevent testing.

In Kafkaesque rulings two years ago, the Supreme Court slapped down the Innocence Project. They held that prisoners have no right to post-conviction DNA testing. The Supreme Court expressed deep disdain when DNA was used to exonerate. In dismissing exculpatory DNA evidence, one of the justices wrote that forensic science has "serious deficiencies". Chief Justice Roberts expressed a fear that post-conviction DNA testing risks "unnecessarily overthrowing the established system of criminal justice."

Finality

In middle school, we're taught the accused are considered innocent until adjudged guilty. This remains true even though the prosecution comes to court with several advantages and the defense is often, well, defensive.

To this Court, 'finality'– the court's term for closure– is more important than accuracy. As law professor General Beishline said, "If you've come to the law seeking justice, you've come to the wrong church."

The AEDPA, Gingrinch legislation signed into law by President Clinton, prohibits federal courts from remedying miscarriages of justice. The AEDPA rendered federal courts powerless to correct state courts' misinterpretations of U.S. constitutional and federal law. Judges may try to step outside legalities to set matters to right, but few judges are willing to risk their careers. They are, after all, subject to elections and reappointments.

|

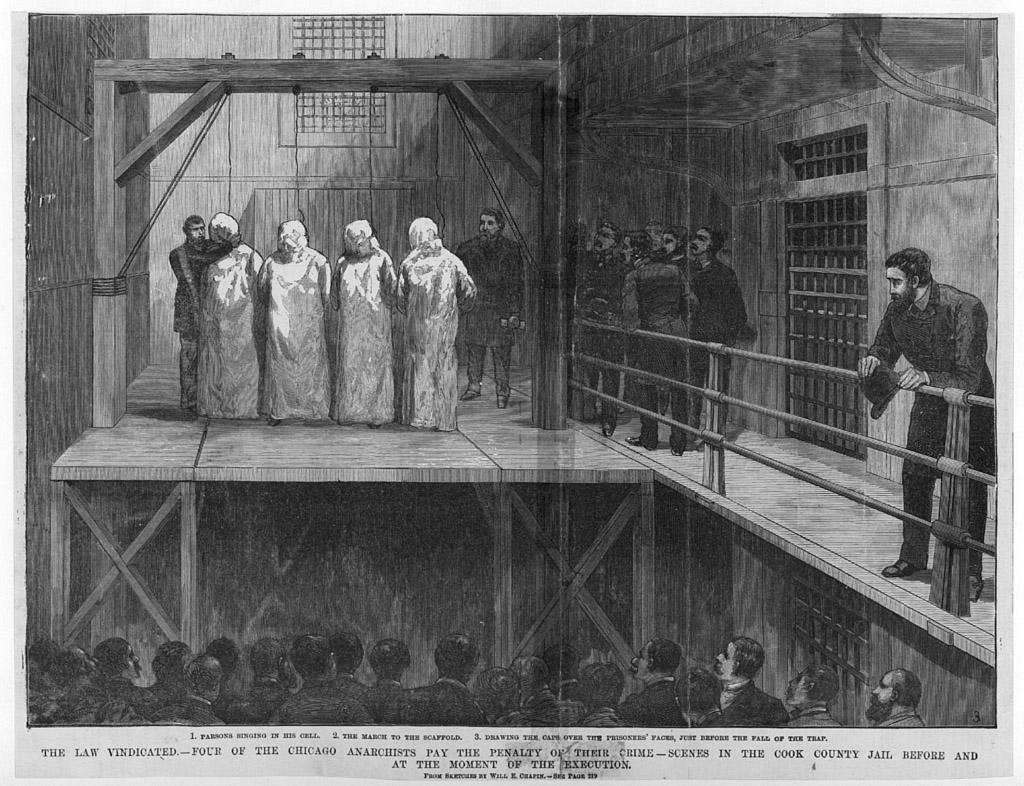

| Execution of 'Anarchists', Chicago, 1887 (credit: ChicagoHistory.org) |

Savvy and Savaging Politics

Arkansas: Capital punishment makes good politics. During his first presidential campaign, Governor Bill Clinton returned to Little Rock to sign the death warrant of a mentally deficient man (who was saving his pecan pie until after his execution). Clinton may have had in mind the lessons of another governor, Michael Dukakis who'd cleared the way for Willie Horton to be freed.

Florida: Our Florida governor Bob Martinez started signing death warrants his first full day in office as quickly as they were slapped on his desk. When it appeared he would lose re-election, he ramped up executions against international protests. Several legal experts are convinced he wittingly executed innocent men. As the Innocent Project demonstrated significant numbers of the condemned were truly innocent, Florida (like North Carolina's Inquiry Commission) recently established a commission to review doubtful cases.

Texas: The last two governors of Texas who campaigned for president set records in numbers of executions. Both Governor Bush and Governor Perry asserted Texas never wrongfully executed anyone, ever. Governor Perry was so convinced, he shut down a state investigation by the somewhat gutless Texas Forensic Science Commission that was looking into doubtful convictions. As writer J.D. Bell said, "If Perry was certain of Texas' infallibility in assuring the guilt of all 235 men sent to death during his gubernatorial reign, then there surely would be no reason to block a thorough investigation into Willingham's execution."

Illinois: Governor George Ryan has had his woes, but his legacy may have helped reshape capital punishment in the land of Lincoln. Once freed from political constraints, he turned his attention to the nearly 300 men on death row. In a matter of months, 18 were exonerated, not merely judged not guilty but proved not guilty.

Two Wrongs

Almost as bad as executing the wrong man, the real perpetrator likely goes free. In the recent Troy Davis case, after seven witnesses recanted their stories, the remaining chief accuser against Davis was the most likely suspect. Calls for relief from conservatives and liberals, from religious and political leaders went unheeded. Psychologists contend his repeated trips to the execution chamber were a form of torture.

When witnesses recant, appeals courts and parole boards almost invariably take the position witnesses lie the second time. Though convenient for the prosecution, that psychology seems backwards to me. Transcripts coming out of parole hearings show boards strongly influenced by prosecution bias and seldom by the notion that a jury erred. Indeed, the last judge who looked over Troy Davis' new evidence and witness recantations agreed there was some little mitigation, but in the end wrote Davis failed to prove his absolute innocence and that repudiations were "smoke and mirrors."

Make a Write

The English teacher in my tiny high school formed debate teams. I'm grateful to Miss Arthur's debates for a couple of reasons. First, I'm still amazed how often the fallacies taught in debate show up unchallenged on talk radio. Secondly, the exigencies of preparation forced me to thoroughly research the death penalty. For a multitude of reasons– ethical, technical, financial, and moral– I came away convinced capital punishment was wrong.

But mine isn't the final opinion— it is only mine. Yours may differ and feel welcome to talk about it here.

(We're still hearing some are having trouble posting comments even after following the guidelines above right. Try other 'profile' options to get that comment to us.)

Leigh, very interesting! What a shame that some comments aren't getting through. Let's see if this makes it. I'm using name/URL and I'm on Safari.

ReplyDeleteHi Fran! Fortunately you're making it through. I wish Blogger had an easier reporting method for those who aren't.

ReplyDelete>… legislation signed into law… prohibits federal courts from remedying miscarriages of justice.

ReplyDeleteProhibits? They make it illegal to correct errors? Here is the true injustice. (shaking head)

[I, too, use the Name/URL option for commenting (sans URL) and have not experienced any problems.

ReplyDeleteWhilst on the subject of things technical, is there any way we ordinary mortals can format comments - bold, italic, insert hyperlinks, etc?

BTW: That first image is chillingly appropriate.]

Unaware (but hopefully not uncaring), the populace had a sense that condemned criminals were somehow getting away with murder when appeals dragged on. Soundbites included keywords like 'closure' and 'finality', with the sense that somebody needs to pay.

ReplyDeleteThere's also a belief that prisoners lead a cushy life with color televisions, free food and medical care, and guards who cater to their every whim. The public is shielded from the beatings, rape, murders, lack of educational materials, and sometimes inedible food… or else they think prisoners deserve the additional punishment. There are sheriffs who feed prisoners stale bread and moldy bologna because their department gets to keep every penny saved from a prisoner's $1.13 (or whatever) meal allocation. One popular sheriff brags he feeds his dogs better than his prisoners. Here, the Orange County Sheriff removed the rooftop basketball court because drivers on I-4 thought prisoners spent all day playing sports.

We love tough talk and tough action but the problem is that our justice system has now geared itself toward all out punishment with little or no thought to rehabilitation. What happens when a prisoner gets out who spent the past 10 years shoveling dirt? He can't find a job but he has to eat, so…

Congress pandered to the people with the AEDPA law, which promised speedy processing… at the expense of justice. Congress largely tied the hands of appeals judges to render sensible judgments.

Parole boards are no longer independent but have become tools of politicians. Normally state governors appoint parole board members with kind of a tacit mandate: Don't do anything to embarrass the governor; i.e, don't release anybody who might rape, murder, pillage again. Naturally, the safest thing is to not release anybody.

Parole boards automatically assume a person's in prison because they're guilty. That may be true 90% of the time, but that means 10% are (most likely) innocent. Parole boards are more likely to respond to an actually murder who says "Yeah, I shot the guy, I'm sorry, I got religion, and I learned my lesson," than an innocent prisoner who stubbornly insists "I didn't do it." Thus the concepts of clemency, compassion, and charity have become largely meaningless.

The US locks up a greater percentage of its population than any other Western country and most third world nations, and we lock them up longer, a condition called 'over-sentencing'. It's not only counterproductive, it's frightfully expensive, but taxpayers have shown great willingness to support a subculture of incarceration.

And execution.

Good question, ABA. You can format the simpler (and safer) HTML codes like <b>bold</b>, <i>italics</i>, and <a href="http://about.me/Velma">links</a>.

ReplyDeleteA while back we had a lawyer who works with the Innocence Project and an exonerated man, one of its successes, as speakers at an MWA meeting. It was chilling and compelling. He'd spent 25 years in prison on the testimony of a crooked cop, if I remember correctly.

ReplyDelete"and the defense is often, well, defensive." Having sat in on numerous trials, I found some defenses to often be...well, offensive. Our judicial system is deficient on both sides. Refusal to admit evidence that might be prejudicial against the defendant because he/she shouldn't have to see, along with the jurors, the results of his/her violence. No, I don't want innocent people convicted, but I think our system needs "fixing" also for the evidentiary rules/laws that protect the guilty from being convicted.

ReplyDeleteAnon, you're right. One example of an offensive defense happened at the Casey Anthony trial here in Orlando. I thought the accusations made againt George Anthony were disgusting, but José Baez accomplished what he set out to do– savage the parents' reputation to save his client. Baez hinted (and evidence suggested) Casey was guilty of something.

ReplyDeleteAfter the trial, some local call-in radio shows demanded disbandment of the jury system. In this case, the jury shouldn't be blamed. Overcharged with first degree murder, Orange County prosecutors opted for all (death) or nothing. Attorneys for both sides clearly didn't fathom the computer evidence and much of the forensic evidence hinted more as much toward an accident gone horribly wrong as it did murder. Even if the jury believed Casey was only guilty of child neglect, she was still eligible for the death penalty, which I believe influenced the verdict.

Yes, defense lawyers can be offensive!

Having set in on several state and federal trials, and having second chaired several of my own cases, let me say that the competency and/or leanings of the judge, the prosecutor, the defense attorney, members of the jury, testifying witnesses and the evidence allowed to be presented, definitely affects the outcome of a trial, sometimes regardless of the truth. I'm not sure how to control the human element in the system, nor the econamics part. A rich person can probably hire a top attorney, while the poor are assigned a public defender who may be overworked and possibly not as talented as the top defense lawyer. Inequities do exist within the system, yet it is better than a lot of countries have. We just need to keep working on it to better the process for all.

ReplyDeleteWell said, RT. A government litigator once told me the deepest pocket wins.

ReplyDeleteI don't imagine any country has a judicial system free of problems. Iran comes first to mind, but Italy sounds incredibly screwed up. The Amanda Knox trial is only the most recent of a number of questionable trials there.

I have a Google account, and once I select my account, I have no problem posting comments.

ReplyDeleteI think judges and prosecutors often refuse to accept evidence showing an individual may be innocent because, like many of us, they do not want to be proven wrong. They may feel if they are proven wrong, then the system is flawed, which, of course, it is.

I was attending my class reunion last week, so, I’ve been catching up on the articles today.

I think you make some excellent points, Leigh. Clearly there are problems with the justice system, which need to be addressed—first among them: better-protecting innocent people from being punished by the legal system.

ReplyDeleteOn the flip-side, there’s the example of Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt. The two men, both serving sentences for murder, escaped from a Florence, AZ prison in 1978 with the assistance of two of Tison’s sons. Over the subsequent (roughly) twelve days, the group murdered a 24-year-old marine, his wife, their 22-month-old son, and teenage niece (The family had stopped to lend assistance, because the Tison’s car had broken down.)—as well as another couple on their honeymoon.

In a case like this, I think justice would have been far better served by executing Tison and Greenawalt (Tison had originally been sentenced for murdering a prison guard, and Greenawalt for the murder of a sleeping truck driver.), before they killed another six people.

The problem, of course, is differentiating between the guilty and the not-guilty—100% of the time. Unfortunately, that’s something I think is probably beyond the human capacity.

But, it sure would be nice if somebody invented a time machine. Then we could prevent the deaths of six innocent people, and return 20+ years of life-time to a person sentenced for a crime s/he didn’t commit.

Dixon, I've also thought a time machine would be handy for both current and historical crimes. In a way, I suppose city fathers (and mothers) are getting around the time machine problem with the proliferation of municipal cameras recording every move and nuance. We hardcase civil libertarians never find easy answers.

ReplyDelete