Last week I received an eagerly-awaited package in the mail -- my author’s copies of the December, 2013 issue of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. SleuthSayers is well represented with two stories – one by David Dean and the other (I admit that this is the one for which I was waiting) by me.

An organized approach to writing fair play mysteries dates at least from the 1930s when a number of famous (or soon to be famous) British mystery writers, including Christy, Sayers and Chesterton, to name but three, established the Detection Club with the intention of establishing standards for “fair play” detective stories. Each of the members of the club took the following oath, reportedly still administered today:

In the 1930s an English writer, Dennis Yates Wheatley, was famous for his series of mystery and occult novels. Extraordinarily prolific, Wheatley also authored the Gregory Sallust espionage series that many credit as the inspiration for Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. Searching for a clever way to present fair play whodunits Wheatley teamed with a fellow wine aficionado, art historian James Gluckstein Links, and produced a series of fair play mysteries that the team referred to as “Mystery Dossiers.” The dossiers featured mysteries constructed by Links and then written by Wheatley. The first of these, Murder off Miami, was published in 1936 and quickly sold 120,000 copies. It was followed by Who Killed Robert Prentice, (1937), The Malinsay Massacre, (1938) and Herewith, the Clues, (1939). The dossiers were mysteries of a different ilk -- while they contained narratives setting forth the underlying story, they also gave the reader a lot more.

Accompanying each mystery was a series of clues -- real clues, such as entire newspaper articles, burnt matches, strands of hair, an arsenic pill (from which, the dossier explained, the poison had been removed). And in each case the solution to the mystery was contained, at the end, in a sealed envelope. The game, then, was for the reader to examine the clues along with the narrating detective as the story progressed; the approach allowed the reader to see precisely what the detective sees, that is, the wheat along with the chaff.

Night Film, to be clear at the outset, is a mystery, but not a classic fair play mystery. What it is is a really fine book. It grabs the reader, holds the reader’s attention, and then deposits the reader, at the end, a slightly different person. The narrative is so compelling at times that the reader may even begin to perceive the world differently -- I know that I did -- simply as a result of having read the story.

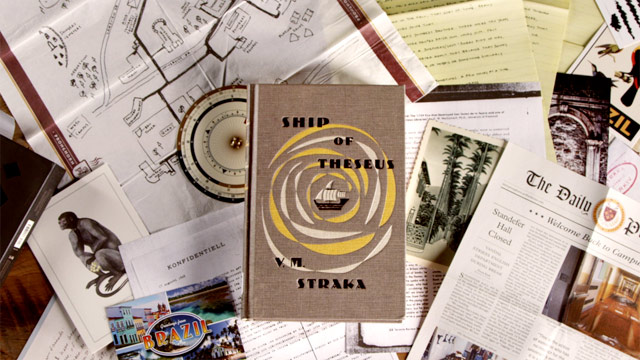

But Night Film also employs a startling gimmick -- when evidence appears in a magazine story the narrative stops and the magazine takes its place. The same is true of police reports, college newspapers, slips of paper, a CD album cover -- all are reproduced between the covers of the book. And not content with this, the book goes further -- if you read it equipped with a smartphone loaded with the Night Film app (free for the downloading) additional content appears on your phone when various pages of the story are scanned. The result is a near complete immersion into the world created by Pessl.

You probably get the idea that I think Night Film is a sensational read. As I have said many times, I am loath to dish out spoilers in a review. So, beyond what I have said already, you will just have to take my word for it!

Like the previous stories I have been fortunate enough to place in the pages of EQMM, my latest story, Literally Dead, is an Ellery Queen pastiche. Since it is written, as close as I can make it, to the style of Ellery it is a “fair play” mystery -- that is, all the clues are there, but are hopefully presented cleverly. Sleight of hand is at the heart of all golden age fair play mysteries. While interest in this genre may have waned somewhat in recent times, mysteries premised on obscure but solvable puzzles have been with us a long time, at least since the days of Poe and Doyle. But the genre really hit its stride in the middle of the twentieth century.

|

| a Detection Club dinner |

Do your promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?The members of the Detection Club went on to establish rules of fair play that, by and large, have governed the writing of fair play detective stories ever since. The most important of those rules is that every clue necessary to solve the mystery must be revealed, in advance, to the reader.

The task of actually revealing all of those clues in advance can be a thorny one. After all, one cannot do it in too obvious of a way. Often, describing a clue in a manner that conveys its full importance to the reader can amount to revealing too much, a too-easy tip to the ultimate solution. Moreover, some clues are simply difficult to describe in narration. The description may bog down if embodied in the detective’s first person narrative or the third person narrative of the author, or the clue itself may be difficult to "show" to the reader. As an example, a typewriter may have telltale discrepancies, such as cuts in some letters, that will allow the detective to tie a message to a specific machine. But how do you fairly show this in the context of a narrative? Or another example -- how do you show one important aspect of a newspaper article -- do you highlight it by presenting it alone, or do you risk boring the reader by presenting the entire article, none of the rest of which is relevant?

There is a simple solution to all of this, although the solution requires a degree of author control that is unavailable in most publishing venues. But the solution is still there -- if the author has the means, he or she can simply include all of the clues in their entirety along with the narrative. Like most simple solutions this one is not at all simple to put into practice. But it has, nevertheless, been tried. It’s interesting to take a look at two different attempts, separated by about 75 years.

|

| Dennis Yates Wheatley |

Accompanying each mystery was a series of clues -- real clues, such as entire newspaper articles, burnt matches, strands of hair, an arsenic pill (from which, the dossier explained, the poison had been removed). And in each case the solution to the mystery was contained, at the end, in a sealed envelope. The game, then, was for the reader to examine the clues along with the narrating detective as the story progressed; the approach allowed the reader to see precisely what the detective sees, that is, the wheat along with the chaff.

The approach intrigued the reading public, but, as can be imagined, the production costs for these mysteries were inordinately high. It is reported that hair samples required by one of the dossiers were secured from European nuns. Matches were burned seriatim by employees of the publisher for inclusion in one of the dossiers. And many of the clues had to be wrapped in wax paper, and then affixed by hand with staples to the appropriate page in the final volume. Little wonder that pristine copies of the original dossiers -- with the clues still encased, and with the ending still sealed in that envelope, sell for many hundreds of dollars.

The Wheatley/Links works were re-issued in the late 1970s by Hutchison and Company Publishers in London, but even with modern technological advances the cost of publication inspired few imitators.

Between the 1970s and today advances in computer technology and computer gaming saw similar attempts to offer up not only the story but the clues -- several computer simulation games based on Sherlock Holmes stories accomplished this with varying degrees of success. But, at least to my knowledge, a full-blown attempt to harness these technological advances in the context of published literature was not attempted. Until this August, that is, when Random House published Marisha Pessl’s brilliant (there. I’ve said it) new occult thriller and mystery Night Film.

|

| Marisha Pessl and her great new book |

But Night Film also employs a startling gimmick -- when evidence appears in a magazine story the narrative stops and the magazine takes its place. The same is true of police reports, college newspapers, slips of paper, a CD album cover -- all are reproduced between the covers of the book. And not content with this, the book goes further -- if you read it equipped with a smartphone loaded with the Night Film app (free for the downloading) additional content appears on your phone when various pages of the story are scanned. The result is a near complete immersion into the world created by Pessl.

The Links and Wheatley mystery dossiers of the 1930s similarly wrapped the reader into the narrative, but were often criticized as being too much gimmick and too little story. That cannot be said of Night Film, which is a near perfect blend and weighs in at over 600 pages of mesmerizing story. The addition of forays into the actual evidence only serves to heighten the reader’s involvement.

You probably get the idea that I think Night Film is a sensational read. As I have said many times, I am loath to dish out spoilers in a review. So, beyond what I have said already, you will just have to take my word for it!

Oh, yeah. And when you buy it at a bookstore, or download it for your e-reader, why don’t you also pick up a copy of the December issue of EQMM!

.jpg)